- He published his first stories and poems in 1953, the year before he graduated from the University of Santo Tomas.

- A Fulbright Fellowship took him to the University of Indiana where he earned a PhD in Comparative Literature and wrote a now-classic study of Tagalog poetry.

- Stirred by the wave of passionate nationalism sweeping Philippine campuses in the late 1960s, LUMBERA included more vernacular readings in his literature and drama courses.

- LUMBERA wrote and lectured prolifically on literature, language, drama, and film. He composed librettos for new musical dramas such as Rama Hari and Bayani.

- The RMAF Board of Trustees recognizes his asserting the central place of the vernacular tradition in framing a national identity for modern Filipinos.

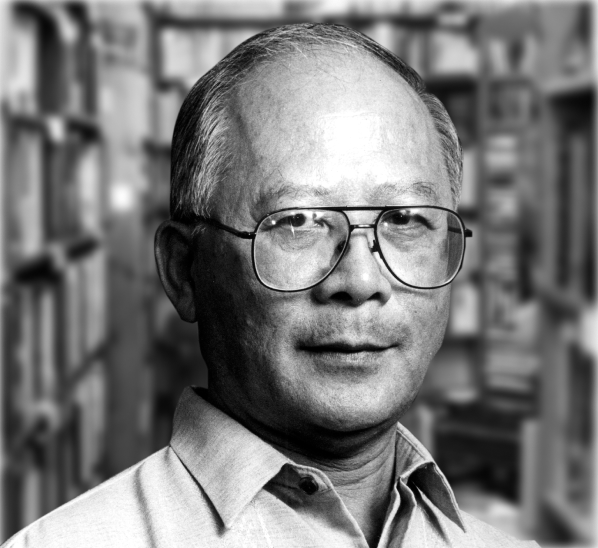

Few cultures in Asia have been so profoundly affected by contact with the West as that of Filipinos. Spaniards and Americans brought to the islands, among other things, their own languages and literary forms. While Filipinos rejected some foreign elements, they adopted others and formed a unique Asian culture of their own. Inevitably, perhaps, the higher arts came to be dominated by Western models. Literature was written in Spanish, or English; everything else was mere Filipiniana. This was the view, at least, of the academic establishment and most members of the Spanish and English-speaking classes. BIENVENIDO LUMBERA has challenged this point of view and restored the poems and stories of vernacular writers to an esteemed place in the Philippine literary canon.

Born in 1932 in Lipa City, Batangas, LUMBERA attended local schools where his teachers remarked on his unusual facility with language. Encouraged, he became an avid reader and entered the University of Santo Tomas with the hope of becoming a creative writer. He published his first stories and poems in 1953, the year before he graduated. A Fulbright Fellowship took him to the University of Indiana where he earned a PhD in Comparative Literature and wrote a now-classic study of Tagalog poetry.

LUMBERA joined the English Department of Ateneo de Manila University and established himself as a drama critic and leading scholar of Tagalog literature. Aside from a handful of poems, however, everything he published was in English, the medium of instruction at the Ateneo and virtually all other Philippine universities. Stirred by the wave of passionate nationalism sweeping Philippine campuses in the late 1960s, LUMBERA included more vernacular readings in his literature and drama courses. And he began, haltingly, to deliver some of his lectures in Filipino, the Tagalog-based national language. In 1970 he became chair of Ateneo’s new department of Philippine Studies and, for the first time, published his own critical essays and reviews in Filipino.

When Martial Law was declared in 1972, LUMBERA left his post at the Ateneo and went underground. Captured in 1974, he spent nearly a year in detention, frankly relishing the companionship of his like-minded detainees. Two years after his release, he was named professor in the Department of Filipino and Philippine Literature at the University of the Philippines.

Years of startling productivity followed. LUMBERA wrote and lectured prolifically on literature, language, drama, and film. He composed librettos for new musical dramas such as Rama Hari and Bayani. He published three award-winning books of criticism and, with his wife Cynthia, an anthology of Philippine literature. He moved actively in literary circles and organizations, edited journals, and contributed introductions to dozens of books written by his friends and former students. As a teacher he mentored a new generation of literary scholars imbued with his own love for the country’s rich artistic traditions and languages.

Language, says LUMBERA, is the key to national identity. Until Filipino becomes the true lingua-franca of the Philippines, he believes, the gap between the well-educated classes and the vast majority of Filipinos cannot be bridged. “As long as we continue to use English,†he says,†our scholars and academics will be dependent on other thinkers,†and Filipino literature will be judged by Western standards and not, as it should be, by the standards of the indigenous tradition itself. Discerning such standards is an important part of LUMBERA’s work. He is learning, say his students, to see Filipino literature through Filipino eyes.

In electing BIENVENIDO LUMBERA to receive the 1993 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Journalism, Literature, and Creative Communication Arts, the Board of Trustees recognizes his asserting the central place of the vernacular tradition in framing a national identity for modern Filipinos.

Lubos akong nagpapasalamat sa karangalang iginawad sa akin. Alam kong ito ay galing hindi lamang sa Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation kundi galing na rin sa lahat ng dating estudyante ko at mga kagurong naging mabulaklak ang dila nang sila’y usisain tungkol sa akin.

In 1959, I was a graduate student at an American university who had proposed topic of his dissertation approved. “Bakit hindi paksaing Pilipino? Why not a Philippine topic?†The question started a process of reeducation that was to remake my consciousness as a colonized intellectual suddenly face-to-face with nationalism.

This evening, I stand before you, a recipient of a prestigious award, simply because somebody three decades ago has the impertinence to ask: “Bakit hindi paksaing Pilipino?†This Award is awesome, indeed, for it affirms a principal tenet of nationalist literary studies, the centrality of the vast body of native-language literature in the Filipino literary canon.

Kung may nakamtang mga tagumpay ang kilusang makabayan ng dekada sesenta at setenta, ito, sa palagay ko, ang pinakapangmatagalan. Ipagdiwang natin ang pagkaahon ng Panitikang Pilipino sa kumunoy ng neokolonyal na edukasyon!