The state of war in Afghanistan over the past decades has exacted a toll not too widely recognized. In the midst of the country’s civil strife, the bombings, looting, and willful destruction by the Taliban of what they considered “non-Muslim†heritage have resulted in the massive loss of priceless historical and cultural treasures. Called the “crossroads of civilizations,†Afghanistan is a country rich in an ancient, cosmopolitan heritage of Hellenistic, Hindu, Buddhist, and Islamic cultures. The loss of this heritage is of profound importance to Afghanistan and to the world.

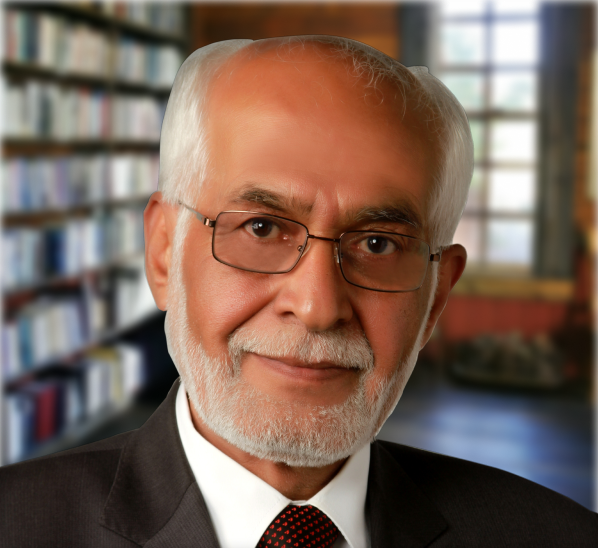

One man has been engaged, against great odds, in preserving the Afghan heritage for generations present and future. Trained in history, sixty-six-year-old OMARA KHAN MASOUDI joined the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul in 1978 and became its deputy director in 1998. He witnessed the ferocious assault on his country’s cultural patrimony. The museum was bombed and looted. Under a Taliban decree that authorized the destruction of objects considered un-Islamic, the famous, sixth-century Buddha statues of Bamyan were rocket-blasted and reduced to rubble, and hammer-wielding Taliban entered the museum and smashed works of art they deemed “idolatrous.†In 1979, the museum had some one hundred thousand objects; by the mid-1990s, 70 percent of these treasures had been destroyed, looted, or lost.

At great risk to his life, MASOUDI led his colleagues in moving some of the most precious objects—including the world-famous Bactrian treasure of some twenty thousand ancient gold ornaments—to the safety of other locations, and secret vaults deep underneath Kabul’s city streets. Their locations were known only to MASOUDI and a few other colleagues, who swore never to reveal to the Taliban the secret. Forced out of the museum by the collapse of government, MASOUDI stayed on in Kabul and supported his family by selling onions and potatoes on the sidewalk, while keeping an eye on the museum.

It was only when the Taliban rule ended in 2002 that he could return to the museum. Appointed museum director under the Karzai government, MASOUDI faced the herculean task of rebuilding a damaged and depleted museum. Despite the extremely difficult circumstances, he succeeded: resurrecting the collections he and his colleagues had hidden and saved, restoring historical monuments, and repairing broken museum objects. He also successfully negotiated the return of Afghan cultural treasures that had been moved or smuggled to foreign countries, and organized expositions in foreign countries to raise funds and promote international appreciation and support for Afghan cultural preservation. For more than a decade, MASOUDI has supervised the physical rehabilitation of the museum, and initiated training programs to build a pool of museological expertise. He even upgraded and expanded the country’s network of provincial and satellite museums.

The museum in Kabul was reopened to the public in 2004; its depleted collections have been built up to sixty-five thousand items and up to twenty-five thousand visitors now come to the museum yearly. Much work still needs to be done and the political situation in Afghanistan remains fragile, but the National Museum has been amazingly resurrected from the ashes.

In front of the museum in Kabul these words are encrypted in stone: “A nation stays alive only when it can keep its history and culture alive.†These are words MASOUDI takes to heart. The museum, he says, is a ‘storyteller of the past,’ and it tells the story of how, for thousands of years, Afghanistan was enriched by the confluence of civilizations, and how Afghans have used these influences in positive ways, producing high forms of spirituality and great art. Torn apart by rabid intolerance in recent times, Afghans need to listen to this great story. MASOUDI says, “I’m hopeful that our culture can play a big role in creating space, in restoring national unity.â€

In electing OMARA KHAN MASOUDI to receive the 2014 Ramon Magsaysay Award, the board of trustees recognizes his courage, labor, and leadership in protecting Afghan cultural heritage, rebuilding an institution vital for Afghanistan’s future, and reminding his countrymen and peoples everywhere that in recognizing humanity’s shared patrimony, we can be inspired to stand together in peace.

I am very happy to be here with you today to receive the Ramon Magsaysay Award from the foundation. I feel honored, humbled, and deeply moved by the decision to give me that important distinction.

I feel that I alone do not deserve this. Rather, it is my work and the work of my colleagues that has earned this honor. And, therefore, I accept it with profound gratitude on behalf of my staff at the National Museum.

I think that culture is an essential component of human development. It represents a source of identity, innovation and creativity for individuals and amongst communities. Thus, culture must become an integral part of development strategies and policies and should involve all development partners and stakeholders.

Safeguarding all aspects of cultural property in my country—including museums, monuments, archaeological sites, music, the arts, and traditional crafts—is of particular significance in terms of strengthening cultural identity. And it is preserving a sense of national integrity. Cultural heritage is a point of mutual interest, enabling us to rebuild ties, to engage in dialogue, and to work together in shaping a common future.

We—I and my team at the National Museum of Afghanistan—have helped protect the extraordinary collection of the Museum over many years. We are also making efforts to safeguard this Afghan history for future generations. Our strategy is to re-establish links between Afghans and their cultural history, helping to develop a sense of common ownership, while at the same time representing the cultural heritage of our diverse society. Our overall objective is to raise public awareness throughout Afghanistan about the value of its cultural history, and about the responsibilities for protection and preservation that the next generation will inherit.

International relationships are crucial to the future of the National Museum. The future lies in working together.