- Called to head Malaysia’s court system as Lord President in 1974, SUFFIAN’s lifelong pursuit of fostering both better government and better citizenship has become the foundation of his work in the judicial sector.

- He authored several books on Malaysia’s constitution, written in fairly simple language, which was aimed at the wide public outside the university and the courtroom. The Government relies upon him to head commissions on controversial issues, knowing a careful study will be made on time and his findings will be trusted.

- He searched for a new legal synthesis that truly will make Malaysia a harmonious society, guiding the university system to relevance, speaking with a voice of moderation, and provided a model of what can be accomplished for the public good through dedicated service to governments.

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes his uprightness and humanity in adapting Western legal forms to realities of his own plural Asian society and shaping the public institutions of a new nation.

Law is the cement of enduring civilizations, codifying aspirations of a people for their mutual well-being. The law thus must supersede the individual, yet, in its framing and interpretation, sensitivity to personal needs and simple justice are requisite for its continued acceptance. Especially is this so when diverse customs and values must be welded to shape a common national identity.

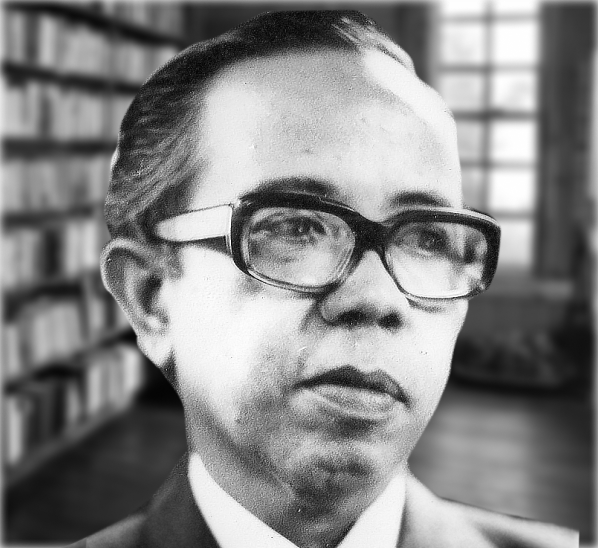

Tun SUFFIAN’s career parallels the emergence of Malaysia. Born in 1917 into a humble family in a kampong in the northern Malayan state of Perak, he was the first pupil of any rural school to win a Queen’s Scholarship. Study in England at Cambridge University was followed by call to Bar at the Middle Temple, London in 1941. En route back to Malaya, the Japanese occupation of his homeland caught him in Ceylon. Joining the war effort he began broadcasting to Malaya for All India Radio and later for the British Broadcasting Company.

The end of hostilities prompted SUFFIAN’s return to England to study public administration and social anthropology at the London School of Economics, before joining the Malayan Civil Service. Named Magistrate of Malacca in 1948, he also served as Harbor Master. Throughout the difficult years of the Emergency he was posted to such city and state positions as Federal Counsel, Public Prosecutor, Solicitor-General and Constitutional Adviser in Kuala Lumpur, Johore Bahru, Brunei and Pahang. He learned to know broadly his people and their problems. While serving as High Court Judge in Alor Star in 1964—after creation of the Federation of Malaysia—he was appointed Pro-Chancellor of the University of Malaya, and the following year became Chairman of the Royal Commission on Salaries of the Public Service.

Called to head Malaysia’s court system as Lord President in 1974, SUFFIAN’s life long pursuit of fostering both better government and better citizenship has not slackened. His book on Malaysia’s constitution, written in fairly simple language, was aimed at the wide public outside the university and the courtroom. The Government relies upon him to head commissions on controversial issues, knowing a careful study will be made on time and his findings will be trusted. Withal, in deportment and concern he has retained a sense of his simple beginnings, advising others in high office not to be dazzled by prestige.

Searching for a new legal synthesis that truly will make Malaysia a harmonious society, guiding the university system to relevance, speaking with a voice of moderation, SUFFIAN gives form to his motto, “life is service.†For the young of his nation he has provided a model of what can be accomplished for the public good by following this precept.

In electing Tun MOHAMED SUFFIAN BIN HASHIM to receive the 1975 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Government Service, the Board of Trustees recognizes his uprightness and humanity in adapting Western legal forms to realities of his own plural Asian society and shaping the public institutions of a new nation.

My wife and I are delighted to be here today to receive the Magsaysay Award. It came out of the blue on Saturday 3 August when at about 5:00 p.m. a friend in Kuala Lumpur rang me up at home to say that he heard announcement of it on TV a few minutes earlier. The Award came as a great and pleasant surprise.

Your late President Ramon Magsaysay cared for people and believed in the dignity and importance of the individual. He strove to improve the lot of his countrymen. He had courage, he had conviction. His ire was aroused whenever he saw injustice. He believed that freedom should be enjoyed by all. I shall strive to live up to the ideals that inspired him.

The Award is a great honor to me, personally, and I cannot express how happy I am to be in the distinguished company of so many eminent men and women who have been similarly rewarded, especially when I remember that two of the five Malaysian recipients were Prime Ministers.

The Award is, however, a greater honor to the judiciary of this region than to me personally, for you have never before honored a judge. I am very proud that I am the first and may I express the hope that I won’t be the last judge to win this Award.

In a developing country like Malaysia we are dependent on agriculture, fishing and other peasant activities which bring little reward in terms of material things, and our various governments do the right thing by bending their efforts towards fostering and increasing industries and manufactures so that we get more return for our labor and spread the good things of life among more and more of our people. So the emphasis, certainly in my country, has been to produce more and more economists, accountants, bankers, manufacturers; more and more engineers, architects, surveyors; more and more doctors, dentists, scientists, and so on, people whose efforts can result in increasing our bread and butter. Though during the struggle for independence lawyers were most courageous and skillful fighters and were always to the fore, yet after independence, apart from the few lawyer-politicians who man the cabinet and the legislature and the civil service, the importance of the legal profession has been eclipsed by the importance of citizens who fell the forest and till the soil; who build roads, bridges and houses; open and run schools, universities, hospitals, and clinics, and open and run factories, banks, insurance companies, and the like, persons whose efforts visibly increase the GNP and generally help the citizenry to a better and more prosperous life. In Malaysia during the period after independence the legal profession, as such, has occupied a back seat, and its role has never caught the public imagination.

Practising lawyers are themselves to blame for the comparatively insignificant part they are playing during the most formative stage in the history of our developing country. They tend not to see the wood for the trees, and in the endeavor to serve their client’s interest they get lost in a jungle of technicalities and forget that the law is also an instrument to be used for the general improvement of the community. The law is not something immutable, something carved on tablets of stone that cannot be changed. The law should serve man, not man the law, though of course man must obey it until it has been changed if we are to avoid anarchy. My philosophy is quite simple: having read in history books that the law can be used as an engine of oppression, we should, on the contrary, determine to use it as an instrument to improve the lot of mankind, as an instrument for bringing about a good and just government in a system whereby it is possible for us to choose the persons who decide our present and future and to change them at periodic intervals through the ballot box rather than the bullet.

Government is responsible for making the law, and governments try to enact just laws, but laws are made to suit the times, and when times change sometimes the law ceases to be just in its application to actual cases. I have always held the view that it is the public duty of every lawyer to bring to the notice of the authorities instances of antiquated laws so that they may be amended and brought up to date, in line with new circumstances and modern ideas of what is and what is not just. This is especially important in a newly independent country.

Having dealt with lawyer-politicians who make the law, and lawyers who practice the law, I now turn to judges. Their role in the courtroom is well known and there is no need for me to say anything about it. Today I would rather talk of the extracurricular activities of a judge. He should eschew partisan politics and not indulge in public controversies. His judgments are often reported in the daily papers, and are accepted for their impartiality. Accordingly, he enjoys a special place in the community, being regarded as fair-minded and not swayed in a multiracial and multi-religious country by racial and religious considerations, being guided simply by what is just. Enjoying the confidence of the public, outside the courtroom he should be ready to perform community functions—serving on a school board, or in any other educational capacity, doing work among young people, serving the Red Cross—and the Government may call upon him to serve on or head a Commission of Enquiry. The last is particularly true of Malaysia where everytime the Opposition demand a public enquiry they always stipulate that it be led by a High Court judge. The judiciary is naturally proud of the confidence shown by the public in our sense of fair play. My attitude has always been to accept whatever assignment is thrust upon me beyond the line of duty, provided that there are no political overtones to the assignment, for nothing harms the judiciary more than being involved, or thought to be involved, in partisan politics. No matter how humble his origin, when a person has become a judge he belongs to a privileged community and it is his privilege to serve the community in any capacity not inconsistent with his judicial office.

I am lucky in having been invited to serve the community outside the courtroom in several capacities. Other Malaysian judges have also been similarly lucky, but I am luckier than all of them, because my activities came to the notice of your trustees with very pleasant results indeed to my wife and me, for it has enabled us to visit your great country and meet so many interesting and wonderful people.