As a freelance journalist and former rural affairs editor of The Hindu, 2007 Ramon Magsaysay Awardee PALAGUMMI SAINATH took a different path. Believing that “journalism is for people, not for shareholders,” Sainath doggedly covered the lives of those who have been left behind.

Born in Chennai (formerly Madras) in 1957, Sainath chose the life of a journalist after finishing a master’s degree in history at the Jawaharlal Nehru University. “I would rather be a journalist in India than anywhere else in the world,” he once said in an interview. The rich legacy of Indian journalism explains Sainath’s mindset. After all, Gandhi and other leaders in the struggle for India’s independence had doubled as journalists and contributed to the “liberation of the human being.” As Sainath puts it, “The Indian press is a child of the freedom struggle.”

As a journalist, Sainath has been choosing beat or regular assignments on India’s millions of rural poor since 1993. Unlike the legions of journalists dazzled by the economic reforms begun in this South Asian giant in the early nineties, Sainath suspected a dark side to the philosophy of “development, Indian style,” so he decided to set out to prove it. This meant giving up a comfortable job at Blitz, a widely circulated Mumbai-based weekly where he was then deputy editor and a popular columnist, in exchange for a fellowship with the Times of India.

For the next two years, Sainath traveled the breadth and depth of India’s 10 poorest districts, or what many consider a hardship post, and reported firsthand the hunger and poverty gripping rural India on an unknown scale since its independence in 1947, the consequence of disastrous development policies.

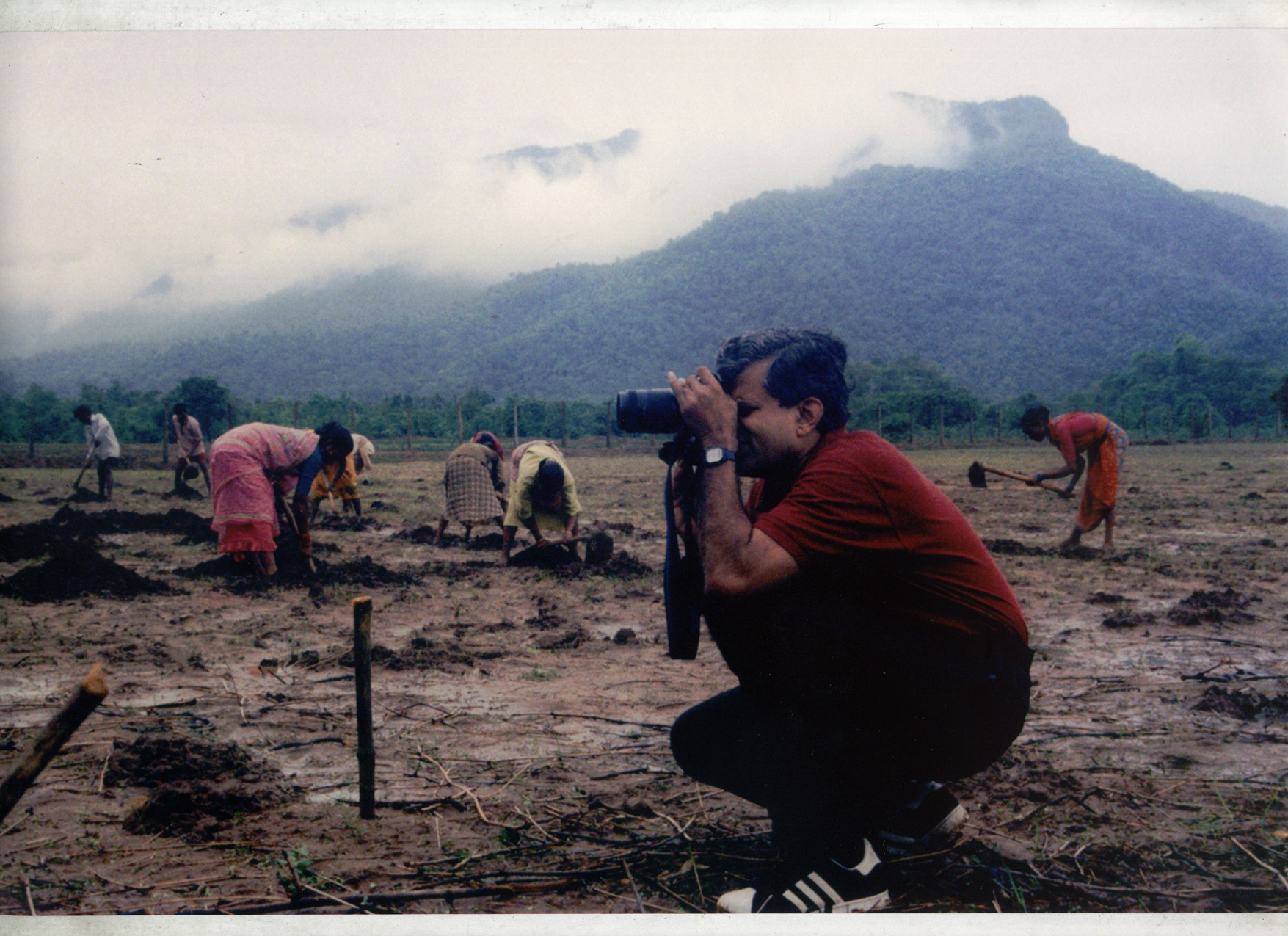

Palagummi Sainath taking photos for the exhibition in Vizianagaram district of Andhra Pradesh state.

There was no turning back for Sainath. His reportage on rural India would subsequently set off reforms in policies and programs affecting the poor—farmers, tribal people, women, and dalits or untouchables, among others. His bestseller, Everybody Loves a Good Drought, an anthology of 68 of the 84 reports he had filed as a Times of India fellow from 1993 to 1995, has become a journalism classic and required reading in universities in India, North America, and Europe, along with his many other stories on poverty and development.

“Dissident journalism” in India is not the only area that greatly influenced Sainath’s philosophy of journalism, but also the journalism industry in the United States. He firmly believes that “the best journalism has always come from dissidents.” In Sainath’s book, Thomas Paine, the 18th-century pamphleteer who advocated independence for the American colonies and the rights of man, was the greatest dissident journalist. “He practiced the only journalism worth practicing: Journalism based on a commitment to ordinary people, to very high democratic ideals, and to bettering the living conditions of people around him,” he said.

Alas, by the time Sainath ventured into newspapering, Indian journalism prevailed in the early 20th century and Paine’s brand of journalism had vanished. He discovered that the Indian media in the late 20th century was no longer “journalism for people (but) journalism for stakeholders.” Media ownership had shifted from family-owned businesses with a “sense of purpose” to conglomerates, even trusts, run by corporate CEOs who placed a premium on revenue- rather than people-driven journalism. The reportorial beats reflected the bias. There were political, ministry, business, fashion, entertainment, glamor, design and even “eating out” correspondents, but no single, full-time correspondent assigned to agriculture, housing, primary education, labor, or the social sector. A poverty or rural affairs beat was unthinkable.

At a time when hunger-related mass migrations and deaths, including suicides among peasants, were on the rise, journalists were churning out “feel-good” stories catering to the growing middle class. Stories on weight-loss clinics, the latest car models, and beauty pageants were crowding out serious journalism. Even elections coverage had morphed; its increasing emphasis on entertainment and personality was cutting into valuable space and air time for public discourse on pressing life-and-death issues.

“We’re blessed with good young journalists, and there’s also a new phenomenon—of people from non-journalistic backgrounds coming into media and bringing a completely different lens.”

Sainath wasn’t—and isn’t—one to hold back from saying what he deemed as the sorry state of Indian journalism. “The fundamental characteristic of our media is the growing disconnect between mass media and mass reality,” he has repeatedly said.

Development journalism, too, turned out to be a source of disappointment for Sainath, having failed to live up to its much-vaunted promise to put development on the public agenda. The reason: Not only had development journalists failed to see through the government or official mantra, but they had also unquestioningly accepted the lines fed to them by nongovernmental organizations or NGOs, especially those the state and the corporate sector had co-opted. On far too many occasions, journalists have been reduced to mere “stenographers,” Sainath noted. He writes in his introduction to Everybody Loves a Good Drought: “Lack of skepticism makes for bad journalism and wearisome copy.”

Sainath’s trailblazing reporting on the rural poor would upset India’s prevailing, if not faulty paradigm of journalism, and force journalists to reexamine themselves and their craft. His powerful, poignant narratives on India’s invisible hunger for the Times of India, other publications, and The Hindu, of which he has been the rural affairs editor from 2004-2014, embody his conviction that journalism must focus on the processes and not events of poverty and, just as importantly, about people and their problems. “In covering development, it calls for placing people and their needs at the center of the stories. Not any intermediaries, however saintly. It calls for better coverage of the rural political process. Of political action and class conflict, not politicking,” he said. For example, the 68 accounts in Everybody Loves a Good Drought, nearly all told in about 800 words, supply anecdotal evidence that the crisis in India’s agriculture was more the making of bad, even absurd policies, aggravated by endemic corruption, rather than of drought and other natural calamities. The stories range from tragicomic and heartrending to the against-all-odds and uplifting.

Sainath’s Everybody Loves a Good Drought offers stories of hope and courage as well by zeroing in on the survival strategies of the poor. About 4,000 women in Tamil Nadu acquire leases to stone quarries through an anti-poverty program and contribute to their village economy. Thousands of women in the same district learn to cycle, in the process acquiring independence, freedom, and mobility that help them boost family incomes.

“Lack of skepticism makes for bad journalism and wearisome copy.”

It is not only through words but also through photographs that Sainath has captured the tales of India’s rural folk, especially the women. “Visible Work, Invisible Women,” his 70-piece black-and-white photo exhibition, has been mounted across India and overseas to trumpet the unrecognized contributions of poor women to the economy. He does the photography for his stories. “I could never find a photographer to accompany me to some of the places where I go,” he said.

Bricks, coal and stone: Migrant labourers from Orissa state in a brick kiln in the state of Andhra Pradesh. The women walk barefoot in the kiln and the sand and carry hot bricks on their head.

Sainath also travels a lot—a hobby that he still continues to do to this day, spending between 270 and 300 days a year in India’s rural interior to document what he calls “basic failures” in Indian society: land reform, social issues, caste, gender, regional development.

If there is one thing Sainath is equally firm about, it is his refusal to take corporate or government funds to finance his reporting. He would rather dip into his own pocket. Sainath recently told the online publication India Together that he intends to use the prize money that will come with the Magsaysay Award to pursue two dream projects: an archive of rural India—People’s Archive of Rural India which was launched in December 2014—and a series on the last remaining freedom fighters of India.

It is likewise Sainath’s dream to see more Indian journalists engage in the pro-people journalism he loves, and has initiated the process. The royalties from Everybody Loves a Good Drought have funded the Countermedia Prize of Excellence in Journalism which recognizes outstanding work in rural reporting. He has taught journalism at universities in India and overseas, as well as run journalism workshops directly in the villages where he hopes to inspire writers to become agents of change.

In 2007, SAINATH was elected to receive Asia’s premier prize and highest honor, the Ramon Magsaysay Award for “his passionate commitment as a journalist to restore the rural poor to India’s consciousness, moving the nation to action.” His other noteworthy awards include New York’s Harry Chapin Media Award, Amnesty International’s Global Human Rights Journalism Prize, and the European Commission’s Lorenzo Natali Prize.

Will Indian journalism change for the better? Sainath is optimistic it will. In an interview after winning the Magsaysay Award, he said: “We’ve got history on our side—180 years of it in this country. Twenty years of trivialization is a minor period in that larger history. We’re blessed with good young journalists, and there’s also a new phenomenon—of people from non-journalistic backgrounds coming into media and bringing a completely different lens.”