- Under his leadership, his theater group Ninasam’s repertoire grew to include Kannada-language renditions of Shakespeare, Moliere, and Brecht, as well as new plays by Kannada playwrights, plays for children, and modern adaptations of classics from the Indian canon.

- Ninasam’s success led SUBBANNA to form the Ninasam Theater Institute in 1980. In this “theater ashram,†fifteen students a year learn theater arts in a Gandhian atmosphere of simple living and hard work.

- Ninasam began introducing film classics to Karnataka audiences in the 1970s. Today, participants in its annual film-appreciation course view works of leading filmmakers like Satyajit Ray and Akira Kurosawa, both former Magsaysay awardees, and Ingmar Bergman.

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes his enriching rural Karnataka with the world’s best films and the delight and wonder of the living stage.

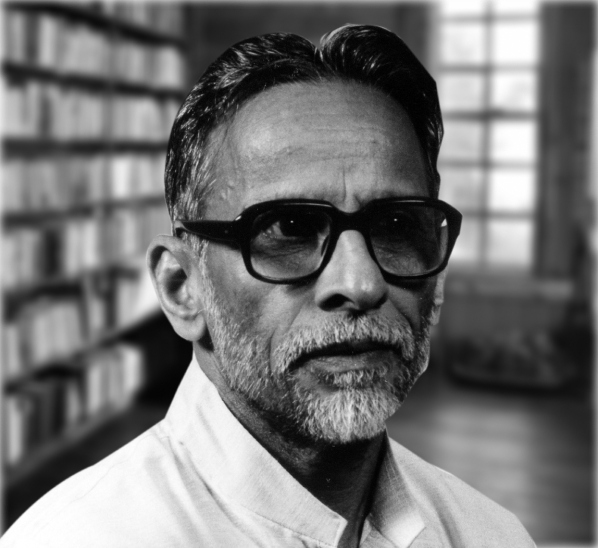

In recent years Asia’s prosperous urbanites have discovered the rural arts. Handicrafts from villages now adorn their city homes. Meanwhile, polished versions of country dances and plays appear on television and grace official extravaganzas. Yet the finer elements of urban culture are rarely introduced to the village world; its inhabitants are thought too unsophisticated to appreciate them. By introducing modern plays and films to rural folk in southern India, K. V. SUBBANNA is making a powerful case for the universality of art.

The rural town of Heggodu is home to some five hundred people in the Kannada-speaking state of Karnataka. There, areca palms and betel-pepper vines provide members of the SUBBANNA family with a comfortable living. But theater is their passion. In 1949 SUBBANNA formed the theater group, Ninasam, to stage local favorites based on the Indian epics Ramayana and Mahabharata; his father became the group’s first president.

After finishing a literary degree at Mysore University, SUBBANNA returned home with fresh ideas for Ninasam. Under his leadership, its repertoire grew to include Kannada-language renditions of Shakespeare, Moliere, and Brecht, as well as new plays by Kannada playwrights, plays for children, and modern adaptations of classics from the Indian canon. With help from the state government, he built a large local theater, a rarity in rural India, and introduced modern staging and lighting. Heggodu’s citizens liked what they saw—and came back for more.

Ninasam’s success led SUBBANNA to form the Ninasam Theater Institute in 1980. In this “theater ashram,†fifteen students a year learn theater arts in a Gandhian atmosphere of simple living and hard work. An itinerant troupe formed from the institute’s graduates perform Ninasam’s plays the length and breadth of Karnataka—often in open-air theaters before crowds of seven hundred or more. Following Ninasam’s example, and with its practical assistance, local theater companies are now being formed in other rural districts.

Film followed theater. Ninasam began introducing film classics to Karnataka audiences in the 1970s. Today, participants in its annual film-appreciation course view works of leading filmmakers like Satyajit Ray and Akira Kurosawa, both former Magsaysay awardees, and Ingmar Bergman. By showing such films, Ninasam is bridging the gulf between rural and urban cultures. India’s democracy, SUBBANNA believes, demands cultural diffusion of this kind.

Playing many parts in his time, SUBBANNA also crafts traditional Indian myths and tales into plays that probe modern issues. As a publisher, he brings out new works by regional writers as well as his own poems and translations of foreign movie scripts and books.

With financial prudence and a gift for bringing others into leadership, SUBBANNA has built Ninasam to last. Its headquarters in Heggodu boasts a library, rehearsal hall, guesthouse, and office, in addition to its famous theater. At fifty-nine, SUBBANNA says, he now leaves most of the real work to junior colleagues who include his son, Ashkara. But as one admirer has pointed out, self-effacing SUBBANNA still carries on multiple projects, “seemingly oblivious to the scale of his activities.â€

In electing K. V. SUBBANNA to receive the 1991 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Journalism, Literature, and Creative Communication Arts, the Board of Trustees recognizes his enriching rural Karnataka with the world’s best films and the delight and wonder of the living stage.

Ours is a land of rivers, and yours, of seas. From the people of my land of rivers, I bring love and greetings to you, people of land and seas. Kindly accept them.

Yours is a land of nobility and generosity. You have instituted this award to weave the Asian peoples together in friendship and to recognize and foster the new-sprung sprouts of the vitality of our continent in far-flung corners of our various nations. And by instituting it in the name of Ramon Magsaysay, one of your national leaders as well as a great Asian personality, you have made this award still more valuable. Many of my distinguished fellow countrymen have already been given this honor. Now, when you bestow the same honor on me, I accept it with deep happiness, acknowledging the love and nobleness of your people and remembering my predecessors who have received it. I accept it humbly and gratefully.

I have my reservations about the practice of giving or receiving awards in a democratic system. Yet, this award has brought me immense happiness. Although the award has been conferred on me, it is very clear that it has not come to me alone or to me in my personal capacity. If it were a smaller award than this, it might have given rise to such an illusion. But this is a very big award, so big that I cannot entertain any such illusions. The award has, in fact, been conferred upon the institution of which I am just a representative figure—the Ninasam Institutions; the Akshara Publications; my village, Heggodu; and my state, Karnataka. Thus this is an award that, far from bloating my ego, rather fills my heart with a genuine joy.

India is a vast country, composed of a number of large and small states. My state, Karnataka, neither too big nor too small, has an area and a population about three-quarters that of your country. We have in India about twenty different regional languages, with their own distinct histories going back about one or two thousand years, and all very rich in literature. My own language, Kannada, is about two thousand years old and has a great literary tradition. And our modern literature has such vitality and variety that it can easily occupy a unique place in world literature.

In Karnataka there are the Western Hills, where it rains plentifully, and the hills are covered in lush evergreen forests. Amidst these hills, far away from city centers and nestling among the forests, is my little hamlet, Heggodu. Its population is a bare five hundred. This hamlet, and another ten or twelve still smaller hamlets around it, make up what can be called a rural commune. And the Ninasam Institutions are a symbol of this commune’s tireless endeavors to realize its dreams of a new India.

England physically occupied our country for scores of years. All through this period, the “scientific civilization†of the Northern Hemisphere carried out a relentless attack upon us, an attack continuing even in the present time. But terming it an attack, in the same sense as a physical attack, is not so simple, as it raises many complex and important questions.

In his film Rashomon, the great Japanese director Akira Kurosawa tells the story of a bandit and a samurai and his wife. But the film is ambiguous. Did the bandit rape the samurai’s wife, or did she, in fact, feel attracted and offer herself to him? Did the bandit murder the samurai, or did the samurai commit suicide? The relationship and the interaction between us and Western scientific civilization is, likewise, very complex in nature. It is, at the same time, an aggression as well as a self-offering, a conflict and a communion, a confrontation and a coition.

This process of conflict and confluence is not limited to India. It is, in fact, a worldwide phenomenon. The various underdeveloped and developing countries of that large part of the globe we call the Third World have all been participants in this great churning. They have all, in their own manner and corresponding to their respective traditions and histories, generated specific responses to this challenge.

Although the Third World countries have put up a strong resistance to this scientific civilization, it cannot be denied that ultimately this same scientific civilization has been the propelling power of human history for several centuries. Besides its advancements in science and technology, it has propagated new ideas and values, such as liberty, equality, and democracy. These same values were accorded high importance in ancient times, but the credit for making them the vital center of human life and realizing them in concrete terms goes entirely to the modern scientific civilization.

Take the example of our own country. Through a long cultural history, we had built up a rich and complex tradition. Yet the same tradition had made our culture totally inhuman in many respects by generating and legitimizing caste division and discrimination, a cruel degradation and evil dogmatism, and a senseless, soulless barbarism. It was the scientific civilization that fully opened our eyes to these depravities.

But this scientific civilization now seems irrevocably set on a tragic course. This is probably due to the perversions that it engendered within itself. The people who shaped this civilization suffered under an illusion that they alone constituted the world and that all other people and parts of the earth were mere raw materials and tools for their own progress.

Freedom and equality are values that constitute a dialectical whole. We need to comprehend their dialectical aspects simultaneously if we aspire to achieve an essential balance, or samatva, as we call it in our language. The slightest tilt of this balance could result in the destruction of both values.

One-half of modern civilization, the capital-centered, freedom-oriented bloc, has stressed freedom, while the other half, the proletarian-centered, equality-oriented bloc, emphasized equality. Nevertheless, do we not today find that both these camps have destroyed both values?

One of our greatest political thinkers and activists, Ram Manohar Lohia, used to say that for our Third World, the modes of the scientific civilization were irrelevant and meaningless. Despite their extreme differences in external terms, the ultimate objective of both is the same: development. For them, development only means multiplying the means of material comforts and pleasures, moving forward in a linear pattern. Where can this kind of multiplicatory materialism finally lead mankind? What salvation can we hope for from this soul-denying, self-fueling, and self-consuming system? Is this kind of materialism to be the most desirable and the ultimate objective of mankind?

This fragmented concept of development has serious flaws and harms because, while human desires seem to be insatiable, nature is not inexhaustible. It cannot and will not yield to us forever, as we have been learning. Moreover, the driving force behind this kind of development, and its yardstick, is competition, which in its turn only generates aggression, envy, enmity, and violence.

At this stage in our world’s history, the thinking and the experiments carried out in the Third World over the ages could well prove to be vitally important. We in India, for instance, have not lost our memories of the Buddha, who as long as two thousand years ago said that desire was the root cause of evil; nor of our culture, which holds simplicity and restraint as two of the primary virtues. In our own time, Mahatma Gandhi was a living expression of such beliefs.

Gandhi wanted decentralization and moral restraint to be our ultimate goals. In place of mutual competition, he advocated mutual love and cooperation. For him, progress or development was not an exclusive, linear movement, but rather an all-inclusive holistic process. Here every human being would be able, within his own limitations and within the framework of his own space, time, and society, and in consonance with his fellowmen, gradually to achieve self-fulfilling self-expression. He termed this process sarvodaya—the ennoblement of all, together, at the same time.

Vinoba Bhave, a disciple of Gandhi and himself a recipient of the Magsaysay Award, tried all through his life to make sarvodaya a central principle of our national life. His ideas, though never fully implemented, yet have had a fundamental influence on our social consciousness.

Along with Gandhi and Bhave, we also have Dr. Ambedkar, a truly extraordinary figure. Born into the lowest strata of our social hierarchy, an untouchable, he broke down the most rigid and cruel walls that our ossified society had built and attained a peak of excellence with our people conferring on him leadership of the group that framed our modern constitution. A similar personality was Gopala Gowda, who arose from very humble circumstances, yet he organized the tenant farmers of our region and began a people’s movement that achieved national significance.

Our modern history has thus been a constant exploration for a balance, a proper balance in terms of political and philosophical pursuits, social relations, and economic equations. While persons like Gandhi and Bhave, coming from privileged classes of our society, taught us spiritual strength, those like Ambedkar and Gowda, coming from the deprived classes, trained us in political and people power.

The whole process of Third World countries searching for a meaningful new balance can also be viewed from another perspective. It is a process where the “thesis†of our several cultures confronts the “antithesis†of the modern scientific civilization, thereby creating an integrative, new “synthesis.â€

The honor that you have conferred on me—recognizing me as a representative link in an endeavor being carried out in a rural corner of my country—is really an honor given to all of us of the Third World engaged in forging a new synthesis, a new integrative way of life. I can never forget that I am but a little link in this movement, even in my own land. The work of my institution is only a continuance of our tradition.

For example, Shivarama Karanth, one of our most original intellectuals—a polyglot Leonardo da Vinci-like figure who can easily be counted among the world’s greatest writers—carried out similar activities forty years ago in a remote corner of our state. Now stepping lightly into his nineties, he continues to be a living inspiration to us all; when we built an auditorium for our Ninasam Institute, we could think of no more worthy person to name it after.

The Magsaysay Award has often been compared with the Nobel Prize, an honor usually bestowed for individual excellence and personal achievement. The Magsaysay Award, I feel, is given more in consideration of the attitude, the mode, and the social aspect of an achievement rather than of the achievement itself. A case in point is the late Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay of our country who is one of those honored by you. She had no extraordinary excellence in any of the activities she pursued. There were a number of others who were better political workers, social reformers, organizers, and artists than she. But there was no one else who combined all these talents so well in a single personality and made them all so significantly relevant to her society.

The choices for this award have thus really brought into focus a new holistic, all-inclusive, and integrative worldview that is essentially an alternative to the Western view.

I express once more my love and gratitude to your courageous people, the first in Asia to cast off the colonial shackles, and to your land and waters, the first in Asia to be graced each day by the sun’s hope-giving, healing rays.

I accept your honor with deep humility and happiness.