- GHOSH authored the popular columns in the literary weekly Desh and in Calcutta’s largest vernacular daily, Ananda Bazar Patrika, of which he also became senior editor.

- With rare courage he satirically portrayed in his News Commentary by Rupadarshi the agony of West Bengal as the Naxalites—a Maoist terrorist movement—from 1969 to 1971 sought power through widespread murder.

- In best-selling fiction written before and after his incarceration he has illuminated the underlying human dilemma of West Bengal, of a talented, emotional people sorely riven by deep-seated religious and political differences.

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes his compassionate crusade through art and activism to claim for tribal peoples a just and honorable place in India’s national life.

Becoming and remaining an honest, effective and forthright writer in developing countries is a difficult and hazardous career. It is not only governments, sensitive to their local and international images, who try to curb and influence what is printed and broadcast. Every political and economic pressure group jealously seeks to foster its case. Publishers often are financially shaky and writers are commonly underpaid; both face the quandary of how to survive and be true to their profession.

Since India’s independence 34 years ago, Calcutta and the hinterland of West Bengal have been perilous yet challenging arenas for writers. Heirs to the great Bengali cultural and literary tradition enhanced by giants like Rabindranath Tagore, they feel a deep obligation to pursue the finest artistic and intellectual standards. Yet traumatic social pressures make for a modern violence—reminiscent of the ancient terrorism of the thuggees—of which the chroniclers become targets.

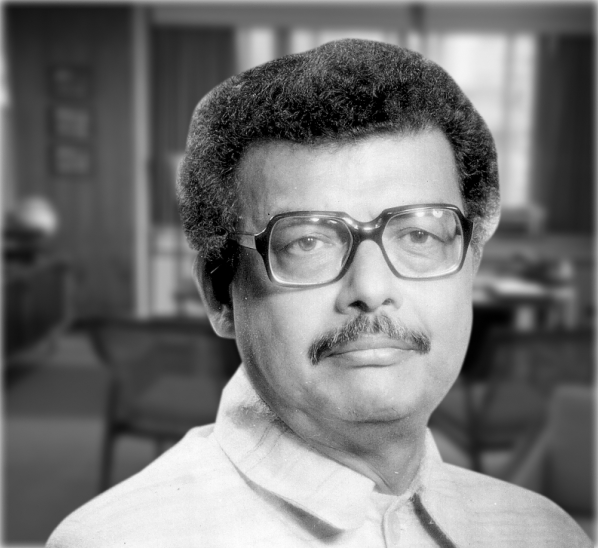

GOUR KISHORE GHOSH, born 58 years ago in the village of Hat Gopalpur, now in Bangladesh, grew up in this environment of upheaval. His father was an idealist of modest means who took in disabled destitutes from the streets and deserted his family when GHOSH was 18. To provide for his mother and four younger sisters, GHOSH worked as an electrician, fitter viseman, air raid rescue mate, petty timber trader, restaurant boy, manager of a wandering dance troupe and a trade union organizer. Attending college briefly in between jobs he passed the Intermediate Examination in Science in 1945. Three years later he became a proofreader on a short-lived weekly literary magazine. From an interim job as a border customs clerk he joined a new daily newspaper where his distinctive writing style earned him promotion to editor of two feature sections.

GHOSH went on to author popular columns in the literary weekly Desh and in Calcutta’s largest vernacular daily, Ananda Bazar Patrika, of which he also became senior editor. With rare courage he portrayed in sharp satire in his News Commentary by Rupadarshi the agony of West Bengal as the Naxalites—a Maoist terrorist movement—from 1969 to 1971 sought power through widespread murder. When the Naxalites notified GHOSH he would be assassinated unless he apologized, he replied in print with heavy sarcasm and kept on writing. In turn, he defended the terrorists’ right to legal due process when the government retaliated with excessive violence.

After “the emergency” was imposed upon India in 1975, GHOSH shaved his head and wrote a symbolic letter to his 13 year old son explaining his act of “bereavement” over the loss of his freedom to write. Published in Kolkata, a Bengali monthly, this letter caused his arrest, was widely circulated through the underground and became a classic of protest. GHOSH smuggled from prison two other letters on abuses of authoritarian rule before, in his cell, he suffered a third heart attack. His political thesis was: “People remain apathetic to any form of government. Democracy is a word rather than a political fact. We have to take more responsibility to keep democracy alive, especially in an underdeveloped country with masses of poor.” In best-selling fiction written before and after his incarceration he has illuminated the underlying human dilemma of West Bengal, of a talented, emotional people sorely riven by deepseated religious and political differences.

Although reinstated as a senior editor of Ananda Bazar Patrika after “the emergency” ended and he had recovered from his illness, GHOSH decided that to instill the values essential for future generations of Indians demanded a more focused and higher caliber of journalism. From this conviction and in collaboration with like-minded associates came Aajkaal (This Time), the recently launched Bengali daily he edits. His wife, two daughters and son share his beliefs and his spartan living. It has not been an easy path, but it is the choice for this journalist who would enhance the quality of Indian society which is being shaped by today’s hectic events.

In electing GOUR KISHORE GHOSH to receive the 1981 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Journalism, Literature and Creative Communication Arts, the Board of Trustees recognizes his sagacious courage and ardent humanism in defense of individual and press freedom amidst pressures and threats from left and right.

That a man like me would be selected as the recipient of a prestigious award like the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Journalism, Literature and Creative Communication Arts, and that I would come and stand before you in a resplendent function like this, was beyond my imagination. My respect for man has grown deeper with experience that ceaseless preaching for human freedom, for doing away with all the fetters that prevent the full and free development of the infinite creativity latent in man, not only brings as its reward pain, suffering and humiliation, but may also have such a satisfying fulfillment as this award. In the world of man, and only in the world of man, can such diametrically opposite things happen. Our poet of whom all of you must have heard, Rabindranath Tagore, was one of the greatest of humanists whose whole life was devoted to understanding the wonder that is man. A line of a song of his comes to my mind in this gathering. It says, “He wields the sword with one hand while with the other he gives benediction.”

In different countries of the world today, so many things of opposite nature are happening to and about man. On one side we find hatred and fear and attempts to fetter man. At the same time, we find spontaneous, irresistible expressions of man’s love and affection for fellowmen. We are filled with awe when we know that these opposites are true at the same time. In Tagore’s language again, “He wields the sword with one hand while with the other he gives benediction.”

It is not only an Indian poet who had this realization. Other greet men in other lands, too, became aware of these conflicting and opposite trends in man from their personal experiences. A great son of the Philippines, Ramon Magsaysay, was such a personality who realized that to be free is human, because man is essentially creative and freedom is the fountainhead of his creativity. Those who have studied his life and work, are fully aware that nothing was more priceless to Ramon Magsaysay than the freedom of man. His own life is the greatest testimony for the fact that an environment of freedom is the sine qua non of the inflorescence of man?s creative genius.

I said at the very outset that the Ramon Magsaysay Award is a prestigious one. Wherein does its prestige lie? Is it in the money that it carries? The amount of money, no doubt, adds to the value of an award, but does not contribute much to increasing its prestige. It is the name of Ramon Magsaysay, after which the award has been named, that has given it dignity and prestige. Magsaysay fought many a battle to restore unto man his natural dignity. And it is this that endows his name with magnetic attraction. It is this that has enabled the award associated with the name of Ramon Magsaysay to create such a powerful attraction over Asia. It is an attraction of love, of affection, of an ever-widening camaraderie.

Love and affection and camaraderie are also bonds. They are family bonds, not a bondage imposed by the sword. Man never wants to accept the bondage forced by the sword, but he comes forward gladly and willingly to accept the bond of kinship. In my own country I did defy the bondage that is imprisonment. But I have come forward joyfully to accept the bond of love with the Philippines. This is no individual characteristic of mine. It is the universal characteristic of man. That our egos often obstruct realization of this simple and self-evident truth is the tragedy of human society.

As an Indian and an ardent lover of this beautiful world, I bring to you, the Trustees, to your people and to my fellow Awardees, the tenderest love that overflows my heart and that of my beloved wife for giving us this opportunity of becoming your friends and kin; to be one of you. Please accept this offering of ours and make us thankful.