- Jose pursued his career in journalism as managing editor of the Manila Times Sunday Magazine, editor of Progress and later Comment, and in Hong Kong as managing editor of Asia Magazine.

- In 1965, he opened the Solidaridad Book Shop and Publishing House, and the following year launched Solidarity, a monthly magazine of comment on current affairs, ideas and the arts. A year later he opened the Solidaridad Galleries to allow little known artists an outlet for their work.

- In his writings he has expressed that dimension of caring about human beings that separates trivia from writing of worth.

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes his intellectual courage and his concern for and encouragement of Asian and other writers and artists, for many of whom his Solidaridad Book Shop is a cultural mecca.

The life confronting writers and artists who will not compromise their self-expression is at best uncertain. Poets and painters who in times past have been appreciated and honored by courts and a scholar gentry, in the developing world today may receive only passing notice amidst the scramble for wealth, privilege and power. Mass communications catering to the lowest common denominator of taste occupy the public attention. Values most needed are frequently lost from sight.

It is the hard task of serious writers and artists in this setting to survive and be effective; the quality of their creativity alone is no guarantee. Only by joining in common cause with like-minded men and women can they become significant. This, in turn, requires self-effacing leadership, a stimulating, congenial gathering place and forums for publication or exhibition.

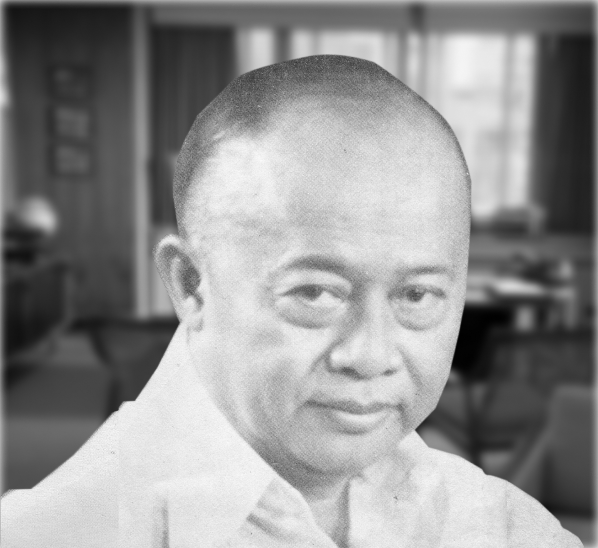

FRANCISCO SIONIL JOSE’s role in this many-faceted arena is a product of his wit and formative experience. Born into a poor family in the Philippine province of Pangasinan in 1924, he learned as a boy the hard life of a farmer, following a water buffalo to plow the rice field. After high school he worked with the U.S. Army Medical Corps during the 1945 battles for northern Luzon. Lacking funds for a medical education, he worked his way through school as a liberal arts student at the University of Santo Tomas. There he had his first experience in journalism, working on the collegiate Varsitarian and later on Commonwealth, the national Catholic weekly.

JOSE pursued his career in journalism as managing editor of the Manila Times Sunday Magazine, editor of Progress and later Comment, and in Hong Kong as managing editor of Asia Magazine. After two years as Information Officer for the Colombo Plan in Sri Lanka, he returned to Manila in 1965 to open the Solidaridad Book Shop and Publishing House, and the following year launched Solidarity, a monthly magazine of comment on current affairs, ideas and the arts. A year later he opened the Solidaridad Galleries to allow little known artists an outlet for their work.

Possessed of prodigious energy and curiosity, JOSE made himself an authority on land tenure and in 1968 became a consultant to the Department of Agrarian Reform. He had earlier been a founder and national secretary of the Philippine PEN and a moving spirit in the International Association for Cultural Freedom. He continued as a prolific writer of essays, short stories and novels, some of which have been translated into half a dozen languages, all the while lecturing at universities in the Philippines and abroad.

Although it is difficult to quantify, JOSE has probably made his greatest contribution through the guidance and assistance he has offered numerous Filipino and foreign writers, artists and scholars. From Europe, Asia, Australia and the Americas they have come to browse among the carefully selected titles in his bookstore and glean ideas.

JOSE has earned only a modest living through his many activities. He has won instead, for the Philippines, himself, his wife Teresita and their seven children, who all help manage his enterprises, a roster of extraordinary international friends. He has fostered a cultural and intellectual exchange which is enriched by his abiding solicitude for the welfare of ordinary people and enlivened by his vigorous sense of humor. In his writings he has expressed that dimension of caring about human beings that separates trivia from writing of worth.

In electing FRANCISCO SIONIL JOSE to receive the 1980 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Journalism, Literature and Creative Communication Arts, the Board of Trustees recognizes his intellectual courage and his concern for and encouragement of Asian and other writers and artists, for many of whom his Solidaridad Book Shop is a cultural mecca.

In times like these when a writer can best express himself, perhaps, in allegory, let me tell you a very short story.

A long time ago there lived in the Central Plain of Luzon a boy who liked to read. His forefathers had come down from the north and had cleared the virgin land only to be dispossessed by influential men afterwards. The little boy’s mother was God-fearing and hardworking and she taught her children those solid Ilocano virtues of patience and industry, without which they would not be able to endure the drudgery of the village.

That boy was free; he raced the wind and breathed God’s sweet air. He learned how to read and a new world opened up for him. His teacher lent him the novels of Rizal and he wept over the fate of that hapless, demented woman, Sisa, and her two sons. He wandered with the settlers in the prairies of Nebraska in Willa Cather’s My Antonia. And at night, when there was no kerosene for their lamp, he would walk to the far corner where, under the streetlight, he joined that knight errant, Don Quixote, in his misadventures.

Then the boy left home; kindly relatives took him to the city to study. He worked his way through college, writing short stories for a living since that was the only thing he knew. He fell in love, got married and raised a family. In time, he traveled far and, on occasion, he even dined with the mighty. He lost a bit of his naivete and his good humor but, always, he treasured memories of the village where he was born.

After many years he returned to it, and to his profound dismay he saw that the village had hardly changed, that his relatives and his old friends had not read what he had written. And seeing them, he asked himself why they were still poor and why he was comfortable.

His city friends asked why his novels were sad. They were sad because memory had chained him to a past afflicted with injustices and, as he looked around him, the same injustices still prevailed. His stories were melancholy because he realized the inadequacy of his response—the futility of words.

In writing it was not his intention to present a bleak human landscape. He had sought communion with any man in any village, hoping that he would be able to express the aspirations of those he had left behind. It was their agony, instead, about which he wrote. The boy who had raced the wind was now shackled. He had become a man and deep in his heart he knew he had left his village forever.

Please bear with me and the memory with which I am burdened. This Award makes it lighter. I accept it gratefully, remembering the many individuals with whom I have worked who believe in the dignity, not only of writers, but of all men, particularly those who have less in life and therefore less in law—whereas they should have more.

I accept this Award humbly, remembering those I have left behind who have suffered for truth and justice with a courage and fortitude that will never be mine.