- He designed Khuda-ki-Basti, a housing project for the urban poor that imitated the way illegal squatters actually build their neighborhoods. Rejecting the stereotype of the poor as freeloaders and criminals, he saw the katchi abadis as centers of dynamism whose occupants were both industrious and resourceful.

- At SKAA, SIDDIQUI cut boldly through mounds of red tape to make it easier for katchi abadis to be regularized. He wrested control of the lease-assigning process from sluggish local councils and streamlined it, thereby giving slum residents swift security of tenure and making SKAA self-financing.

- He worked closely with the Orangi Pilot Project and NGOs to improve SKAA’s engagement with the communities and to enhance social services such as health care, family planning, credit, and education.

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes his demonstrating that a committed government agency working in partnership with NGOs and with the poor themselves can turn the tide against Pakistan’s crippling shelter crisis.

The slums of modern Karachi, known as katchi abadis, began as the shanty towns of Muslim Indian refugees to Pakistan at the time of Partition. They swelled in the 1950s as rural folk sought jobs in Karachi’s burgeoning industries and swelled again when civil war overtook East Pakistan in 1971.

These spontaneous settlements of the uprooted poor grew with such speed that they wholly outstripped the government’s attempts to control them, flooding the city center and forming hundreds of illegal “colonies†on its periphery. In them, the striving poor lived in squalor, without titles, without services, without sewers and drains and water mains. They still do, in more than five hundred katchi abadis. In them live 40 percent of Karachi’s population: four million people!

Addressing this reality in 1972, the government of Pakistan declared that katchi abadis should be legally acknowledged (or “regularizedâ€) and integrated into the city proper with infrastructure and services. But for many years thereafter little was accomplished. Urban councils failed at the task and so, too, did the Sindh Katchi Abadi Authority, or SKAA, which the government established in 1987 to address the squatter problem in Sindh Province. But when TASNEEM AHMED SIDDIQUI became director general of SKAA in 1991, things changed.

As a trainee at Pakistan’s prestigious Civil Service Academy, SIDDIQUI met Akhter Hameed Khan. The young SIDDIQUI imbibed the formidable Khan’s moral passion to alleviate poverty and also his community-building approach to doing so. Later, as director general of the Hyderabad Development Authority, SIDDIQUI designed Khuda-ki-Basti, a housing project for the urban poor that imitated the way illegal squatters actually build their neighborhoods. Rejecting the stereotype of the poor as freeloaders and criminals, he saw the katchi abadis as centers of dynamism whose occupants were both industrious and resourceful. Projects like Khuda-ki-Basti succeed, he says, because they tap the “poor’s huge potential for finding solutions to their own problems.â€

At SKAA, SIDDIQUI cut boldly through mounds of red tape to make it easier for katchi abadis to be regularized. He wrested control of the lease-assigning process from sluggish local councils and streamlined it, thereby giving slum residents swift security of tenure and making SKAA self-financing. He utilized practical low-cost technologies for SKAA infrastructure projects, weeding out corrupt contractors and reducing costs. He worked closely with the Orangi Pilot Project and NGOs to improve SKAA’s engagement with the communities and to enhance social services such as health care, family planning, credit, and education. Critically, SIDDIQUI and his staff established a working rapport with the katchi abadi dwellers themselves. They now install and pay for their own water and sewerage systems, maintain SKAA-built storm drains, coordinate the neighborhood leasing process, and collaborate with SKAA and NGOs to introduce the social services they most need. As active partners in upgrading their own neighborhoods, they are the key to the program’s sustainability.

Despite SIDDIQUI’s fast-track approach, the process is painstaking and slow. Many katchi abadis remain beyond the benevolent reach of SKAA’s small staff of 175. SIDDIQUI himself has been transferred in and out of the agency. Still, in hundreds of Karachi’s poorest neighborhoods, a quiet transformation has been set in motion.

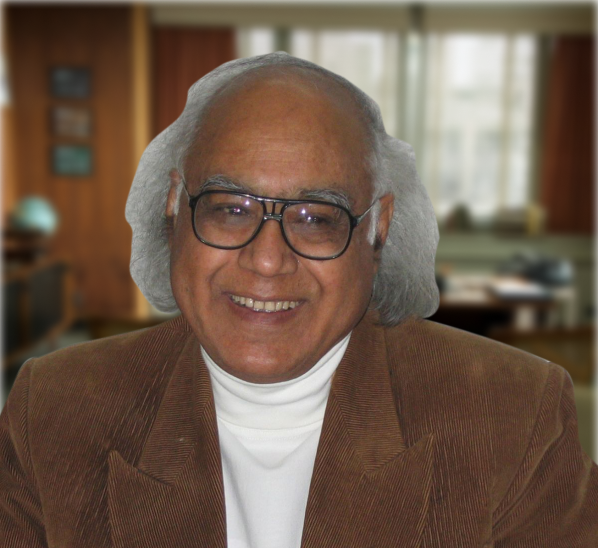

For someone who likes to shake up the system, fifty-nine-year-old SIDDIQUI is a man of mild manners and considerate ways. He is famously accessible. He returns phone calls. Yet, as a reformer, he has been stung by smear campaigns and bureaucratic reprisals. About this and about the magnitude of the task his agency faces daily, he says, “I am a realist.†And adds, “And an optimist.â€

In electing TASNEEM AHMED SIDDIQUI to receive the 1999 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Government Service, the board of trustees recognizes his demonstrating that a committed government agency working in partnership with NGOs and with the poor themselves can turn the tide against Pakistan’s crippling shelter crisis.

It is a great honour for me to accept this prestigious award. I feel particularly privileged because my election for this year’s Ramon Magsaysay Award, while recognizing that third world societies are in transition, supports the view that good government is possible if the method of governance were to be redefined and government decision-making made more participatory.

33 years ago when I joined the Civil Service of Pakistan, I was a young idealist. In my work I saw a great opportunity and potential to do good work for the country, particularly for the down-trodden and the under privileged.

Halfway through my career, the changing society in Pakistan changed more rapidly than the government could keep pace with. As a result, the writ of the government ran thin, and many of my colleagues fell victims to despair or opportunism. Apathy, indecisiveness and compromise became the hallmark of government service in Pakistan.

Against this discouraging background, I resolved to persist in my endeavor to understand the dynamics of change from the perspective of a civil servant. It was my observation that in spite of the government’s many weaknesses, there was sufficient space for organizing people and testing new concepts for achieving the prescribed objectives. What it needed was perseverance, a clear vision and commitment.

Once an outcast from the coveted Civil Service of Pakistan, my work gradually came to be recognized as a real option for reestablishing effective government. However, I must confess that I have not done anything great. I have only done what a good civil servant is expected to do.

Briefly, a few points need highlighting:

1. At a philosophical level, one can state the obvious: that it is better to light a candle than to curse the darkness. At a practical level, as government functionaries, rather than losing heart, it is our responsibility to search for options for maintaining social stability and economic development.

2. Rather than trying to replace government functions with non-government organizations, the government should use NGOs for research and demonstration so that its own functioning may be upgraded. It is the responsibility and mandate of the government to provide basic services to its people, especially the low-income communities.

3. The only way we can achieve effective government is by reforming it—not through slogan-mongering but through professional and persistent efforts on the part of the enlightened government functionaries, committed professionals and concerned citizens. Governments have also to discard conventional approaches and evolve pro-people processes of planning and implementation, based on structured partnerships with all relevant groups.

I hope the recognition of my work can help the cause of good governance in Pakistan. I also hope my younger colleagues in government will recognize the need for change, and find inspiration and direction in the work we have been doing in different facets of public life.

I thank you once again for the honor you have done me. I would also like to thank the many people who have and are continuing to work with me. I particularly wish to thank my wife and my children who have stood steadfast through difficult times, without whose encouragement and support I could not have pursued my professional compulsions so single-mindedly.