- In Lahore, he found his vocation in journalism, rising from post to post at leading Pakistani publications to become chief editor of the Pakistan Times in 1989. By 1993, REHMAN had left The Times, under pressure for criticizing the government.

- In September 1994, REHMAN joined twenty-four like-minded Indians and Pakistanis in Lahore to open a public dialogue for reconciliation and peace which led to the formation of the Pakistan-India Peoples’ Forum for Peace and Democracy.

- The Forum’s chief weapon was dialogue to promote demilitarization, denuclearization, and peace and to publish resolutions insisting upon mutual arms reductions and troop pullbacks; an end to cross-border provocations; and a “peaceful, democratic solution” in Kashmir.

- For REHMAN, the Forum’s peace initiative grew naturally from his work as one of Pakistan’s leading human rights advocates and as long time director of the internationally esteemed Pakistan Human Rights Commission.

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes them for reaching across a hostile border to nurture a citizen-based consensus for peace between Pakistan and India.

The armed standoff between India and Pakistan has endured for more than fifty years, bringing with it four outright wars and continuing upheaval. Its flashpoint is Kashmir, claimed by both sides, but its roots lie in the shocking communal violence of Partition in 1947. In the years since then, memories of this disturbing event have fueled religion-infused nationalism and militarism in both countries and kept millions of fearful people poised for war. Today, both sides boast nuclear weapons and the stakes are global. The problem seems intractable. But IBN ABDUR REHMAN of Pakistan and LAXMINARAYAN RAMDAS of India believe there is hope. As leaders of the Pakistan-India Peoples’ Forum for Peace and Democracy, they are building popular support for peace on both sides of the border.

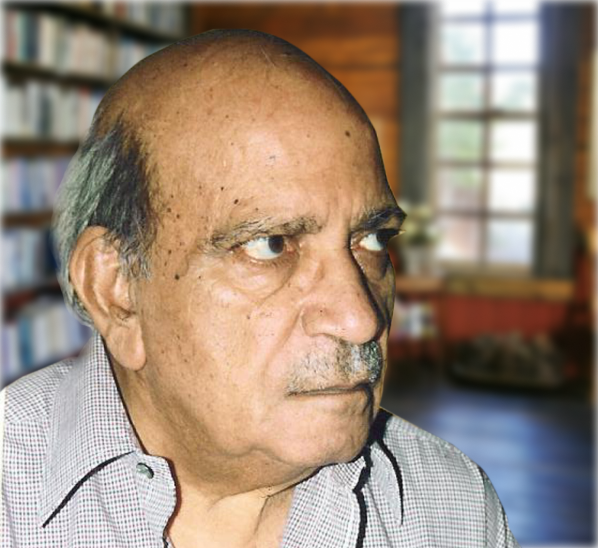

ABDUR REHMAN, a Punjabi Muslim born in 1930, was away at Aligarh University in 1947 when Partition violence erupted in his hometown and several members of his family were killed by rampaging communalists. LAXMINARAYAN RAMDAS, a Hindu from Mumbai, was fourteen at the time and living in Delhi. He remembers angry mobs threatening his parents for protecting a Muslim family. REHMAN was obliged to migrate to Pakistan with his father. In Lahore, he found his vocation in journalism, rising from post to post at leading Pakistani publications to become chief editor of the Pakistan Times in 1989. RAMDAS became a cadet at India’s Armed Forces Academy in Dehradun and, later, the Royal Naval College in Dartmouth, England. He rose from command to command until, in 1990, he was named chief of India’s navy.

By 1993, REHMAN had left The Times, under pressure for criticizing the government, and Ramdas had retired and acquired a Pakistani son-in-law. As tensions again rose between India and Pakistan, both men sought to influence their countries to change course. In September 1994, REHMAN joined twenty-four like-minded Indians and Pakistanis in Lahore to open a public dialogue for reconciliation and peace. This led to the formation of the Pakistan-India Peoples’ Forum for Peace and Democracy. REHMAN became founding chair of the Pakistan branch; RAMDAS was named vice-chair of the India branch and became chair in 1996. Both men guided the organization until 2003.

The Forum’s chief weapon was dialogue. In a series of conventions beginning in 1995, it drew hundreds of Indians and Pakistanis together to promote demilitarization, denuclearization, and peace and to publish resolutions insisting upon mutual arms reductions and troop pullbacks; an end to cross-border provocations; and a “peaceful, democratic solution” in Kashmir. Meeting alternately in Pakistan and India, the conventions sustained this dialogue for ten years and more as the Forum’s base grew to embrace a web of environmental, human rights, trade union, and women’s rights activists as well as concerned citizens from the academe, industry, and the professions.

During the same years, the Forum organized people-to-people delegations of lawmakers, diplomats, soldiers, artists, and students to open friendly talk channels between Indians and Pakistanis and to counteract propaganda in each country stigmatizing the other. And it campaigned for the liberalization of travel between the two countries and for the revision of hate-filled school textbooks. At another level, Forum leaders such as REHMAN and Ramdas worked behind the scenes with national leaders and opinion makers to promote the peace agenda. The Forum’s mission is not grandiose. “It is enough,” REHMAN says, “to contribute in easing the tension between the two countries by providing opportunities for people to meet.”

For REHMAN, the Forum’s peace initiative grew naturally from his work as one of Pakistan’s leading human rights advocates and as longtime director of the internationally esteemed Pakistan Human Rights Commission. In this role and also as a journalist, REHMAN has devoted decades to exposing systemic violations of the rights of women, children, workers, and minorities in Pakistan and to fighting corruption and the abuse of power. He has been a champion of democracy as a secular ideal in a country where, he says, “authoritarianism has been the rule and short-lived democratic facades an exception.” All this at considerable personal risk and sacrifice. As for India and Pakistan, he calls upon both countries to reject their “pathological obsession with the politics of hostility.”

RAMDAS says, “I entered the armed services as a hawk and exited as a dove.” His military career made him intimately familiar with the limitations of military solutions to political problems. This led to his role in the Forum. Still, India’s explosion of a test atomic bomb in May 1998, RAMDAS says, “was one of the greatest turning points in my life.” In July, he signed a public declaration by retired military men declaring that “nuclear weapons should be banished from the South Asian region, and indeed from the entire globe.” With his wife, Lalita, he threw himself into the antinuclear cause, warning Indians and Pakistanis alike about their country’s unreliable “control and command systems” and about the naivete of nuclear deterrence.” Touring and speaking extensively, he exhorted everyone to guard against the seductiveness of solutions “through super-violence.”

RAMDAS and REHMAN both connect the problem of peace in the subcontinent to dangerous ideologies that associate religion with nationalism and patriotism, and to militarism and other antidemocratic forces. REHMAN rues his own country’s “absence of genuinely democratic institutions.” And RAMDAS has linked recent political trends in India to “the path to fascism.” Both have been smeared as traitors, but they are not moved. It is time to stop the belligerent shouting and listen to other voices, they say. When it comes to war and peace, REHMAN likes to say, “I believe the people are a little ahead of the governments.”

In electing IBN ABDUR REHMAN and LAXMINARAYAN RAMDAS to receive the 2004 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Peace and International Understanding, the board of trustees recognizes their reaching across a hostile border to nurture a citizen-based consensus for peace between Pakistan and India.

Chairman and Trustees of the Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation Distinguished Guests, Fellow Awardees and Dear Friends.

I am extremely grateful to the trustees of Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation for selecting me as one of the two winners of the 2004 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Peace and International Understanding. While I am overwhelmed by the honour done to me, I accept this award on behalf of thousands of supporters of the Pakistan-India Peoples’ Forum for Peace and Democracy, who have struggled for a whole decade to find democratic and peaceful solutions for the problems that have bedeviled the people of not only India and Pakistan but the whole of the South Asian region.

You are all familiar with the history of conflict and confrontation between two of South Asia’s largest states, the wars they have fought and the large scale diversion of their resources as preparation for bigger conflicts. The struggle for peace between these two neighbours has acquired much greater urgency since both of them acquired nuclear weapons and started a prohibitively expensive missile race.

It has been our experience in South Asia that absence of armed conflict does not amount to peace. For five decades the governments of Pakistan and India have been frittering away their resources on preparations for war and the people have been paying a heavy price in the name of defence even during periods when there is no fighting along the borders. It has also been our experience that peace is not an ideal that can be pursued in isolation from other concerns of the people. That is why the Pakistan-India Peoples’ Forum for Peace and Democracy has from the outset viewed peace as part of a comprehensive package that includes disarmament and denuclearization, democratic governance, promotion of a culture of tolerance and resistance to extremism in the name of belief and ideology, and democratic resolution of matters such as Kashmir. During the last couple of years forces of peace and justice across the globe have come under strain as a result of substitution of the ideal of peace with the gospel of security. South Asia too has faced attempts to devalue peace.

While facing these challenges we are sustained by the support of a very large number of ordinary women and men in both countries who do not correspond to the images of Indian and Pakistani people the world media carries everyday. These people who constitute a majority in South Asia are neither blood-thirsty fundamentalists nor intolerant zealots out to convert the world. They live by their labour and are striving to realize their dreams of a better life for their children. I am happy that the honour done to my dear friend Admiral Ramdas in India and myself will enable the world to recognize these peaceful millions and also encourage them to pursue the goal of peace and their fulfillment.

I thank you again for the honour.