- In 1943 he inspired the organization of an association of young artists known, as the “43 group†that has now become one of Asia’s more important art schools.

- In a course of three decades, he has published 155 serious articles in Sinhala and 55 in English, bringing to public ken the ancient and medieval art of Sri Lanka.

- Visiting hundreds of viharas, or temples, sometimes living on wild fruits from the jungle, he systematically documented, and copied or traced, thousands of neglected and fast disappearing mural paintings.

- The RMAF Board of Trustees recognizes his preserving for the people of Sri Lanka and the world the 2,000-year-old tradition of classical art found in their great Buddhist temples.

Neglect, decay and sometimes desecration of cultural monuments to Asia’s past are among the major tragedies of this age. For all of their feudal ways, rulers of antiquity did truly patronize the arts. Religious architecture, sculpture, painting and monumental constructions often were created in part with carves labor. Taxes that supported the artisans frequently were onerous for the peasants. However, religious faith, combined with leaders’ desire of leaving an enduring heritage, inspired the finest artistic expressions of these ancient civilizations.

Secular societies now seem especially prone to forget their origins, and mass communications cater to the least common denominator of taste. Artists are left seeking a constituency among the small minority who take time to cultivate appreciation. Often today they are helpless to prevent the plastering of old church frescoes and weathered temple paintings in the name of modernization.

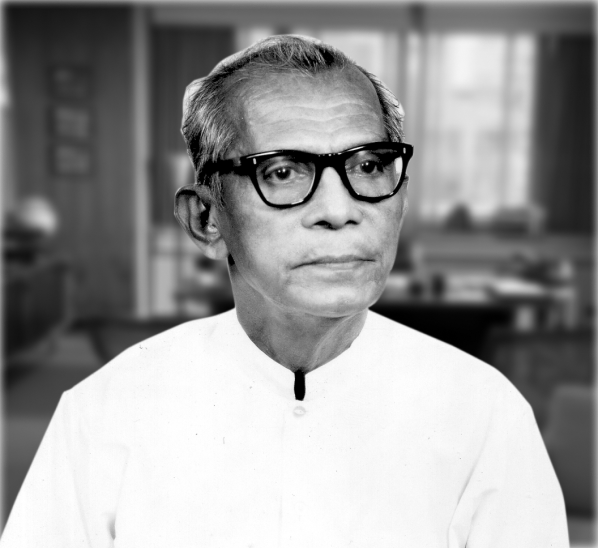

Born 77 years ago to poor parents in the fishing village of Alutgama in then Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, MANJUSRI had to borrow a shirt to attend school. After apprenticing as a carpenter, he joined the Buddhist sangha (monkhood) as a novice at the age of 13. He was fortunate in studying under two famous teachers at the Mangala Pirivena in Beruwala, learning Buddhist philosophy and four languages: Sinhala, Pali, Sanskrit and Bengali.

MANJUSRI’s artistic sense was awakened in 1932 when he went to study at Santiniketan Ashram of Rabindranath Tagore in eastern India. He was inspired after two years to return to begin copying the old temple paintings in Sri Lanka, which work, by 1936, had won the admiration of the scholars at Santiniketan. After further study of the Lamaist sect of Buddhism and Buddhist artistic traditions in Sikkim and the Himalayan heights, the gifted monk turned his talents to his life work.

In 1943 he inspired the organization of an association of young artists known, as the “43 group†that has now become one of Asia’s more important art schools. After his own original paintings were exhibited in Colombo, together with his reproductions of temple art, MANJUSRI was invited to London and Vienna where this wealth of the Buddhist artistic tradition began to be appreciated.

Taking off the robes of a Buddhist monk, MANJUSRI in 1950 turned his full attention to art and writing. Over the past 29 years he has published 155 serious articles in Sinhala and 55 in English, bringing to public ken the ancient and medieval art of Sri Lanka. Visiting hundreds of viharas, or temples, sometimes living on wild fruits from the jungle, he systematically documented, and copied or traced, thousands of neglected and fast disappearing mural paintings. In between he translated world classics including poems by Tagore into Sinhala.

Marrying late in life, MANJUSRI now is assisted by a devoted wife, Mangala, an artistic son and two daughters. They and the Archaeological Society of Sri Lanka helped him prepare for publication on his 75th birthday his book, Design Elements from Sri Lankan Temple Paintings, complete with 159 plates of designs from 75 temples. In their modest flat he and his family have created a haven where other artists now gather to cooperate in preserving Sri Lanka’s rich artistic tradition.

In electing LOKUKAMKANAMGE THOMAS PEIRIS MANJUSRI to receive the 1979 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Journalism, Literature and Creative Communication Arts, the Board of Trustees recognizes his preserving for the people of Sri Lanka and the world the 2,000-year-old tradition of classical art found in their great Buddhist temples.

The Ramon Magsaysay Award is well known in my country because three of my compatriots have received it before me. They were distinguished and well-known people. I am a poor artist, a painter. I never thought that I, too, would receive it one day. I thank the Board of the Ramon Magsaysay Foundation and the Executive Trustee for this great honor conferred on me, and thereby on my country.

I am a painter by accident. A long time ago, when I was a Buddhist monk, I spent a few years at the poet Tagore’s ashram, Santiniketan, in Bengal, India. During this time I used to see young people sketching and painting in the art school. My curiosity was aroused, and I began to paint too, by myself. This was in 1932.

By the time I returned to Sri Lanka in 1934 my experience at Santiniketan had awakened me to the beauty of art. I began to look at the paintings on our temple walls with new eyes. I saw that valuable temple murals were neglected, destroyed and replaced by cheap, meaningless, tasteless modern paintings. I decided to copy what was left, before they too were destroyed.

The Buddhist clergy and some groups of painters were opposed to what I was doing. They said that engaging in activities like painting was unethical for monks. Instead of being helped and encouraged, I was obstructed and discouraged. But I continued, with the determination that I had to save these treasures for posterity. I copied them faithfully, traveling the length and breadth of the land to find them on crumbling temple walls. I wrote to the newspapers about them, illustrating what I wrote with the sketches I had made. I wanted to awaken my countrymen to the need to preserve this cultural heritage for future generations.

Gradually, monks as well as laymen began to realize the value of this art of their forefathers. People began to collect my newspaper articles in Sinhala and in English. Some collected them in files; others bound them in book form.

There are still more temples to visit; more murals to copy; and many more to protect and preserve. But I can no longer undertake this task unaided. Perhaps with this Award I may find some help.