- Through panchayat raj, or village-based sovereignty, he aims to restore to the rural mass of Indians meaningful control over decisions most intimately affecting their daily lives.

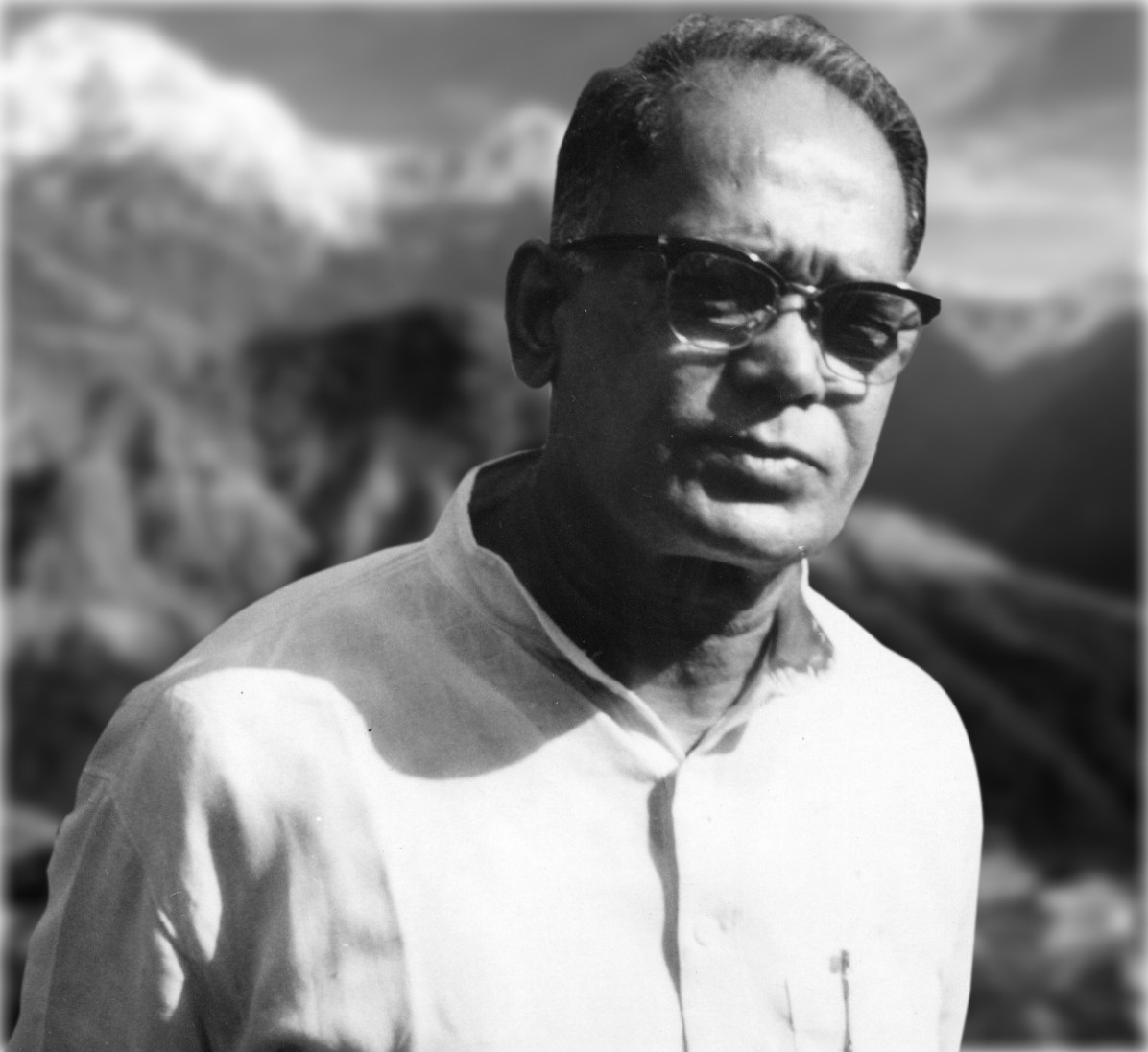

- Following in the path of his great mentor, Mohandas K. Gandhi, NARAYAN also has given new relevance to “non-violence†as a concept for resolving conflict and protecting the rights of minorities.

- The RMAF Board of Trustees recognizes “his constructive articulation of a public conscience for modern India.â€

Like our own José Rizal, JAYAPRAKASH NARAYAN has had the courage to see and say that forms such as independence, nationalism or socialism in themselves offer no adequate answers to man’s most basic needs. When, through bureaucracy, over-centralization, distortion of purpose or otherwise, they make tyranny a handmaiden, their worth is discounted.

Instead, NARAYAN begins with the individual, his yearning for liberty and his need to become equal to its demands. Through panchayat raj, or village-based sovereignty, he aims to restore to the rural mass of Indians meaningful control over decisions most intimately affecting their daily lives. The Sarvodaya, or Force of Service, Movement is his instrument. As its President, he has mobilized some 10,000 volunteers to carry this revolution in ideas to the countryside where they energize, and integrate with, efforts at bhoodan, or “land gift,†and local self-government.

Following in the path of his great mentor, Mohandas K. Gandhi, NARAYAN also has given new relevance to “non-violence†as a concept for resolving conflict and protecting the rights of minorities. In the bitter feud between Pakistan and India over Kashmir, he was the architect of an entente that opened the way for greater sanity. Rebel Nagas and ruling Indian authorities acceded to his persuasion in agreeing to negotiate the issue of Naga demands for a separate state. Tibetans resisting the imposition of Chinese Communist imperialism found in NARAYAN a champion who alerted his countrymen.

The route by which NARAYAN arrived at his present views and stature largely parallels India’s history over the half-century since his birth in a tiny village in the state of Bihar. Returning from study in the United States as a radical revolutionary and Marxist, he was repeatedly imprisoned and several times escaped arrest during the struggle for independence. Although the organizer of the Socialist Party and apparent heir to major leadership in his new nation, he renounced dialectal materialism and power politics a decade ago to devote himself to the more lonely and unrewarding task of enlightening and guiding his countrymen on crucial problems many were reluctant to face.

By personal modesty wedded to clarity of thought and force of personality, NARAYAN has shown that the moral strength of truth can make a difference. Some Indians regret his refusal to become involved in the complexities of administering government, but few can doubt his contribution in dispelling the myths of formulas that offer trite solutions. Through NARAYAN, India’s heritage of accumulated insights and methods for translating human values into action is being given contemporary relevance at home and abroad.

In electing JAYAPRAKASH NARAYAN to receive the 1965 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Public Service, the Board of Trustees recognizes his constructive articulation of a public conscience for modern India.

I feel greatly honored to be here today, a great day for the people of the Philippines, a day of remembrance and dedication—remembrance of a great leader of men and dedication to his great ideals of freedom and fulfillment of the human spirit. This Award and this day make it possible for peoples beyond these islands, which Ramon Magsaysay was privileged to serve and lead, to participate in this inspiring ceremony of remembrance and dedication.

I should like to express my gratitude to the Trustees of the Magsaysay Award Foundation that they found me deserving of this honor, and for their generous citation. In this I find not a personal recognition but recognition of the ideas that I have been pursuing and trying to translate into action. In that sense this Award will be a source of much encouragement to me and my colleagues in the work that we are doing to build a new India.

As an Indian I feel proud that since their inception, one of these Awards has gone every year, except for one, to my country. This indeed is an indication of the high regard in which the people of these islands hold India. Let me on my part assure you that the people of India reciprocate in full measure this feeling of friendship and hold you in great affection and regard. I hope these Awards will be a powerful bond to bring our countries closer than they happen to be today.

All the countries of the world—of Asia, Africa and South America—that have won their freedom in recent times and whose natural growth had been retarded on account of the bonds of colonialism, are trying to catch up with the advanced countries and build their societies as fast as possible. In this the model many have before them is that of the highly industrialized and affluent West. A few countries have set up before them the Eastern model presented by successful communism, whether Russian or Chinese. There is much in both the Western and Eastern models that is of abiding value and that the developing countries should accept and assimilate. The ideals of individual liberty, of government by consent and of the rule of law that the Western model has, by and large, emphasized as the true foundations of society’s political organization, are undoubtedly ideals that should be adopted and assimilated by the developing peoples. In the same manner, the concern of communism for the toiler and its drive toward greater economic equality are values that must also inspire and guide them.

But there are.in both models essential characteristics that, to my mind, should be rejected. In the Western model, the ruling ethic is that of individualism and competition, it being assumed that in the process the weaker will be driven to the wall. There is also an excessive emphasis on the satisfaction of material needs and their consequent multiplication, leading to serious imbalances. Western life is also unbalanced for the reason that sufficient attention is not paid, on account of the predominance of certain utilitarian and commercial values, to the interrelationship between man’s work, leisure, habitat and happiness. The drive towards urbanization, resulting in the monster of the megalopolis, has destroyed the community, divorced the urban from the rural and forcibly alienated man from nature. The result is a distorted growth of man and society.

On the other hand, the communist model also presents a distorted picture of human and social development. It strikes at the very root of man, by denying the primacy of his spirit and by deliberately suppressing it. By glorifying power and authority, as represented by the party and the state, and by making everyone and every thing subservient to them, it makes of society a vast prison house for the human spirit.

The new countries, therefore, while rejecting in totality both these models, must take from them what is of value and conducive to balanced spiritual and material growth of man and society. Happily, in the advanced countries themselves, particularly of the West, much thought is being given to this problem, and there is also some experimentation. These should be of great value to the new countries.

Development of science, both physical and social, has made it possible for the first time in history for human societies consciously to shape their future. But in no society, not even those where the sciences have developed farthest, are men prepared to be guided by science. They have their narrow interests, their prejudices and predilections, their concern with immediate things, their myths and ideologies—all these make the voice of science a cry in the wilderness.

As far as the new countries are concerned, even though they have an almost clean slate to write upon and a wonderful opportunity to select the best from the extant models and reject the rest, two circumstances make it almost impossible for them to do so.

Firstly, vast numbers of the peoples of these countries are too uneducated to be able to draw upon the teachings and techniques of science; and secondly, they are economically so backward and poor that their single overpowering anxiety is to secure before all else their economic development. This is understandable. But there was no reason to believe that economic development would have suffered if equal attention had been paid to the task of achieving a balanced human and social development. Indeed, if economic development had been thought of in terms of economic well-being of the mass of the people and not in terms of providing a base for industrial and military power, there should have been every reason to believe that the rate of development might have been faster.

Many of the new countries, it hardly needs to be pointed out, present such unstable societies—due either to their having become arenas of the power-struggle that rages between the mighty nations or to their internal situation—that they will be unable for a long time consciously to build their future.

Nonetheless, it needs to be stressed that even those new countries that are in some position consciously to direct their future course, have no clear picture of their goals apart from such cliches as democracy, socialism, communalism, industrialism, modernism and the like.

The central point to be stressed in this connection, and with that I wish to conclude, is that the question posed here is a question of values. Looked at from that standpoint it should not be difficult, not only to chalk out the course for the future, but also to achieve a consensus of public opinion behind the endeavor to reconstruct a new society.