- Theater has been his lifelong passion. As a young professor at the University of Ceylon, SARACHCHANDRA produced Sinhalese adaptations of Anton Chekov, Oscar Wilde, and Moliere. But Western plays, he decided, — never got to the roots of our people — He searched the villages for dramatic forms that did.

- His 1953 book, The Sinhalese Folk Play, led to a fellowship to study the dramatic arts elsewhere in Asia and the United States. Witnessing the vitality of Noh and Kabuki Theater in Japan, he yearned to resurrect classical Sinhalese drama for modern audiences.

- SARACHCHANDRA believes that his society’s most fundamental values remain endangered. The norms of today’s marketplace, he points out, are incompatible with Buddhist teachings and work against the survival of once hallowed traditions. Yet a healthy nation must live harmoniously with its past. SARACHCHANDRA, therefore, writes plays in form and content that transcend the present and speak to the permanent experience of his people.

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes his creating modern theater from traditional Sinhalese folk dramas and awakening Sri Lankans to their rich cultural and spiritual heritage.

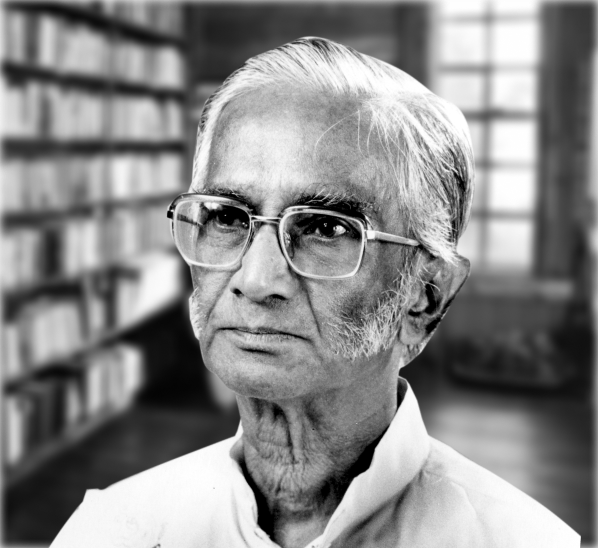

In much of Asia colonial rule weakened the traditional arts. Ruling classes and educated urbanites often favored Western ways. Old forms of drama, music, and dance withered, and powerful cultural moorings were lost. In Sri Lanka this process occurred over four centuries. By the 1950s only the villages kept the old traditions alive. VEDITANTIRIGE EDIRIWIRA SARACHCHANDRA rediscovered them there.

SARACHCHANDRA first encountered the rich cultural life of Sri Lanka’s villages as a youth, moving from place to place with his father, a postmaster. Later he was inspired by India’s independence movement and by the works of Rabindranath Tagore, India’s great writer and poet. He qualified in Sanskrit, Pali, and Sinhalese at the University of Ceylon, and in Western philosophy at the University of London. In 1949 he received his doctorate in Buddhist Philosophy.

Theater has been his lifelong passion. As a young professor at the University of Ceylon, SARACHCHANDRA produced Sinhalese adaptations of Anton Chekov, Oscar Wilde, and Moliere. But Western plays, he decided, “never got to the roots of our people.” He searched the villages for dramatic forms that did.

His 1953 book, The Sinhalese Folk Play, led to a fellowship to study the dramatic arts elsewhere in Asia and the United States. Witnessing the vitality of Noh and Kabuki theater in Japan, he yearned to resurrect classical Sinhalese drama for modern audiences.

In his 1956 play Maname, based on a well-known Buddhist myth, characters sing and speak rhythmic prose. A narrator and chorus comment on the story. Drums, cymbals, songs, and dances are used throughout. There is no set. Maname’s sensational reception established SARACHCHANDRA’s “stylized play” as a popular genre. A stunning revival of Sinhalese theater followed and Sinhalese dance and music were given new life.

SARACHCHANDRA continued experimenting. His 1961 masterpiece, Sinhabahu retells the Sinhalese origin myth. Pemato Jayati Soko, of 1969, is an opera set to North Indian-style music. Altogether he has written more than twenty-four plays. Maname alone has been performed some three thousand times.

Renowned as Sri Lanka’s premier playwright, SARACHCHANDRA is also a prolific literary critic who has set new standards for Sinhalese writing. His own novels and short stories offer trenchant commentary on contemporary life. On social and political issues he speaks his mind fearlessly and often. From 1974 to 1977 he was Sri Lanka’s ambassador to France. This experience prompted his English-language novel, With the Begging Bowl, depicting the plight of money-poor Third World diplomats.

Formally retired from the university, today seventy-three-year-old SARACHCHANDRA is director of the Sarvodaya Research Institute. A commission of scholars under his leadership is now investigating the deterioration of Sri Lanka?s social fabric since independence.

SARACHCHANDRA believes that his society’s most fundamental values remain endangered. The norms of today’s marketplace, he points out, are incompatible with Buddhist teachings and work against the survival of once hallowed traditions. Yet a healthy nation must live harmoniously with its past. SARACHCHANDRA, therefore, writes plays in form and content that transcend the present and speak to the permanent experience of his people.

In electing VEDITANTIRIGE EDIRIWIRA SARACHCHANDRA to receive the 1988 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Journalism, Literature, and Creative Communication Arts, the Board of Trustees recognizes his creating modern theater from traditional Sinhalese folk dramas and awakening Sri Lankans to their rich cultural and spiritual heritage.

On this occasion, which is indeed the most memorable in my life and career as a writer and academic, I recall that when I first set out in 1955 in my search for a native idiom in the theater, or at least an Asian model, the first country that I visited was the Philippines. Here I got acquainted with the experimental work of Severino Montano whose Arena Theater movement was evoking great interest among theater-lovers, and I had the opportunity to get to know something of Philippine folk theater forms like the moro-moro. I was also fortunate to have made friends with several young writers who have since become distinguished personalities in the literary world. At that time I did not imagine, even in my wildest dreams, that I would return after these many years, to be honored by this most prestigious award for the work that I began then, and be welcomed so warmly by a nation that, inspired by the spirit of that great leader, President Ramon Magsaysay, has shown such heroism, unity, and determination in the fight against despotism and has earned, thereby, the admiration and respect of the whole world.

One of the most difficult and, to my mind, the most important of the problems that the countries of the Third World have to face, particularly if they have a history of colonialism, is how to reconcile their system of traditional values with the values of industrial civilization, which are materialistic. Most programs of development that the governments of the Third World are embarked on result, either as a by-product of their endeavors or as an avowed aim, in the transformation of their societies into consumer societies and the initiation of their people in the lifestyle of the people of the affluent industrialized nations.

The values of the consumer society are, in many respects, diametrically opposed to the values of traditional societies and the values of all the higher religions. I think you will admit that it is, to say the least, inadvisable for any program of development to ride roughshod over the values that have guided a society for centuries and have contributed to its cohesiveness. We have seen how such a neglect of traditional values has resulted, in some instances, in moral chaos and in the total upheaval of societies. Industrial civilization inculcates, as its highest value, the pursuit of pleasure. Apart from the fact that experience shows hedonism does not bring total satisfaction to people, it is relevant to ask ourselves whether the resources of our countries or of the world will ever permit any but the very few to enjoy the lifestyle of the people of the affluent nations. Politicians are often not aware of such problems or do not wish to give weight to such considerations because they want quick results. Hence, they concentrate on material development without realizing that material development must be geared to the values of a culture. It is these values that will dictate what kind of development would produce wholesome results, that would bring about a pattern of life that would give material as well as spiritual satisfaction to a people. In order to achieve this, there must be a constant dialogue between intellectuals and politicians.

Today, when my lifework has been deemed worthy of recognition by such a highly esteemed body as the Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation, I like to look back for a moment and ask myself what were the motives, both conscious and unconscious, that have inspired me.

I drew material for my plays from a body of myth and legend that has been current among my people for some two thousand years and has influenced their attitudes and actions. I was hoping to get at the roots of our culture, at the roots of people?s thinking, at the racial unconscious, so to say, and to remind people of the fundamental values that have formed the basis of our culture, values that four centuries of colonization have nearly wiped from memory. But I have not advocated in my plays an uncritical acceptance of these values. The subtext, which is often not apparent to the average playgoer, suggests that some values of a feudal culture are not consistent with modern man’s attitudes and should be discarded. As an example, I would like to mention the attitude toward women that finds expression in some of these legends. The values that are valid for all time are sympathy for human suffering, sympathy for the oppressed and downtrodden, and a sympathetic understanding of the human condition. These are values that transcend all limitations of time and place.