- He was the interim prime minister of a successful coup in 1991, chosen as the acceptable leader until elections could be held. ANAND who was a widely respected business leader, disapproved of military coups and accepted the premiership only from a sense of duty.

- He launched a period of reform which included expanding press freedom, combating the spread of AIDS, enacting Thailand’s first comprehensive environmental law, promoting support for education, insisting upon transparency in the state’s joint ventures with private companies, and generating millions of extra public revenue by renegotiating questionable deals between the previous government and its favored companies.

- Elections in 1992 brought to power the chief architect of the 1991 coup, to the outrage of citizens. Pro-democracy demonstrators in Bangkok were killed by the military; nearly a hundred died. Thailand’s king intervened to pave the way for a democratic restoration. ANAND was called, once again, to assume the interim premiership and organize credible elections. Three months later, he passed the reins of leadership to a freely elected government.

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes his sustaining the momentum for reform and democracy in Thailand in a time of crisis and military rule.

The bloodless revolution that ended Thailand’s absolute kingship in 1932 also heralded democracy. But in the years thereafter, military coups d’etat, not elections, became the common landmarks of political change in Thailand. Generals dominated government, rarely elected civilians. By 1990, however, after a decade of hopeful change, many Thais believed that democracy was at last taking root in their country. But the army struck again in February 1991. Promising new elections in due course, the successful coup plotters chose an esteemed civilian to serve as interim prime minister: ANAND PANYARACHUN.

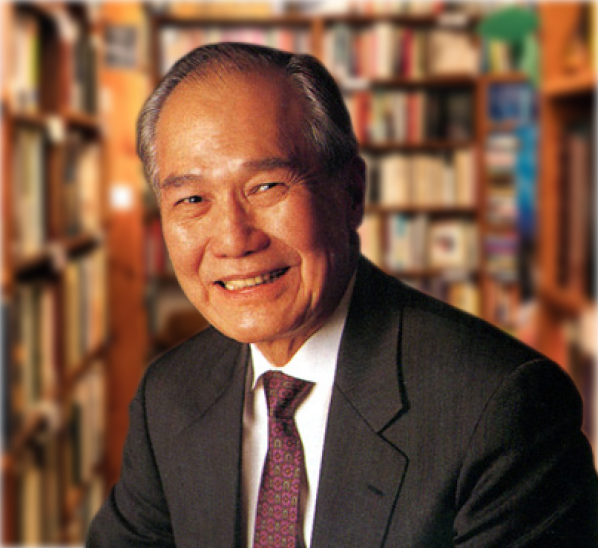

Born in 1932, ANAND ascended through schools in Bangkok and London and earned his B.A. (Honours) at Trinity College, Cambridge. He joined Thailand’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and subsequently served as its Permanent Representative to the United Nations and as ambassador to Canada and the United States. As Permanent Secretary for Foreign Affairs under a civilian government, he paved the way for reconciliation with China and Vietnam and opposed the continued presence of American military bases in Thailand. As a result, when yet another coup returned the army to power in October 1976, he was branded a communist-sympathizer. Exonerated by an investigation panel, he was assigned to a post abroad. In 1979, he resigned and entered business. By 1990, ANAND was Executive Chairman of the Saha-Union conglomerate and a widely respected business leader.

ANAND disapproved of military coups and accepted the premiership only from a sense of duty. Acting with surprising independence and broad public acclaim, he launched a volley of reforms. He expanded press freedom, committed the government to combat the spread of AIDS, enacted Thailand’s first comprehensive environmental law, promoted philanthropy and private support for education, insisted upon transparency in the state’s joint ventures with private companies, and generated millions of extra public revenue by renegotiating questionable deals between the previous government and its favored companies. Hundreds of vexing regulations were updated or eliminated. ANAND’s aggressive pursuit of privatization, tax reform, and trade liberalization stoked the country’s economy and helped win the confidence of investors at home and abroad. All this in one year’s time!

Elections in March 1992 brought a new crisis. When victorious military-linked political parties named the chief architect of the 1991 coup as prime minister, outraged citizens protested. In May, government soldiers fired upon pro-democracy demonstrators in Bangkok; nearly a hundred died. Thailand’s king now intervened to pave the way for a democratic restoration. ANAND was called, once again, to assume the interim premiership and organize credible elections. Three months later, he passed the reins of leadership to a freely elected government.

ANAND then returned to Saha-Union. In the years since, he has remained an influential public figure, investing his energy and prestige to harness the resources and goodwill of business on behalf of the environment and to advance other social and political reforms.

Thailand’s democracy is still fragile and flawed by corruption. Yet ANAND remains a believer. “It is no longer in question whether we should opt for economic development or democracy,†he asserts. “The two must proceed together.†As a leading member of the assembly drafting his country’s new constitution, he has labored to strengthen democracy in Thailand by securing civil liberties, making government more accountable to citizens, and eliminating vote buying and other scourges of money politics.

A straight-speaking and patient man, sixty-five-year-old ANAND knows that not all of Thailand’s problems will be solved in his lifetime. “Diplomats and businessmen are taught to be realists,†he says. “As an ex-diplomat working in the business community, I am very much a realist. â€

In electing ANAND PANYARACHUN to receive the 1997 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Government Service, the board of trustees recognizes his sustaining the momentum for reform and democracy in Thailand in a time of crisis and military rule.

I am honored to have been conferred the 1997 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Government Service.

This Award carries the name and spirit of a great Asian leader, one known for his unstinting efforts to pursue reform in every segment of Philippine life. President Magsaysay’s commitment to reform for the benefit of Philippine society and his well-deserved reputation for incorruptibility provide us with a shining example of Asian values.

Throughout my own life and career, I have tried to pursue the same goals. It has been my view, tested in the crucible of my public and private careers, that the advancement of Asian societies can be achieved only in the presence of good governance, including:

First, an honest government, one that serves the interests of the people; Second, an efficient government, one that provides good value for money; Third, a just government, one that endeavors with sincerity and vigor to minimize economic and social inequalities.

Above all, good governance requires compliance with the precepts of democratic rule.

The lessons of the twentieth century are clear. First, no nation can any longer afford to base its prosperity, its security, and its future on military might. Second, no nation can any longer feel secure if its citizens are deprived of the opportunities for meaningful participation in political, economic, and social life. Third and most important, real security can only derive from a nation’s inner strength, the well-being of the people.

In accepting this Award, I do so on behalf of the many Thais who have pursued the same goals that I have striven for, namely, the building of a democratic society, emphasizing people’s participation, economic prosperity, and social justice.