- With the Allied liberation early in 1945, he was appointed to reopen the municipality’s schools. Gathering all “degreed” people—doctors, lawyers, engineers, pharmacists and the like—he started a high school in a bombed out church.

- This first public high school outside of a provincial capital began with 350 students and grew to an enrollment of 1,700, with an additional 1,600 attending 15 branches in the barrios.

- Retiring again at age 65, he devoted his energies without remuneration to organizing barrio high schools and community colleges. With support from the Department of Education and enthusiastic participation by local citizens thus barrio high school movement has spread to 43 provinces and six cities.

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes his 44 years of creative work in education, particularly his conception and promotion of barrio high schools for rural Filipino youth.

Only in the 20th century have the great majority of parents around the world come to expect education as a birthright of their children. This near-universal hunger for schooling imposes demands on every government, prompting expectations that are at the root of much popular insistence upon change.

Historical circumstance and the zeal of early American and Filipino teachers gave the Philippines the first major public school system in South and Southeast Asia. With all its imperfections, our democracy is rooted in this educational system. Yet, it remains inadequate for today’s needs in both educational content and opportunities for schooling for three-fourths of our people who live in rural areas.

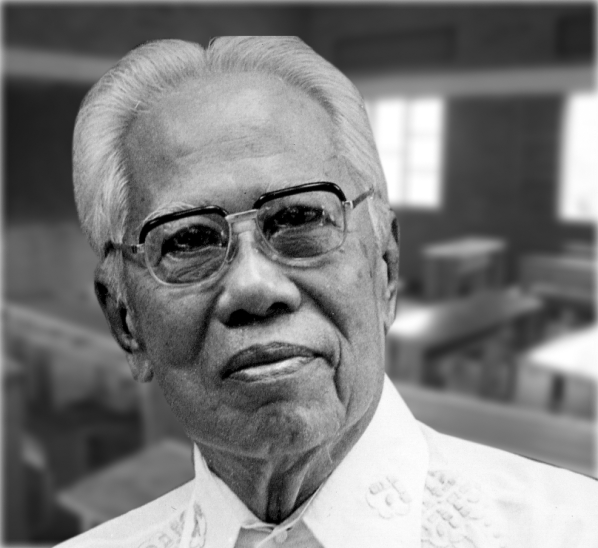

Since he first walked barefooted over the rice paddies as a poor farmer’s son to attend the barrio elementary school in Pangasinan where he was born in 1899, PEDRO ORATA has pursued his interest in education. Upon graduation in 1920 as valedictorian of his high school class in Lingayen, a sister’s savings allowed him to travel to the United States. Working on a railroad gang, washing dishes, and finally with partial pensionado support from the Philippine Government, he earned his Ph.D. in 1927 and came home to join the Bureau of Public Schools.

After teaching at the Bayambang Normal School and Philippine Normal College and serving in the Division of Research and Measurements, ORATA became successively Division Superintendent of Schools in Isabela and Sorsogon Provinces. Returning to the United States in 1934 as a professor at his alma mater, Ohio State University, he went on to develop an experimental community school on an Indian reservation in South Dakota. Coming home in 1941 he joined the Philippine National Council of Education.

ORATA’s experience matured into a personal philosophy of education during his enforced idleness in World War II. Caught in Manila by the Japanese occupation, he went back to Urdaneta, Pangasinan. With the Allied liberation early in 1945, he was appointed to reopen the municipality’s schools. Gathering all “degreed” people—doctors, lawyers, engineers, pharmacists and the like—he started a high school in a bombed out church. This first public high school outside of a provincial capital began with 350 students and grew to an enrollment of 1,700, with an additional 1,600 attending 15 branches in the barrios.

After devoting three years to helping reorganize the war-shattered Philippine school system, ORATA served abroad for 12 years with UNESCO. Upon retiring from this post, he became Dean of the Graduate School and then Director of Curriculum Development at Philippine Normal College. Retiring again at age 65, he devoted his energies without remuneration to organizing barrio high schools and community colleges. With support from the Department of Education and enthusiastic participation by local citizens this barrio high school movement has spread to 43 provinces and six cities.

Although establishment of barrio high schools alone is no panacea for our educational needs, it is a vital and positive move. Aware that a traditional society needs time for change, ORATA has insisted rural people want and are entitled to opportunities for schooling equal to those in the cities, while urging that the national curriculum be shaped more realistically to Filipino needs. Toward this goal of an educated citizenry he continues to persevere with patience and informed enthusiasm.

In electing PEDRO TAMESIS ORATA to receive the 1971 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Public Service, the Board of Trustees recognizes 44 years of creative work in education, particularly his conception and promotion of barrio high schools for rural Filipino youth.

I am unable to find the right words to express my gratitude for the honor which you have bestowed upon my humble self. All I can say is that I will do my utmost to continue deserving the Foundation’s confidence.

As I have said from the beginning of our work seven years ago, it has been possible to accomplish what we have done because of several very favorable conditions: first, the permissive atmosphere provided by the Department of Education, from the Secretary down to the Division Superintendents and their staffs; second, the wholehearted response and cooperation of the parents, students, and lay leaders who have worked very hard to provide the necessary financial support; and third, the backing of the President, Congress, governors, city and municipal mayors, barrio captains and councilmen, who invariably have put the interest of the people, especially the barrio (village) people, above all other considerations.

This being so, as I announced in Singapore, the Award really belongs to all the people who made it possible to operate the barrio high schools, community colleges and preschools—despite the opposition of vested interests. Very fortunately, these vested interests are now our allies because they, themselves, are benefiting from these projects in more ways than one, which need not be mentioned. The fact is that there is very little opposition to the continuation and extension of these projects. Our people—all of us—realize at last that unless we help the barrio people in their effort to lift themselves up, they will continue pulling us—all of the rest of us—down. Our well-being and welfare are dependent upon their having equal opportunity to develop their capacities to the utmost for the welfare of all.

It is for this reason that I have decided that every cent of the Award will be spent towards the extension of the projects, not only in the Philippines but abroad as well. The people in the remaining barrios that have no high schools have as much right to education at all levels as the ones in the 1,600 that have them now. What form the aid will take will be decided in due course, and you will be informed.

Again, permit me to thank you most sincerely for this Award and I hope I will continue to deserve your confidence.