- While living in Tokuyama City he discovered that a wealthy man had opened his library to neighbors, and OHM was amazed at the knowledge stored in books. As he read avidly, OHM vowed that when he had made enough money he would bring back books to villagers in Korea.

- In 1951, in his hometown of Ulsan in southern Korea, OHM used his private collection of some 3,000 volumes to found a library open to the public.

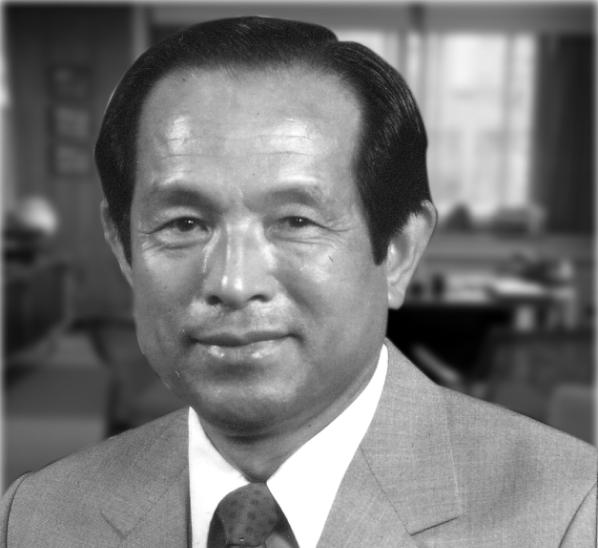

- For professional librarians OHM helped organize and fund the Korean Library Association. At the age of 59 his driving motivation remains the concept that “only knowledge can make man free.”

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes his abiding commitment toward making knowledge a tool for life-betterment in rural Korea.

The rebirth of their ancient civilization in South Korea during the past 15 years is among the major historical events of modern Asia. Korean culture, dating back more than 3,000 years, stagnated during the 18th and 19th centuries as the “hermit kingdom” isolated itself from the outside world. When Japan in 1910 formally incorporated Korea into its empire, indigenous history, literature and learning were suppressed.

With all formal education available only in Japanese, Koreans seeking to preserve their heritage returned to the study of the archaic stylized literary forms of the yangban, the scholar-gentry officials. Ordinary rural folk, however, were not in the position to learn the complex pictographic language that would enable them to read the Confucian classics. When Korea was liberated by Japan’s surrender to the Allies in August 1945, all this changed. Korean became the language of literature, government, commerce and education in a public school system aimed at universal literacy. Perhaps inevitably the emphasis was urban; even today there are only 118 public libraries in the country, rarely within reach of rural families.

The Village Mini-Library Movement originated from a fortuitous happening in OHM DAE-SUP’s childhood after he moved with his poor family from Korea to the Kobe area of Japan. While living in Tokuyama City he discovered that a wealthy man had opened his library to neighbors, and OHM was amazed at the knowledge stored in books. As he read avidly, OHM vowed that when he had made enough money he would bring back books to villagers in Korea.

In 1951, in his hometown of Ulsan in southern Korea, OHM used his private collection of some 3,000 volumes to found a library open to the public. By bicycle he distributed metal bookcases to 50 villages, organizing a free circulating library. After two years he moved his library to Kyongju, and discovering that it was not enough merely to distribute books, he organized community reading clubs to overcome the villagers’ apathy to reading. He also fostered local leadership in selecting, sharing and caring for books, and in discussing their contents.

A decade later the Maul Munko (Village Mini-Library) association was formally inaugurated. Despite scoffers, OHM continued selling his assets to pay the costs of the Mini-Library Association. He lives now on income from a small building and a lot his two younger brothers bought for him in Pusan in their names so that he could not sell them for more books. Meanwhile, OHM’s struggling private, non-profit group learned to select and purchase wholesale from publishers books which deal primarily with farming, fishing, children’s and women’s interests, literature and hobbies. Others banded with him to donate mini-libraries to their hometowns, and in 1965 the Ministry of Education began to pay for bookshelves and books. In 18 years OHM’s perseverance has resulted in mini-libraries in 34,389, or 95 percent, of South Korea’s villages. A Mini-Library Club of 10 to 20 mostly young village volunteers manages each collection.

The mini-libraries have now been incorporated in the Saemaul Undong (New Village Movement) which is upgrading and adding to the collections while OHM works unceasingly to bring all libraries up the standard of the one-third that are working well. Already this source of technical and cultural enrichment has contributed to the extraordinary economic and physical transformation of South Korea’s countryside. For professional librarians OHM helped organize and fund the Korean Library Association. At the age of 59 his driving motivation remains the concept that “only knowledge can make man free.”

In electing OHM DAE-SUP to receive the 1980 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Public Service, the Board of Trustees recognizes his abiding commitment toward making knowledge a tool for life-betterment in rural Korea.

Upon receiving the 1980 Ramon Magsaysay Award, I would like to begin by expressing my wholehearted appreciation for this most honored Award; and on this 73rd birthday anniversary of the late Philippine President, I wish to pay my highest respects to the memory of him who was the guardian of freedom and justice for this and other parts of the world.

My modest campaign for the nationwide reading movement for Korean farmers and fishermen, which the Magsaysay Award recognizes, dates back about 30 years. At that time Korean farmers and fishermen had little opportunity to read books. The few public libraries which were available were in cities. Books were the exclusive possession of the privileged elite of the society.

The people, especially farmers and fishermen, had to rely completely on their traditional way of thinking and life. My purpose in establishing village mini-libraries was to enable them to learn for themselves through books and to improve their way of thinking and life through the knowledge thus acquired.

My idea in establishing the mini-libraries was to provide small but easy-of-access reading facilities for farmers and fishermen. After I started this movement it grew rapidly with support from various segments of society. The movement now has the strong support of the Korean Government.

Today mini-libraries have been established in over 34,000 villages, which represent 95 percent of all the villages of Korea. Villagers themselves now operate established libraries without outside help.

As a result of their consciousness of their need for knowledge and information from books in this rapidly changing social situation, villagers have begun to acquire books by themselves. Although the number of books each mini-library has collected on its own is small so far, the people’s understanding of the value of books has grown substantially.

I firmly believe that for those whose formal education is limited, as is the case with farmers and fishermen, the most effective and permanent method of self-education is voluntarily to read books. In most developing countries, however, government investment in public libraries is grossly inadequate. As a result, the general public is in a pitiful situation with no systematic channel for obtaining books to meet their desire to read.

In modern society everybody has a right to read and acquire knowledge. This is an inherent right of a human being in this age. I also firmly believe that only knowledge can liberate human beings. Recognition of my work by the Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation convinces me once again that book reading is the prerequisite for progress of any developing country.