- IWAMURA undertook his medical training at Tottori University School of Medicine and, in 1958, joined its faculty as an associate professor.

- IWAMURA became a “barefoot doctor,†striking out on foot and on horseback into the mountain fastnesses where many Nepalis dwelled without benefit of medical services and where tuberculosis was pandemic.

- In 1980 IWAMURA founded the Peace, Health, and Human Development Foundation (PHD) to bring grass-roots community leaders from Nepal and Southeast Asia to Japan for technical training.

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes his heeding the call of the true physician in a lifetime of service to Japan’s Asian neighbors.

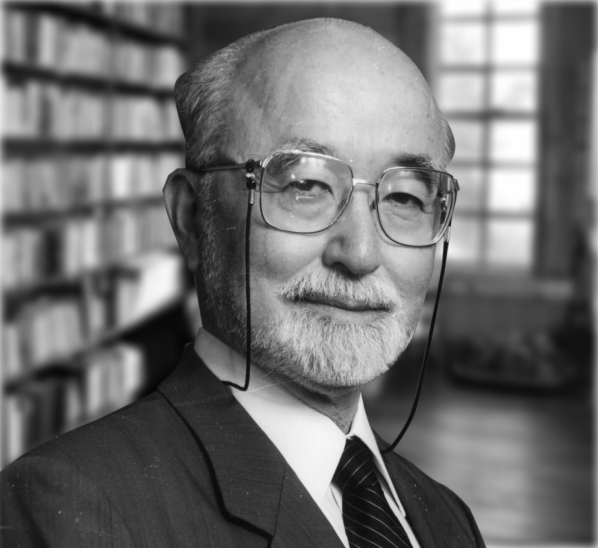

On the morning of August 6, 1945, eighteen-year-old NOBORU IWAMURA was busy conducting an experiment in the laboratory of the Hiroshima Institute of Engineering and Technology when the atomic bomb exploded just 1.2 kilometers away. Heavy cement walls collapsed over him. Three days later rescue workers found him alive beneath the debris. Of his classmates, only he survived. Contemplating the loss of his friends and the miracle of his own survival, IWAMURA resolved to become a doctor and to live his life for others.

IWAMURA undertook his medical training at Tottori University School of Medicine and, in 1958, joined its faculty as an associate professor. In 1960 he applied to go abroad with the Japan Overseas Christian Medical Cooperative Service. With his wife, IWAMURA spent the next eighteen years in Nepal. Working at first in the city of Kathmandu, he learned that many of his patients reached the hospital after trekking great distances and, all too often, only when their diseases were already fatally advanced. Why should sick people imperil themselves trying to reach me, he wondered, when I, a healthy doctor, can go to them?

IWAMURA became a “barefoot doctor,†striking out on foot and on horseback into the mountain fastnesses where many Nepalis dwelled without benefit of medical services and where tuberculosis was pandemic. In time he came to understand the relationship between the sickness of villagers and their poverty end ignorance. IWAMURA began experimenting with public health and livelihood projects. In doing so, he encountered a cardinal truth of rural development: “Uplift†programs driven solely by outside donors and specialists are bound to fail. Only when such efforts are geared toward self-reliance and when these are led by dedicated people from within the communities themselves do they truly succeed and endure.

In 1980, having returned to Japan, IWAMURA joined the International Center for Medical Cooperation at the Kobe University School of Medicine. From 1985 to 1987 he led a Japanese government team assisting in primary health care in Thailand. By this time IWAMURA had traveled throughout Asia, Africa, and Latin America and discovered the ubiquity of the sort of poverty he had first encountered in Nepal. Yet to IWAMURA, the Japanese seemed to be enjoying lives of abundance without being aware of their country’s relationship to its poorer Asian neighbors, or its dependence upon them. Calling upon the insights of his years in Nepal and Thailand, he began guiding the philanthropic instincts of his fellow Japanese to focus on urgent needs abroad, and on modest but practical ways in which these needs can be met.

In 1980 IWAMURA founded the Peace, Health, and Human Development Foundation (PHD) to bring grass-roots community leaders from Nepal and Southeast Asia to Japan for technical training. And in 1985 he established the International Human Resources Institute to sponsor young rural development workers for their master’s degrees in Community Development at the University of the Philippines in Diliman and Los Banos. IWAMURA takes a personal interest in choosing students for the program, prizing above all those candidates who are committed to carry on in community work and who possess a missionary spirit.

Fearing the genetic consequences of the nuclear blast, the Iwamuras chose to have no children of their own. While in Nepal, however, they raised and educated twelve Nepali orphans. These children are grown now. And it is with them, each year in Nepal, that 66-year-old IWAMURA celebrates Christmas.

In electing NOBORU IWAMURA to receive the 1993 Ramon Magsaysay Award for International Understanding, the Board of Trustees recognizes his heeding the call of the true physician in a lifetime of service to Japan’s Asian neighbors.

To receive this award is the greatest honor. I feel very lucky.

Many years ago I was sent by the Japan Overseas Christian Medical Service to Nepal. For eighteen years, I worked among the rural people there; I treated their sick, learned their culture, and set up grassroots programs to control tuberculosis in the most remote villages.

By working closely with these rural people, I came to see that disease and poverty were linked in a vicious circle that enlarged the gap between rich and poor. And I came to see that, in poor countries, this same vicious circle often undermined the stability of the political order and thus caused even more misery. Over the years, I observed this not only in Nepal but in several other countries in Asia and the Third World.

How can this hateful chain of poverty, disease, and disorder be eliminated? I asked myself this question. And I posed it to others such as Dr. Krasae Chanawongse of Thailand and Dr. Juan Flavier of the Philippines. It seemed to me—to us—that donations of money and materials to poor people did not get to the heart of the problem, especially when these donations were channeled through governments and large aid-giving agencies. The real solution to improving living conditions and livelihoods among Asia’s rural poor was self-reliant development. Individuals and communities had to learn to act for themselves. And for this to happen, effective and committed community leaders were indispensable.

This is why, in 1985, I founded the International Human Resources Institute (IHI) in Tokyo. Since then, IHI has been providing promising youths from Nepal, Thailand, Japan, and the Philippines the opportunity to develop themselves as community leaders. We help them through advanced training at two branches of the University of the Philippines—the College of Social Work and Community Development in Diliman and the College of Agriculture in Los Banos—as well as at the International Institute of Rural Reconstruction in Cavite. During two years of living and studying together, the IHI Fellows also share their cultures, habits, and ways of life with each other.

I am very happy to receive this award in the presence of the IHI Fellows who are with us today. It is my wish to donate the stipend from this award to support and further the activities of the International Human Resources Institute.