- LAXMAN’s genial wit reached its apotheosis in the daily cartoon, You Said It, begun in 1957 and featuring the bewildered and dearly beloved character, the Common Man

- His trademark is his portrait of the Common Man — a small figure with a bulbous nose, caterpillar eyebrows, the hair behind the ears bushing out below a bald pate, and mustache like a brush.

- LAXMAN, from the very beginning of his career, has been given free rein with his political cartoons, and he has never been sued for libel, perhaps because he never attacks public figures personally, nor draws them in a gross or vulgar manner.

- He only attacks their policies and punctures their complacency and inconsistencies. In consequence he is not bound by the editorial policy of the paper, and is permitted to send his cartoons directly to the printer.

- The RMAF Board of Trustees recognizes his incisive, witty, never malicious cartoons illuminating India’s political and social issues.

Cartoonists are a special breed within the journalistic fraternity, and around the world first-rate practitioners are very rare. Because they can pierce the heart of a problem with the few lines of a sketch, they are understood as well by the less literate as by the erudite. The feelings a powerful cartoon evokes involve the total personality, rather than only literate faculties.

With this unique effectiveness a gifted cartoonist can blacken the prospects of a public personality with a single sketch of his chin or nose. But this talent must be tempered by a sense of the broad underlying yearnings of the society, plus a persistent search for the truth that lies beneath surface appearances. No school has yet been able to produce gifted cartoonists; they are born and self-trained.

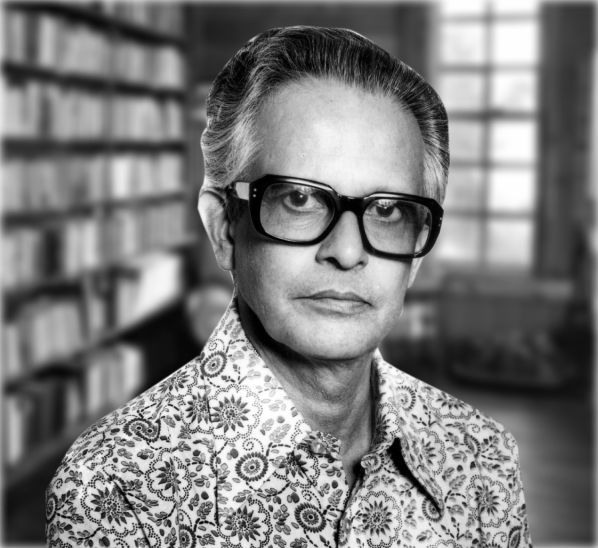

From an illustrious intellectual family in Mysore, South India, RASIPURAM KRISHNASWAMI LAXMAN was drawing by the time he started school. Self-taught, in high school he was illustrating the short stories of his author-brother, R.K. Narayan. He also began to study the cartoons in The Hindu by David Low, dean of British cartoonists, who would one day visit the young man in Bombay and compliment him on his work.

When LAXMAN started to work on the Free Press Journal in Bombay in 1946, Indian newspapers had yet to appreciate the power of the political cartoon. It was after he joined The Times of India in 1947 that LAXMAN’s extraordinary talents were recognized. Today many readers look first for his cartoons when they pick up their morning papers. Meanwhile he has expanded his talents to become an accomplished writer of short stories, articles, travelogues and a novel, Sorry, No Room.

Besides his newspaper readership LAXMAN has reached out to another audience for his cartoons. For nearly 30 years his cartoons You Said It have appeared in inexpensive paperback books. The preface to an early volume, reprinted in six editions, gives the flavor of his occupation:

“A cartoonist works for an industry in which time is of the essence. The Damocles sword of deadline rules his days, which for him follow one another in a bewildering order of importance: tomato shortage, nuclear threat, five-year plan, pot holes, corruption, monsoon forecast, adulterated drugs, prohibition and mission to the moon…”

LAXMAN?s trademark is his portrait of the Common Man — a small figure with a bulbous nose, caterpillar eyebrows, the hair behind the ears bushing out below a bald pate, and mustache like a brush. His dress is unchanging — a dhoti, long shirt and checked coat. His mien suggests a determined staying power. As his creator wrote: “You can not do away with the Common Man. They have tried it for centuries and not succeeded. . . he is the mirror image [of millions of readers] . . . the conscience that pricks the evildoer, the social offender, the practitioner of all those trades which we might have liked to practice but for fear of the police, if not of God.?”

Through the eyes and fate of this long-suffering, harried, cheated and burdened, yet brave and uncomplaining character, LAXMAN gives his readers a sense of identity with the experiences that constitute India’s national life. Both the bad and the good become real and shared.

This ability of now 60 year old LAXMAN, the cartoonist, has prompted journalist colleagues to dub him their “national treasure.” For above all it is through public enlightenment that civilizations stumble up the long stairway that supposedly leads to progress. And as India wrestles with the compounding dilemmas of the world’s most populous democracy, it is the sane and hopeful daily effort of persons of LAXMAN’s profession of journalism that must help point out the better paths.

In electing RASIPURAM KRISHNASWAMI LAXMAN to receive the 1984 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Journalism, Literature and Creative Communication Arts, the Board of Trustees recognizes his incisive, witty, never malicious cartoons illuminating India’s political and social issues.

I am overwhelmed by your kind decision to select me to receive the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award for Journalism, Literature and Creative Communication Arts.

I did not imagine for a moment that my efforts in this field merited a reward of such dimensions. I thought all along I was providing a momentary relief to a public leading a monotonous humdrum existence. I pondered over this happy news and I realized the significance of the Award in relation to my role in society, and at the same time arrived at a very revealing philosophy. At the risk of it being considered somewhat too fanciful I would like to share it with you.

In this world there is no man who can say he is free from problems and nagging worries. A rich man has his worries about his wealth, I am sure, and so a poor man, obviously, has his about his impoverished state. The masses of people in between are, one way or another, victims of varying degrees of frustration, stress and tension. With these rather liberal assumptions and a dash of creative imagination, one can picture the common man running away in horror from the specter of poverty and at the same time, alas, not quite making it to the haven of contentment. In such a situation he bemoans his lot and blames it on rulers, administrators, petty officials, tax collectors, taxi drivers, grocers, doctors, judges and a score of others he has to deal with.

At this pyschological juncture the satirical commentator, in this case the cartoonist, steps in to administer the anodyne to his frustrated spirit and tickles his almost atrophied sense of humor.

I draw cartoons satirizing and lampooning his tormentors. He takes a look at them. A slow smile spreads over his face as he views his persecutors ridiculed and derives a vicarious comfort, as if he has been avenged! Such a pictorial comment helps him, to some degree, overcome his blues and relax his overwrought mind. Thus prepared he goes to face the battle of life, not with an impotent anger in his heart, but with a healthy good humor and an affable disposition, and survives another day.

A sense of humor is very essential for human welfare. A man with this quality is a better neighbor, a better friend, and above all a better citizen than the grumpy one among us who is bereft of it. Laughter is Mother Nature’s device to insulate us against the onslaughts of harsh realities of existence. God must have, in his infinite wisdom, realized the sad state of the human condition on earth very clearly indeed.

That is why, I suspect, that of all the animals he created, he gave the gift of laughter only to humans so as to help them survive. It is the business of the satirical commentator to kindle, stimulate and develop this instinct in man for the collective good of the whole civilized community. I like to believe that this Award is a tribute to that supreme quality of laughter which we all possess. I am grateful to the enlightened trustees of the Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation for recognizing with such a grand and noble gesture the importance of this human quality and the significant role that it plays in our lives.