- For five years, he talked to more than a thousand victims and witnesses of human rights and environmental abuses connected to the building of the Yadana Gas Pipeline which was financed by the US-based Unocal and the French corporation Total

- In 1995, he co-founded EarthRights International, a non-profit organization with offices in the US and Thailand focusing on what it calls “earth rights,” the intersection of human rights and the environment, and combines “the power of law and the power of people” in defense of these rights.

- In 1996, EarthRights filed a case in the United States against Unocal with Unocal eventually compensating the eleven victim-petitioners in the case.

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes his dauntlessly pursuing nonviolent yet effective channels of redress, exposure, and education for the defense of human rights, the environment, and democracy in Burma.

In Burma, large-scale human rights abuses are being committed and natural resources despoiled by the ruling military regime. The voices of the victims have largely been silenced. One young man has decided that these voices should be heard in the outside world, and their legitimate concerns addressed.

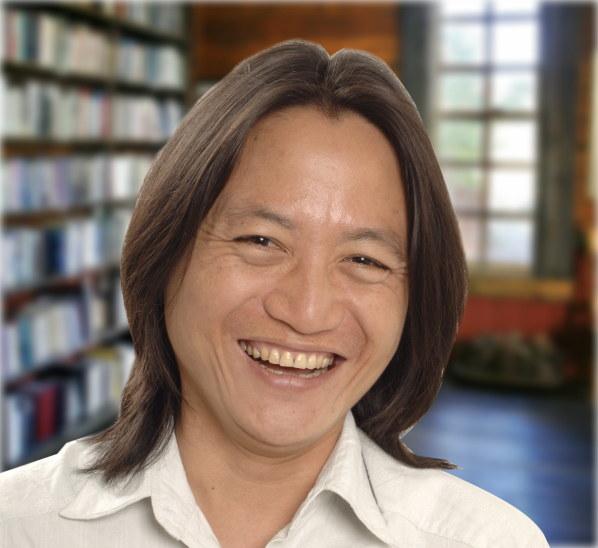

KA HSAW WA ceased to be a teenager abruptly and prematurely. As a seventeen year-old student activist in the anti-dictatorship demonstrations of 1988, he was arrested and tortured for three days by the military. Subsequently, in the aftermath of the student uprising of August 1988 when an estimated ten thousand people were killed, he fled to the jungle (as did many others) to seek refuge. His wanderings exposed him to scenes and stories of the horrible atrocities committed against ordinary villagers. He decided then, instead of taking up arms as an insurgent as he had planned, he would take up the pen, record the abuses, and find a way to get these stories out into the world.

For five years, he talked to more than a thousand victims and witnesses of human rights and environmental abuses. Most of these abuses were connected to the building of the Yadana Gas Pipeline. Financed by the US-based Unocal and the French corporation Total, Yadana was then the largest foreign investment in Burma. In enforcing the project, the ruling junta, the project’s principal beneficiary, had militarized the area along the pipeline, dislocated communities, imposed forced labor, and damaged a rich, biodiverse environment.

KA HSAW WA was later joined in his documentation work by a visiting law student, Katie Redford, who had entered Burma to investigate the human rights situation. In 1995, they founded EarthRights International; they were married the following year. EarthRights is a nonprofit organization with offices in the US and Thailand. It focuses on what it calls “earth rights,” the intersection of human rights and the environment, and combines “the power of law and the power of people” in defense of these rights.

In 1996, EarthRights filed a case in the United States against Unocal with the help of private and public-interest lawyers. The suit alleged that Unocal was complicit in the human rights and environmental abuses committed by the Burmese military in the building of the Yadana pipeline. After nearly ten years of complicated litigation, Unocal agreed to compensate the eleven victim-petitioners in the case. The petitioners decided to commit substantial funds from the compensation to humanitarian relief for other victims.

This precedent-setting case has served as a warning to the Burmese government and to multinationals investing in Burma. It has also inspired KA HSAW WA and EarthRights to investigate other infrastructure projects in Burma and the larger Mekong Region, such as the mega-dams along the Mekong River and the Shwe natural gas pipeline project in which Burma’s military junta is collaborating with foreign investors.

EarthRights does much more than litigation-related work. It carries out research, publication, and advocacy on behalf of the people of Burma. It maintains EarthRights Schools in Thailand, training young people from Burma and other countries in nonviolent social change, environmental monitoring, and community organizing. Its network of alumni has become, for EarthRights, an important resource for mutual assistance and information sharing. Equally important, the network has inspired EarthRights to hope that by training young people from Burma and neighboring countries it is planting the seeds of civil society throughout the region. Despite the constant threat of government reprisal, Ka Hsaw Wa stays committed to the mission he found in the jungles of Burma. “There’s no dead end for me,” he says. “I don’t give up easily, and I don’t like to give up.”

In electing KA HSAW WA to receive the 2009 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Emergent Leadership, the board of trustees recognizes his dauntlessly pursuing nonviolent yet effective channels of redress, exposure, and education for the defense of human rights, the environment, and democracy in Burma.

Thank you so much. I am so honored to receive for this Award, especially here in Asia, where many government officials — especially those in my country — like to say that human rights is a Western concept. They say that human rights is not part of Asian culture, and this award is an important testimony to what I believe: that human rights are universal and all of us are entitled to dignity and human rights.

I believe that one of the most fundamental human rights is the right to a clean and healthy environment. If you look around the world you can see so many human rights violations go hand in hand with the exploitation of natural resources, and the destruction of the environment. This is the main focus of EarthRights International, where we combine the power of law and the power of people in defense of human rights and the environment.

In Burma, when corporations mine for gold, jade, copper and other precious resources, they do not let local people or sensitive ecosystems get in the way of their quest for the highest profit. In the process, they use chemicals and procedures that are outlawed in other parts of the world, whether or not these poison the villagers, the wildlife, or the ecosystems. Many people are suffering new diseases, dying in new ways due to pollution caused by the mining industry in my country. Is this a human rights or an environmental problem? Usually, pollution is considered an environmental problem. But I believe that this is an earth rights issue-the violation of both human rights and the environment.

Think about this: when Unocal hired the brutal Burmese military to secure its gas pipeline, soldiers forced people off their lands, forced them to work as slaves, raped women and girls, and tortured and killed those who got in their way. These were earth rights abuses. When people could no longer feed their families because their farms had been destroyed, their forests logged, and they had to flee their homes to become refugees, these were earth rights abuses. We knew this was injustice, and we had to do something to demand for accountability. But how do you do that in a country like Burma, ruled by a brutal military dictatorship? And as if that is not difficult enough, how do you do that when that junta is supported by powerful U.S. oil companies?

What we did, and what we still do, is simple. We give tools to people to help themselves. In the case of Unocal, we used the law-we trained villagers and community leaders from Burma on how to document human rights abuses, then took that documentation and filed a lawsuit in U.S. courts. Using international human rights law, we demanded justice for the rape, torture, killing, forced labor, and other abuses that Unocal helped commit while building their Yadana gas pipeline. The world thought we were crazy-people laughed at us-how can the world’s poorest, most oppressed people take on a powerful junta and powerful oil companies? With the law as our weapon and hope as our strength, in 2005 we took one big step on the long road to justice when Unocal paid compensation to the villagers who sued them. These villagers sent a message loud and clear to human rights abusers everywhere: no matter where you are-in Burma, or anywhere else in the world-you can’t escape responsibility when you violate the earth and its people.

This is still our simple strategy. We train and work with emergent leaders from communities who are on the front lines of destructive projects like gas pipelines, mines, dams, what our governments like to call “development” projects. We have two EarthRights Schools that train people like me-from countries like Burma, China, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam and Thailand who want to stand up to injustice and make a difference for their communities. And we use the law as one important tool to help people find nonviolent solutions to some very violent and destructive realities.

In all Asian countries, people need a healthy environment to live. And people need human rights-like freedom of speech and association, and access to information-to protect their environments. You cannot separate human rights from the environment. You cannot separate corporate abuse from government abuse. And most importantly, we cannot be divided or separated from each other. All of us must stand together to protect this one planet that we have, that we all depend on, for our own dignity and the future of our survival.

There are many people like me who work every day, in secret, in hiding, and at great risk to themselves to protect their people and their planet. This award is for all those people who choose to address human rights and environmental abuses and who keep their commitment to justice in their hearts. I thank and honor all who speak the truth to those in power, and do so with dignity and graciousness. And I thank all of you who have made this evening happen.