- As a young graduate at the time of independence from Britain and partition of the subcontinent, he threw himself into organizing relief for destitute refugees created by partition.

- Later JAIN helped Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay organize the Indian Cooperative Union and applied its principles to the handicrafts industry.

- JAIN became a sage and independent-minded expert on development, applying unique organizational skills to wed theory to practice.

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes his informed and selfless commitment to attack India?s poverty at the grass-roots level.

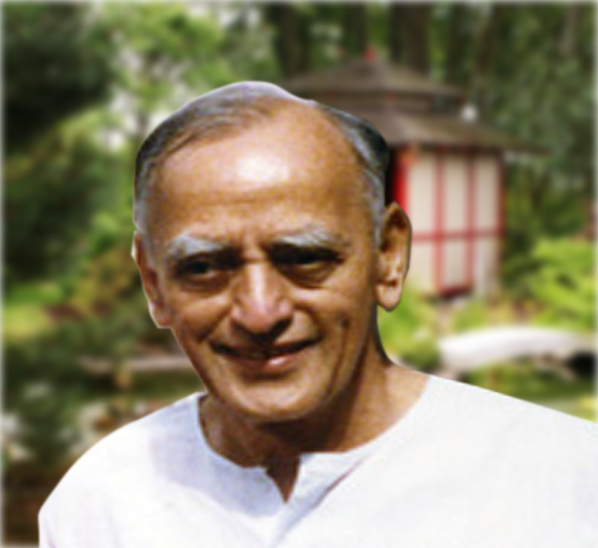

As Asia’s governments grow and assert themselves against national diversities and pluralism, benefits earmarked for economic development often bypass the needy in favor of bureaucrats and those already affluent. Observing this, LAKSHMI CHAND JAIN rejects the assumption that profound socioeconomic problems can be solved best through the machinery of the state. In his view, democratic village associations and voluntary agencies are better catalysts for rural advancement and social change. Softly and urgently, he insists that people who are alienated from the task of development will also be denied its fruits.

Born in 1925, JAIN was a child of India’s struggle for justice and dignity. As a young graduate at the time of independence from Britain and partition of the subcontinent, he threw himself into organizing relief for destitute refugees created by partition. By helping introduce cooperative societies for farming and cottage industries into rehabilitation camps, he instilled self-reliance and hope.

Later JAIN helped Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay organize the Indian Cooperative Union and applied its principles to the handicrafts industry. As secretary of the All-India Handicrafts Board, he fostered decentralized production and directed training, technical services, and loans to India’s struggling self-employed spinners, weavers, carpenters, and metalsmiths. JAIN set high standards and applied modern marketing techniques to promote handicrafts sales abroad and organized the Central Cottage Industries Emporium to expand the market at home. He championed artisans against mechanization and mass production and continues to do so. His efforts helped millions of independent craftsmen carry on traditional livelihoods in security and pride and assured the survival of precious arts and skills.

JAIN became a sage and independent-minded expert on development, applying unique organizational skills to wed theory to practice. In 1966 he led in establishing a chain of consumer cooperative stores where urbanites could buy food, clothing, and tools at a fair price. In 1968 he co-founded a service-oriented consulting firm. By seeking the advice of farmers and workers, JAIN and his like-minded colleagues helped government, industry, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) design modernization projects that are relevant and effective.

JAIN has found his niche as a bridge between peasants, artisans, women, and members of scorned castes, on the one hand, and development agencies as well as government committees and boards, on the other. His counsel is not always popular or heeded, yet it is sought by the powerful and powerless alike, for JAIN is a constructive critic whose love for India and its people is deep and clear.

Intellectually a cosmopolitan JAIN is at ease in international circles and among India’s most influential leaders. At home he prefers a life of simplicity, a life he shares with his wife, Devaki, and their two sons. A practical and modern man, JAIN nevertheless perseveres as a pragmatic visionary in advancing Mahatma Gandhi’s humane aspirations for India.

In electing LAKSHMI CHAND JAIN to receive the 1989 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Public Service, the Board of Trustees recognizes his informed and selfless commitment to attack India’s poverty at the grass-roots level.

Thirty-two years ago I came to this great country to study the Agricultural Credit Cooperatives and Farmers Associations Program, popularly called the ACCAFA Program. It was a most inspiring and instructive experience. The visionary Ramon Magsaysay, who had initiated ACCAFA, was still alive. I really received my first Magsaysay award in being able to study here at that time.

People like myself — engaged in the reconstruction of India, or in what Mahatma Gandhi called the tasks of the second revolution, the first being liberation from colonial domination — were thrilled with the creative potential of your experiment. Nowhere in the world had we come across such a well-conceived cooperative program, supported by the state through effective legislation and policies, which aimed to support the rural people in their endeavor to improve their lives.

Ten years earlier, on attainment of Indian independence, Prime Minister Nehru had awakened our interest in cooperatives, which he regarded as the embodiment of social and economic democracy and vital for reinforcing political democracy. Nehru also broadened our horizons beyond national boundaries. A vibrant Asia, asserting its personality and potential, was his dream. To achieve this dream he invited the leaders of Asia involved in the struggles for national independence to the Asian Relations Conference, held in New Delhi in 1947 — the first firm step toward Asian cooperation. Here, too, as I served on the secretariat of this conference, I received an enduring gift: the awareness of greater Asia.

In the fifties an award such as the Ramon Magsaysay Award was accepted casually. Those were times when all newly independent countries, and those recovering from the ravages of war, were full of verve and the confidence that they could banish poverty and inequality. But today’s ceremony is a grim reminder that in the past thirty years, poverty and disparities have continued to defy our prescriptions and methods. Today, when the promise of Gandhi’s second revolution remains still unfulfilled, which one of us can really feel comfortable with this public honor?

Where do we turn for light? In a village in Maharashtra a woman was elected as the president of the local village council?the panchayat, as it is called.

At a recent meeting she told our prime minister that when she assumed office there was no school in her village, no source of safe drinking water, no road to link the village with the outside world. However, she did not rush to the government to complain or plead for assistance. She gathered the village people and asked: “What good are we if we let the lives of our children be ruined without education as we have ruined our own?” The people, she said, were spurred to action.

“But,” asked the prime minister, “how could you mobilize the village community? Is it not divided by conflicts drawn from caste, class, and family feuds?”

“Yes, it is divided,” she replied. “We have all these troubles and more. But we talked and talked and talked. Then the people said, we have talked enough, let us do something.”

Responded the prime minister: “Surely that could not have ended your problems.”

“No,” the woman leader answered, “it did not.”

“So what did you do?” asked the prime minister. Said the panchayat woman: “Very simple, we talked more, we gathered again and again and talked more till agreement was reached and then the action was swift.”

The story of this woman leader is not an isolated one. In our state of Karnataka we have some fourteen thousand women elected to village panchayats out of a total of some fifty-six-thousand elected representatives who took office less than three years ago. They have lit up the countryside. They have brought about a dramatic change in the mobilization of local resources, in the purposeful and efficient use of these resources, and in the promotion of equity. And all these accomplishments have been far better and more satisfying to the village population than those achieved, in the preceding decades, through reliance on the bureaucracy to deliver development and social justice.

These grass-roots institutions and their leaders –not always women — have thus broken the Gordian knot of Third World development. The moral of the story is clear: while leaders have failed to dispel the darkness, millions who have a real stake in building a bright future have been able to light the lamp.