YOUK CHHANG, a survivor of Khmer Rouge genocide that killed at least 2 million Cambodians, has devoted his life to preserving its historical memory for judicial redress, national reconciliation, and collective healing.

DC-Cam painstakingly assembled over a million documents as evidence in Cambodia\u2019s War Crimes Trials. The public witnessed these trials and had access to all DC-Cam\u2019s digital files.

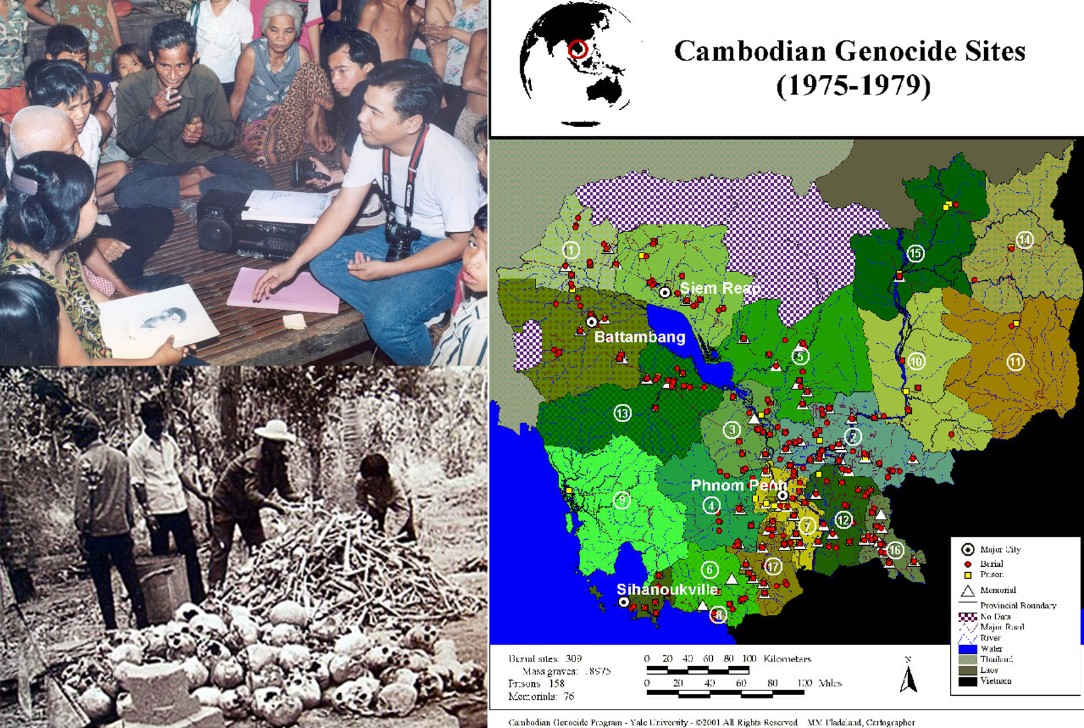

DC-Cam has been able to produce digital mapping of over 23,000 mass graves throughout Cambodia\u2019s \u201ckilling fields,\u201d using these to support its educational programs on genocide, transitional justice and human rights.

YOUK says: \u201cI do this for my mother who suffered… I want her to be a free woman, not to carry all the tragedy in her heart and in her life.\u201d He has widened this deeply-felt commitment into the work of remembrance, justice, and healing for all Cambodians.

The five-year Cambodian genocide of 1975-79, that caused the death of at least two million Cambodians, is one of the most horrific episodes in the long, dark history of crimes against humanity. It is imperative to the cause of justice that this horror is not forgotten. YOUK CHHANG, one of its survivors, has devoted his life to the monumental task of documenting and memorializing the genocide to serve the aims of judicial redress, national reconciliation, and collective healing. More importantly, his work assures that the past is truthfully preserved for present and future generations so that it will not be distorted or ever repeated.

Born in Phnom Penh, YOUK was fourteen years old when his family was forced out of their home by Khmer Rouge operatives to work like slaves in a rural commune. He saw his family reduced to extreme privation; was himself tortured and detained; even worse, YOUK suffered the trauma of the death of his father, five of his siblings, and nearly sixty of his relatives. Able to escape across the Thai border to freedom at the age of seventeen, he found his way as a refugee to the United States. Years later, he would earn a graduate degree in political science and chose to return to Cambodia when civic order had been restored, enrolling in the human rights and democracy training programs of the International Republican Institute and the UN Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC).

YOUK found his life-long mission in 1995, when the Yale University’s Cambodian Genocide Project engaged him to head its Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam), charged with investigating and documenting Khmer Rouge atrocities. Two years later, DC-Cam became an independent institute, directed and operated entirely by Cambodians. As its executive director from 1995 to the present, YOUK expanded DC-Cam’s work beyond documentation in aid of the Khmer Rouge War Crimes Trials that began in 2009; he pursued the broader task of promoting “memory and justice as the critical foundations for the rule of law and genuine national reconciliation.â€

The scope of this work has been immense, arduous, and painfully difficult in Cambodia’s transitioning, polarized society. Despite the destruction, loss, or absence of records, DC-Cam was able to collect and assemble over one million documents, providing over half of these as evidence in the war crimes trials. They digitized these documents for online public access; produced digital mapping of over 23,000 mass graves in Cambodia’s “killing fieldsâ€; excavated samples of human skeletal remains for forensic examination; conducted interviews with over 10,000 persons, both victims and perpetrators; implemented research, publishing, and educational programs on genocide, transitional justice and human rights; and promoted public participation in the whole process. Yet YOUK’s work is not only turned towards the past, it also looks to Cambodia’s future: he recognizes that preserving and understanding the past must serve as a powerful safeguard against all those who may seek to distort or erase it.

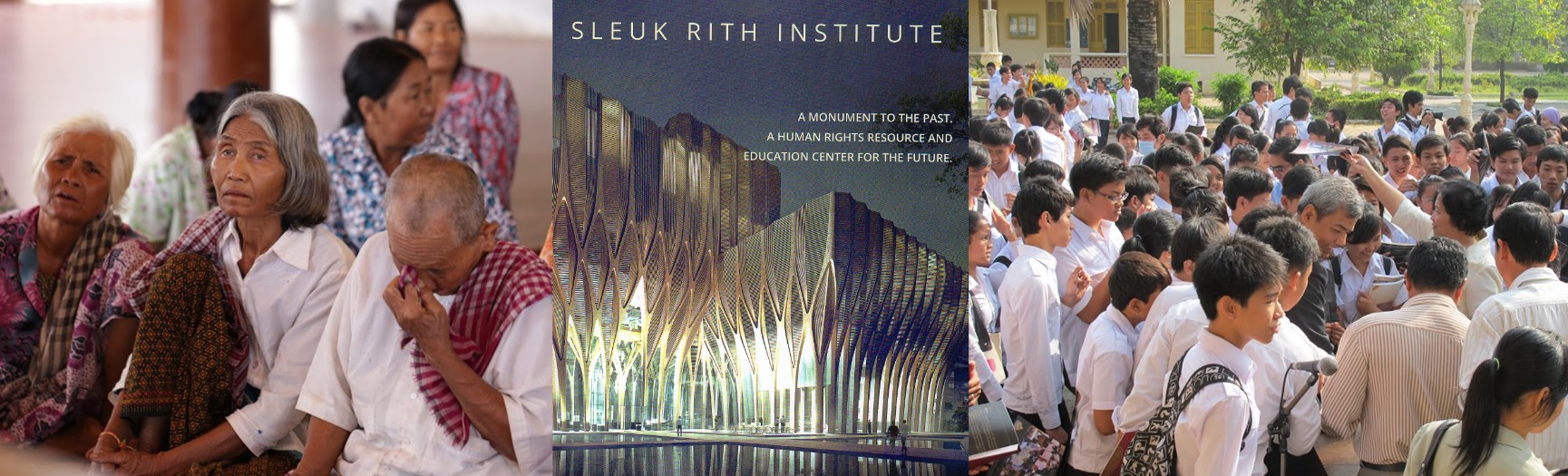

Today, YOUK is engaged in building the Sleuk Rith Institute, an ambitious project which will house a museum, archives and library; a research center; and a graduate program on crimes against humanity to sustain what DC-Cam has accomplished and serve as a resource center for a world deeply scarred and still threatened by genocide.

All this is not an abstract mission for YOUK but one that is profoundly personal. Of his mother, who, borrowing five US dollars, pushed him to flee Cambodia and whom he would only see some twenty years later, he says: “I do this for my mother who suffered… I want her to be a free woman, not to carry all the tragedy in her heart and in her life.†It is a deeply-felt commitment he has widened into the work of remembrance, justice, and healing for all Cambodians.

In electing YOUK CHHANG to receive the 2018 Ramon Magsaysay Award, the board of trustees recognizes his great, unstinting labor in preserving the memory of the Cambodian genocide, and his leadership and vision in transforming the memory of horror into a process of attaining and preserving justice in his nation and the world.

Salamat Po. I am humbled by this most prestigious award. In receiving it, I am reminded of a thought I often have as a survivor: “If you have survived genocide, you are blessed in many ways. You can begin again. You find a place to live, get a job, make friends, and start a family. But physical survival is the easy part. You can also be unlucky in just as many ways. Genocide breaks you. Your heart aches from losing the people you loved. You are haunted by your memories. You feel guilt at merely surviving when so many died. And worst of all, you can lose hope.â€

I am reminded every day by survivors and the people who advocate on their behalf, to not lose hope. I take heart in the relentless strength of survivors and the heroic, kind-hearted people who help them. This award is a reminder, on behalf of my mother and all mothers in Cambodia who have survived the genocide, of the kindness of the Filipinos. The Filipinos opened their country to Cambodian refugees in the wake of the Khmer Rouge regime’s collapse in the 1980s. The Philippine government and people, along with other countries including the United States, rose to the occasion in helping us. In receiving this award, I want to take the opportunity to thank the Philippines for their kindness back then. Your help to the Cambodian people was a shining example to not give up hope.

I also want to say that it is important to remember the mistakes of the past. We must remember mistakes as a decisive act at all levels of society from individuals to communities and governments. Remembering mistakes is not easy because it requires us to consciously accept additional pain in the present so that our children will not relive our mistakes in the future. But this is the pathway to justice. Justice will always begin and end with the duty of memory.

Again, salamat po, mula sa kaibuturan ng aking puso.