- Thirteen years ago, Jesuit JOHN VINCENT DALY, a Sogang University philosophy professor, decided to learn how the poor viewed life by moving into Cheong Kyei Cheon, a Seoul slum.

- Three years later Yahng Pyeong Dong was classified for redevelopment. Little compensation or concern for their rehousing was vouchsafed the residents. Fifteen families approached DALY and JEI for help.

- They have established the Korean Catholic Research Institute of the Urban Poor to aid slum dwellers in learning their legal rights and correcting injustices such as unwarranted or unrecompensed evictions.

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes their education and guidance of the urban poor to create vigorous, humanly sound satellite communities.

When South Korea’s effective modernization began a quarter of a century ago, it was geared to a manufacturing for export drive that stunned the trading world with efficient production of low cost goods. Disciplined laborers working harder, often for less, than anyone else in East Asia, were a key to this success. Unlike in Japan and Taiwan, where after World War II rural progress came first, in Korea villages felt the sweeping winds of change only a decade later. Hence seekers for employment and opportunity flocked to the cities, making Seoul one of Asia’s dozen largest cities and inevitably creating massive slums where social services lagged behind the need.

Life in a slum, though devoid of most amenities, still allows a sense of family warmth and home. Networks of relatives and co-workers cushion harsh outer realities. Now even this make-do haven is threatened by booming urban land values and both public and private redevelopment schemes that mean misery to evicted slum dwellers.

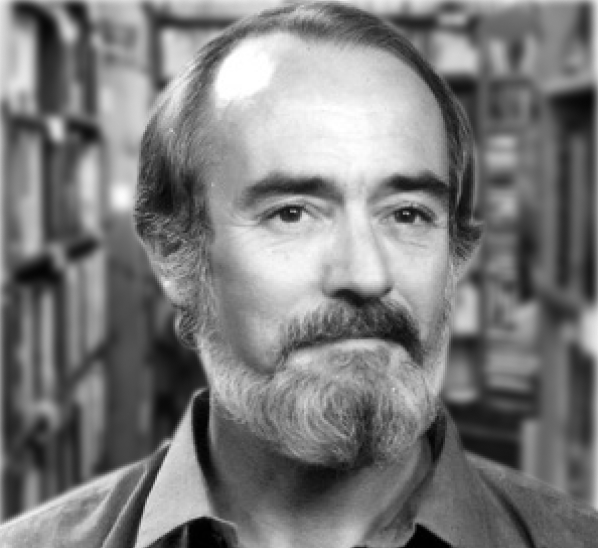

Thirteen years ago, Jesuit JOHN VINCENT DALY, a Sogang University philosophy professor, decided to learn how the poor viewed life by moving into Cheong Kyei Cheon, a Seoul slum. There he met PAUL JEONG-GU JEI, recently expelled from Seoul National University for leading demonstrations. Their first partnership in community concern lasted less than a year. JEI, after readmission to the university, was soon jailed for 11 months for antigovernment activities. Not long after he was released he and DALY decided to open a community center in two rented rooms in Yahng Pyeong Dong slum. Convinced that outside problem solvers tend to impose their perceptions, the two sought to be catalysts fostering community-determined change.

Three years later Yahng Pyeong Dong was classified for redevelopment. Little compensation or concern for their rehousing was vouchsafed the residents. Fifteen families approached DALY and JEI for help.

With US$100,000 from MISEREOR, the German Catholic Social Aid Fund, and other monies from abroad, the two were able to purchase a small plot of land 12 kilometers southeast of Seoul only days before the eviction was to be carried out. DALY, JEI, and the committee of slumdwellers which they had helped create, expected fewer but finally accepted 170 families. In May 1977 all but 20 of the families moved into tents on the new site and joined in building the village of Bogum Jahri, the Place of Happiness. With three skilled members as construction supervisors, and enthused by interdenominational prayer, the newcomers completed construction of the buildings by November 1977, and the sewage system for the 170 houses was finished by the onset of winter cold in December.

From such beginnings emerged a practical system for building housing at the equivalent of US$166 per pysong, or 3.3 square meters, largely with self-made construction materials which are one-third the cost of commercial materials. The second village was Han Dok and the third MokWha. A community center was constructed within walking distance of all three.

DALY, who was born in Philo, Illinois 51 years ago, has made South Korea his home for 26 years. Both he and his partner,JEI, who was born in 1944 in South Kyong-sang province, have become participants in the daily struggles of the homeless poor. They have established the Korean Catholic Research Institute of the Urban Poor to aid slum dwellers in learning their legal rights and correcting injustices such as unwarranted or unrecompensed evictions. The two are also attempting to prove that a rich cultural heritage can be retained and enhanced by the most disadvantaged, provided there is effective community organization and local leadership.

In electing Father JOHN VINCENT DALY and PAUL JEONG-GU JEI to receive the 1986 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Community Leadership, the Board of Trustees recognizes their education and guidance of the urban poor to create vigorous, humanly sound satellite communities.

Because of the continuing spirit of President Ramon Magsaysay manifested through the Foundation and the awards named after him and the trustees and staff we have been privileged to meet in the last two days, it is a great honor to receive the Magsaysay Award. But it is an even greater honor to receive it in 1986, the year when the people of the Philippines—and the spirit at work within them—added a new chapter to human history, giving hope and courage and light to millions of ordinary “little people” all over the world.

You may wonder what I have hanging around my neck. It is a list of the names of the 135 families who rent rooms in an area of Seoul called Sang Kyei Dong who have been resisting eviction because they have no money and they have nowhere to go. Because they are delaying the construction of new high-rise apartments which will bring a $20-30,000,000 profit to someone, on June 26 of this year the 60 or 70 women who happened to be home that day were severely beaten up. Some of them were swung about in the air until they lost consciousness; their furniture and houses were half-destroyed; some of their children were picked up and tossed through the air onto piles of debris. This went on for about five hours while some 300 riot police just stood by. When the fighting ended the police arrested the 60-70 women who had been beaten up.

I lived with these families most of July and tasted, a bit, their fear and anxiety at not knowing when the next attack would come. But I tasted a lot more their courage and dignity.

When I left Korea onJuly31 these people gave me this gift with their names on it, saying, “we want to be with you.” They are. They are here on this stage today. In fact, in my mind, there are many people here right now accepting this award: my mother, father, brother and sister and the rest of my family; Cardinal Steven Kim; the staff of organizations like MISEREOR (Federal Republic of Germany) and CEBEMO (Netherlands); the rest of our Bogum Jahri Team; the people of our three resettlement villages—Bogum Jahri, Han Dok, MokWha; the courageous people of areas like Mok Dong, ShinJeong Dong, Sa Dahng Dong, Oh Kum Dong, Ha Wang Shim Ni and Sang Kyei Dong; and the 3,000,000 people who will be made homeless if the government carries out its schedule of “redeveloping” 230 areas in Seoul by 1990.

I accept this award in their name. And I pray to God that this gold medal will give them the light to recognize their own infinite value so that they will have the tremendous courage they will need to continue to fight for their rights as human beings—to fight not out of hatred but out of love—love for themselves, love for their children and grandchildren, love for the people, culture and future of Korea.

I thank all of you—Mrs. Magsaysay, the trustees and staff of the Magsaysay Foundation—from the bottom of my heart for doing the one thing—in a sense the only thing—the urban poor of this world are longing and crying for, the thing they need most of all: you have recognized them as human beings come.

I only hope that your courage in taking this stance will prick the consciences of many governments and city planners and nudge them to take a second look at the urban poor, to see them not as faceless and troublesome statistics which must be removed to make room for “development,” not as stray dogs or pieces of furniture which can be driven away or moved around whenever someone has a chance to make a few dollars, but as people, as citizens and as human beings who have every right to a little bit of ground under their feet end a roofover their heads.

People’s power, Philippine style, shows us all that that day can come.