- CHANG founded the magazine Sasangge, or World of Thought, that focused on providing creative and stimulating reading for students and their professors.

- Sasangge’s staff of professors, lawyers and writers, together with novelists and poets who have been introduced through the pages of the magazine have contributed significantly to the new Korean literacy movement that marks a national awakening after the 35-year Japanese occupation.

- In emphasizing in Korean life a concern for the individual and his nourishment of mind, Sasangge and its publisher have made a singular contribution, indicative of the potential in journalism and literature to become a power for the public good.

- The RMAF Board of Trustees recognizes him for his editorial integrity in publication of a nonpartisan forum to encourage dynamic participation by intellectuals in national reconstruction.

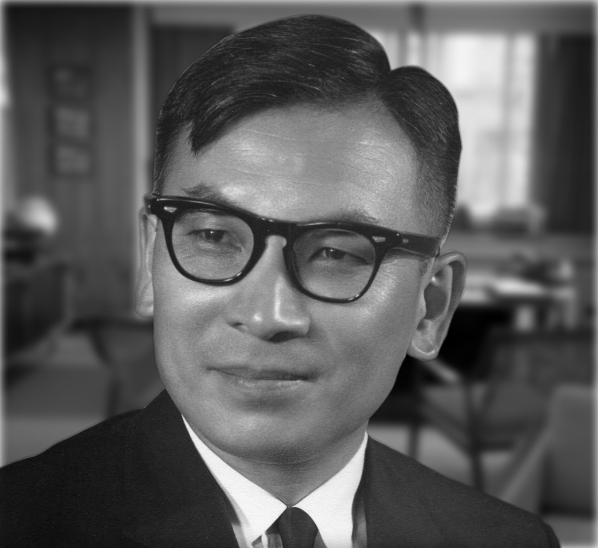

Amidst the cataclysmic events that have buffeted Korea during the past decade, CHANG CHUN-HA has devoted himself to enriching the “universe of discourse” that is fundamental to democratic progress. His vehicle has been Sasangge, or The World of Thought, a magazine born in the refugee-glutted seaport of Pusan in April 1953. Its purpose was not profit nor political power, but the enlightenment of the new generation of Koreans so that they might “discover the way” to building a freer society in harmony with their national traditions.

Sasangge has focused upon providing creative and stimulating reading for students and their professors; they held the promise of future leadership and afforded the opportunity for new competence in exploring national problems in the Korean language after 35 years of Japanese occupation and education.

A monthly publication of 400 or more pages, Sasangge is planned by an editorial board of 17 leading professors, lawyers and writers. The 21 staff members, most of whom are young Koreans educated after World War II, do extensive research in preparation of each issue. Novelists and poets who have been introduced through the pages of the magazine have contributed significantly to the new Korean literacy movement that marks a national awakening.

Although Sasangge is the product of effort by many talented Koreans, CHANG CHUN-HA’s role as publisher has been crucial. During times of political uncertainty and pressure for official conformity he has unobtrusively and steadfastly worked to insure for the magazine an independence of expression and tolerance of competing views. In the process the magazine has repeatedly sacrificed prosperity and easy popularity. While admitting that he is not always practical in a business sense, CHANG sets an example of simplicity in his personal life that is the price of an easy conscience in an unsettled time.

The advancement of a people is measured more in the ideas that move them than by their material accomplishments. In emphasizing in Korean life a concern for the individual and his nourishment of mind, Sasangge and its publisher have made a singular contribution, indicative of the potential in journalism and literature to become a power for the public good.

In electing CHANG CHUN-HA to receive the 1962 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Journalism and Literature, the Board of Trustees recognizes his editorial integrity in publication of a nonpartisan forum to encourage dynamic participation by intellectuals in national reconstruction.

A man of unbending will, a man of independence, a man whose life was dedicated to the spirit of liberty was the man Ramon Magsaysay. Not only was he a great leader but a great man whom Asia is proud to claim.

An award named after such a man, an award to honor and to perpetuate his greatness of spirit, integrity and dedication to liberty, the Ramon Magsaysay Award is most valued and prized not only by the people of Asia but by all people who love freedom.

Although I am the recipient of such an award, I am unable to look upon it simply as honoring me as an individual. The award, in fact, honors the Korean people.

I should like to take this occasion to make three important points.

First, I would rather not think of this 1962 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Journalism and Literature as granted only to me, alone. It is because of the existence of the magazine, Sasangge that I meet with this honor today. And Sasangge, in turn, has been able to continue and grow only through the wholehearted cooperation and devotion of the intellectuals of my country.

During the past 10 years since Sasangge started publication, Korea has seen several political upheavals, bringing instability and uncertainty to our economic and social life. Business, big and small, has seen many ups and downs. Publishing, in particular, has seen the greatest change as some 170 magazines have come and gone during the 10 years of Sasangge’s existence. Sasangge has been able to continue as if it were an exception — but only because of the unstinting support of Korea’s intellectuals.

In other words, Sasangge has been able to continue because Korean society felt a need for the magazine. Therefore, I am here merely as the representative of our contributors, the businessmen affiliated with us and the teachers, students, soldiers, public servants and many others who form our readership.

Such is the spirit in which I accept this award, and so express my sincere gratitude to the Magsaysay Foundation as a representative of Korea’s intellectuals.

Secondly, I look upon receiving this award here today as being charged, in fact, with the responsibility of propagating the spirit of Ramon Magsaysay among my countrymen. Moreover, as I am sure we all realize, the establishment of this award has created a medium through which the freedom-loving people of Asia have become more closely tied.

On the 20th of August, when it became known that I was to receive this award, the Korean press was unstinting in its report of the news. Our metropolitan and provincial newspapers, as one, were generous in their praise for the aspirations and spirit of Ramon Magsaysay.

Without doubt, this moment constitutes a new turning-point in the hearts of all Koreans who respond to the spiritual greatness of Ramon Magsaysay. The seed has been sown. And now it is abundantly clear that the heavy responsibility of fostering its growth and bringing it to fruition has fallen upon my two shoulders — no, upon the shoulders of every Korean intellectual. I realize the gravity of the trust and vow to do my best as long as I live to prevent discredit from befalling this award.

Thirdly, as a man responsible for maintaining the integrity and propagating the spirit of this award, I wish to make known the following decision through which I hope to magnify more fully its significance.

I shall devote all the money I am receiving to the establishment of an award for the advancement of Korean journalism. I have repeatedly announced this through our Korean newspapers and wish to make formal declaration of the fact here today. The details of this plan will be settled upon my return and after full consultation with my staff and others concerned. I believe this is the only way I can properly enhance the value of the Ramon Magsaysay Award which, as I have already mentioned, has been presented to the intellectuals of Korea.

Finally, as a representative of the Korean intellectual community, I would like to express our profound gratitude to the Philippine leaders who have been instrumental in the establishment of this award, to those organizations which have cooperated to make this award a symbol of the world’s free societies, to the trustees of this Foundation who have labored to select the awardees and to the bearers of a proud history, the people of the Philippines.