In a world absorbed in scientific and material ventures that even lead men to the moon, we easily lose sight of that greatest frontier in man himself. On this centenary of Mahatma Gandhi’s birth, the Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement, led by A. T. ARIYARATNE in Ceylon, reassuringly confirms man’s response to challenges of the spirit.

A Sinhala and a Buddhist, ARIYARATNE first acted against injustice while a college student. Sharing his pocket money with an impoverished, old woman, he learned greedy middlemen paid her too little even for food, though she spun coconut coir 10 hours a day six days a week. Undeterred by a stabbing intended to thwart him, he organized the Coir Workers Cooperation Society that improved the spinners’ lot and still flourishes.

Seeking national concern for the poor, ARIYARATNE investigated all of Ceylon’s then 20 odd political parties, the responsible government agencies, and religious groups, but found scant promise of social change. It was from study of the works of Acharya Vinoba Bhave, Gandhi’s leading disciple, that he became imbued with the idea of voluntary service based on truth, non-violence and self-denial.

Remembering Bhave’s admonition that without personal sharing any movement would prove a delusion, ARIYARATNE began in Ceylon by inviting donation of labor from colleagues at Nalanda College, where he was teaching. From ancient Ceylonese tradition he evolved the concept of sarvodaya shramadana, meaning to share one’s time, thought and energy for the welfare of all.

In 1958, 75 teachers and students of the College went to the outcast village of Kanatolowa. Working with villagers to sink wells, dig latrine pits, clear home gardens and start a school, these volunteers gave the “untouchables” their first sense of human dignity through shared generosity. Requests from other villages followed for similar Shramadana camps where volunteers concentrated their labor on weekends and during vacations upon specific “felt needs” that could be accomplished with donated resources.

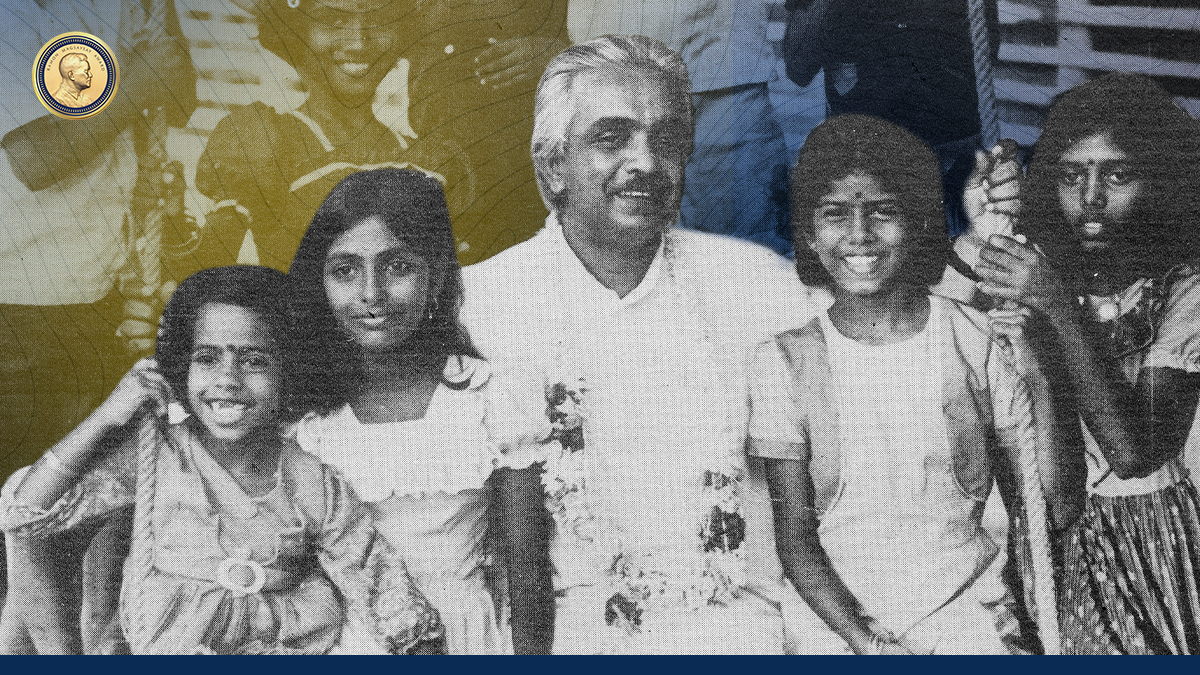

Under ARIYARATNE’s magnetic leadership, Sarvodaya Shramadana became the largest national voluntary movement. Members had only to subscribe to “service for all” and give seven days a year. Other college and university groups, Buddhist monks, doctors, government and factory employees and industrialists joined the crusade. Learning the real needs of their country, these volunteers helped eradicate distrust resulting from caste, race, creed and party politics. Self-confidence generated in villagers produced sustained improvement efforts.

After five years, the Movement acquired legal status as the Lanka Jatika Sarvodaya Shramadana Sangamaya. Now an “approved charity” with a small professional staff and its resource of 75,000 trained, young volunteers throughout the country, the Movement is honoring the Gandhi Centenary by seeking to transform 100 villages with its message of spiritual ennoblement and volunteers targeted on projects discriminatingly selected and planned.

In electing AHANGAMAGE TUDOR ARIYARATNE to receive the 1969 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Community Leadership, the Board of Trustees recognizes his founding and inspired guidance of the Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement, combining voluntary service in meeting village needs with an awakening of man’s potential when he cultivates his best instincts.

It is with deep humility and renewed faith in the service of humanity that I rise on this memorable occasion to deliver this brief response. This is an honor you have given to my country, to the Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement of which I am a humble worker, and above all an honor given to chose simple village people who responded to our call of “love and service.” I am only a medium chosen by destiny to assist the Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation to carry the spirit of that great leader, the late President Ramon Magsaysay, into the minds and hearts of my own common people—for it was for the emancipation of the common man that he lived and died.

Great men of the caliber of Ramon Magsaysay do not belong to one country or one period or one generation. They are social phenomena that suddenly appear and disappear like flashes of lightning in darkness and show us the path. They belong to the entire universe and eternity. Lord Buddha says “Rupan jeerathi maccanan—Nama goththan na jeerathi”—which means while all that is mortal in us decays our noble thoughts, words and deeds will live long after our physical remains are gone. The true greatness of a man is known only by the way his fellowmen hold him in esteem after his death. Judging from the name he has left behind to be honored and perpetuated in this manner, I am sure he must now be among the divine. May he bless us all in our endeavors to serve our fellowmen, particularly those that are considered the lowest—the lowliest and the lost.

I believe the Foundation has elected me for the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Community Leadership on the basis of the external manifestations of my behavior in that particular field. Therefore, it is my duty to place before this august assembly some of my inner thoughts that motivated my external behavior.

In the culture in which I was brought up I was fascinated from my childhood by certain thoughts the implementation of which, however, was postponed by that same culture to the next life. “Peetho bhavatu lokocha”, meaning “may all beings in the universe be well and happy”, was one such thought. Working for a nobler ideal than the ideal of the greater good of the greater number became a passion in my life. Mahatma Gandhi and Acharya Vinoba Bhave called this thought, the welfare of all, by the Sanskrit word sarvodaya.

For the awakening of all in society we have to awaken ourselves first. Again my own Buddhist culture showed me four noble goals towards which every individual should strive. The first is loving kindness, or metta as we call it. As a good mother loves her one and only child and protects him at the risk of her own life we are taught to love and protect all living beings. Secondly, we are taught to cultivate kanuna, or compassion, which motivates us to go in search of those who suffer and help remove the causes which have brought upon them that suffering. Thirdly, we are taught to train ourselves to take altruistic joy in others’ happiness. We call this muditha. Fourthly, to educate oneself in upekkha, or equanimity, which gives one emotional balance to take fame or blame, profit or loss, success or failure with detachment and patience. These four qualities are called divine abodes because they elevate the follower to divine levels. It is this philosophy of life that motivated me for this silent mission which you have adjudged worthy of honor.

These are not impractical idealistic thoughts that have no relevance to the modern scientific and technological world. Modernity is not determined by time. It is determined by our attitudes and outlook to life and living. These thoughts we translated into practical application to bring about significant changes in the grass-roots of our society — changes for the better among our rural communities which are the foundation of our culture, freedom and human dignity. And wasn’t it our revered Ramon Magsaysay himself who said that “democracy should start from the grassroots?”

The technique we adopted to translate thoughts into action was a call to all to share their ?time, thought and energy? in the service of their fellowmen. We called it shramadana. Sharing (dana), compassionate speech (priya vacana), constructive activity (arthacharya) and equanimity (samanath-matha) are the four salient features of shramadana.

These thoughts and action in their own small way are laying a strong spiritual and material foundation for rebuilding a new Ceylon — a new Sri Lanka — where I assure you science and spirituality will be harmonized and the island deserve once again to be called Dharmadweepa — The Island of Righteousness. Here and now I declare in the name of that great leader, the Lord Buddha, that every cent of this monetary award and every element of personal recognition that you have given me today will be utilized for this noble end. For I believe as he believed that “you can find yourself only to the extent you can lose yourself.” Lose yourself in what? Lose yourself completely and totally in the service of your fellowmen to free them from the causes of all suffering; namely, greed, ignorance and hatred.

Related Articles

A Tribute to 1969 Ramon Magsaysay Awardee A. T. Ariyaratne

Apr 16, 2024