- TADASHI HATTORI’s resolve to become a doctor sympathetic to the patients and their families happened when he was fifteen, after seeing his cancer-stricken father so rudely treated when he was admitted to the hospital.

- After seeing firsthand the prevalence of cataract blindness, dire lack of eye specialists and up-to-date treatment facilities in Hanoi, Vietnam, HATTORI set off on a life of shuttling between Japan and Vietnam almost every month.

- To date, Hattori and his team of Vietnamese doctors have treated more than 20,000 patients. He has trained more than thirty Vietnamese doctors who can now perform sophisticated eye operations, and he has donated or facilitated the donation of medical equipment to local hospitals.

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes his simple humanity and extraordinary generosity as a person and a professional; his skill and compassion in restoring the gift of sight to tens of thousands of people not his own; and the inspiration he has given, by his shining example, that one person can make a difference in helping kindness flourish in the world.

Stories of otherwise ordinary individuals who, moved by the spirit of pure generosity, can transform the lives of so many, make us feel good and hopeful about the world.

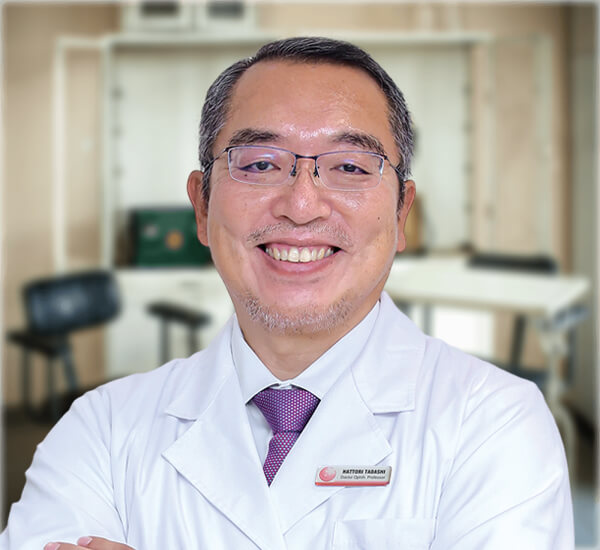

This is the story of fifty-eight-year-old Japanese ophthalmologist TADASHI HATTORI. Born in Osaka in 1964, he graduated from Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine in 1993 and then went to work in hospitals in Japan. Asked why he wanted to be a doctor, he said that he had resolved to become one when he was fifteen, after seeing his cancer-stricken father so rudely treated when he was admitted to the hospital. He wanted to become a doctor sensitive to the feelings of patients and their families. In 2002, he visited Hanoi for the first time at the invitation of a Vietnamese doctor and found that in a country where cataract blindness was prevalent, there was a dire lack of eye specialists and up-to-date treatment facilities, such that it was common for people in rural areas to go blind because they did not have access to needed care or could not afford the cost. He was deeply moved. And what started out as a visit became a life mission. When he returned to Japan, he used his savings to buy medical equipment to donate and went back to Hanoi. This set him off on a life of shuttling between Japan and Vietnam almost every month, spending a total of 180 days in Vietnam—giving free eye treatments; training Vietnamese doctors; donating equipment and supplies to hospitals—and then the rest of the year in Japan, working in hospitals to raise an income for his family and mission.

Explaining his passion to help, he says: “Whether people can see or not decisively affects their lives. Even just healing one eye may make it possible for someone to attend a school or go back to work. It can give relief to family members who have been looking after an affected person. I can’t turn my back on people who are on the verge of losing their sight just because they lack the money to pay for treatment. My starting point as a doctor is to help people.” Perhaps remembering his father, Hattori says, “A doctor should have not only the skills but also the heart. That’s why my motto is, ‘Treat your patients as your parents’.”

To date, HATTORI and his team of Vietnamese doctors have treated more than 20,000 patients. Driven, HATTORI would perform forty to fifty cataract operations or six to eight vitrectomies per day. He has trained more than thirty Vietnamese doctors who can now perform sophisticated eye operations, and he has donated or facilitated the donation of medical equipment to local hospitals. Cognizant that the need is greatest in the rural areas, he has led medical missions with a team of Vietnamese doctors, giving free treatments and performing surgeries for thousands of people.

To support and upscale his work, HATTORI founded the Asia-Pacific Prevention of Blindness Association (APBA) in 2005, with him as executive director, to enlist participation in training doctors, helping hospitals, and conducting free treatment and surgeries. In 2014, with investors and medical colleagues, he founded the Japan International Eye Hospital in Hanoi, one at par with Japan’s top ophthalmic hospitals, to serve paying patients as a way of building a sustainable fund for free outreach programs.

HATTORI is a highly skilled practitioner, currently regarded as one of Japan’s leading surgeons in vitrectomy and phaco surgery. Even if he is called “the man with the golden hands” because of his expertise as a surgeon, he insists that it is still the heart that matters most. Hattori is the epitome of a professional that has demonstrated the highest form of individual social responsibility.

In electing TADASHI HATTORI to receive the 2022 Ramon Magsaysay Award, the board of trustees recognizes his simple humanity and extraordinary generosity as a person and a professional; his skill and compassion in restoring the gift of sight to tens of thousands of people not his own; and the inspiration he has given, by his shining example, that one person can make a difference in helping kindness flourish in the world.

I stand here today, honoured and humbled to be conferred the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award, the greatest honour.

I am by no means an elite doctor. I kept failing entrance exams. It took me four years to be accepted at a medical school, and seven more years to graduate. But the reason why I did not give up is because of a promise I made to myself when I was seventeen years old. That was when I overheard the medical staff speaking disrespectfully to my father who was fighting his last fight against cancer. I said to myself then that I will become a doctor who can empathize with the feelings of patients. That conviction stayed has stayed with me since.

I parted with what comfortable life I had in Japan for a new challenge in Vietnam twenty years ago because of that same conviction. There was a shocking prevalence of cataract blindness in the country. What was more shocking was that patients typically would come to the hospital only when they are in a dire situation…when they have lost sight in both eyes.

I once met a six-year-old boy whose one eye was already light negative, the other with retinal detachment. He needed eye surgery urgently. But on the day of the surgery, he did not show up. He could not afford the surgery. How was this six-year-old going to live the rest of his life? Wasn’t there anything that I could have done? I have not been able to forgive myself since then for having let the boy go. That was when I decided that when patients cannot pay, I will simply tell them, “No worries, it will be alright. I will pay for you from my own pocket money, and so please have the surgery.”

Most of you may never have been conscious that you can see. Now, may I ask all of you here, to close both your eyes just for a moment? How would you feel if you have to live in that darkness for the rest of your life, and that you will have to depend on your family to assist you all your life? How would you feel, if you were that six-year-old boy?

Please open your eyes now.

It scares me too, to think of life without light. But that is precisely the situation millions of people still find themselves in today.

When a child cannot read or write, unable to go to school because of blindness, it means the child is deprived of the opportunity to explore the full potential of life that God has given. There are adults who cannot see, and live every day feeling helpless, useless and hopeless simply because they do not see the light ahead in life. If there is anything that I can do as an ophthalmologist, it is to bring light to such people, so that they will turn their despair to hope and live a better life that they deserve to live.

As I said, I am in no way an elite doctor. I am just filled with joy when patients smile when they see light again. I find happiness in working with the doctors that I trained, and in providing free treatments for people across the region in Asia.

My wish is to be where there is a need, where there are people who want to see light, because I know that regaining vision is not only about being able to see, but about discovering hope in life.

Let there be light. God bless you all.