Events engulfing Vietnam over the past three decades have compounded the dilemma of concerned intellectuals seeking sources for their national inspiration. Traditionally schooled in Nho hoc, or Confucian learning, they were cut adrift from their origins by the system of education that accompanied French colonial rule. As this elite was oriented toward French, it lost touch with the peasantry and left them vulnerable to Communist persuasion.

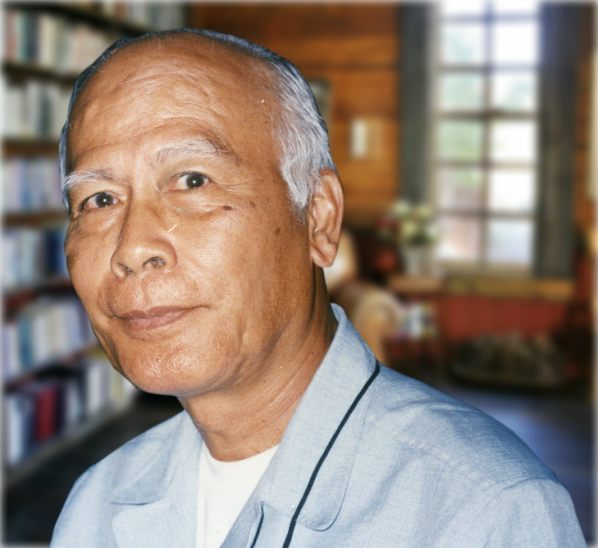

Minister TON THAT THIEN, by contrast, relentlessly has sought to digest the essence of Western scientific method and wed it to Vietnamese cultural values. Freedom of thought and expression he found were essential to this pursuit. His convictions led him to act with perceptive courage and staunch individualism as writer and editor, professor and government official.

Born in Central Vietnam in 1924 THIEN from early youth was steeped in the history and classical teachings of his country. After World War II he earned a degree at the London School of Economics. Graduate work at the Institute of International Studies in Geneva was interrupted by a call to join the Vietnamese delegation at the 1954 conference that led to independence for his country.

THIEN enlisted promptly in the new government in Saigon, serving as Press Secretary to the Premier. Differing later with the authoritarian conservatism of the Diem regime, he left to complete doctoral studies in Geneva. Unlike other disaffected idealists who found haven abroad, he returned in 1963 to serve as Director General of Viet Nam Press. Moving to private journalism as a political columnist on the Saigon Daily News, he went on to found with like-minded colleagues the Viet Nam Guardian, becoming its managing editor.

When the Guardian was suppressed in December 1966 THIEN continued to write for the London Economist, The Far Eastern Economic Review and Forum World Features, among others. He also taught and in 1967 became Vice Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences of Van Hanh University, where he helped organize the study group that is probing Vietnam’s past for guides to the present.

With the appointment of Tran Van Huong as Premier in April 1968 signaling more popularly responsive government, THIEN accepted the post of Minister of Information. His first act upon assuming office was to lift press censorship, explaining: “Why have 25,000 Americans and more than 100,000 Vietnamese died in this war, if not for freedom?”

In electing TON THAT THIEN, editor and now Minister of Information of the Republic of Vietnam, to receive the 1968 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Journalism, Literature and Creative Communication Arts, the Board of Trustees recognizes his enduring commitment to free inquiry and debate.

I deeply appreciate the very great honor you have done me by associating me with the name of one of the greatest sons, not only of the Philippines, but also of Asia. Ramon Magsaysay is an Asian, and a nation builder no less great than such men as Meiji of Japan, Mongkut of Siam, Sun Yat-sen of China, Gandhi of India, and Phan Boi Chau and Phan Chu Trinh of Vietnam. He belongs to that breed of men of whom every Asian feels immensely proud.

“It has been my great fortune to have met the late President Magsaysay in December 1956 and to have watched him working for the freedom and the uplifting of his people. I was received by him in his office at Malacanang, and I could see that this office was crowded with people from the barrios seeking redress. I realized that they would not have come there if they did not trust him and if he had not seen to it that they could reach him freely. That was an image which has remained deeply imprinted in my mind. Thus, President Magsaysay has been a source of inspiration to me. As a social scientist and one committed to social reforms in Vietnam, I have learned much from the work done by President Magsaysay for his people, and especially from his motivations and his style. One could not watch him go about his work, even when one did so from afar, without being struck by his lack of concern for what other people might say about him or do to him. He was only concerned about the freedom of his people, and he realized that there could be no real freedom for the Philippines unless every Filipino, especially those from the barrios, could freely make his voice heard, either in seeking redress, or in contributing suggestions for the improvement of the government of the country. President Magsaysay understood that there could be no real freedom for his people unless they were given the opportunity of acquiring knowledge through education and free access to information. Being one of those in Vietnam who share President Magsaysay’s ideals, philosophy, and determination to work for the social transformation of my people”

“I confess that I was highly pleased on being told that I had won an award associated with Magsaysay’s name, and especially with what he stood for. I am only one of many, among whom is my friend and editor of the Viet Nam Guardian, Nguyen Van Tuoi, who have been encouraged to persist in this undertaking not only by the memory of President Magsaysay, but also by the example of a man who, to me, is a living image of President Magsaysay in Vietnam. That man is our present Prime Minister, Tran Van Huong, whose origin, life, ideals and determination that Vietnam shall not fall under communism, are so similar to those of the great man from Zambales”.

Mr. Tran Van Huong was born into a very poor family; in fact he was the son of a kitchen hand. But he has risen to his present position by sheer force of will and an unshakable determination to acquire a good education. Like President Magsaysay, he is motivated by a deep love for his country and people and fully realizing that the quality of a nation is the sum of the qualities of its citizens, he is determined to see to it that all Vietnamese are given the opportunity to acquire freedom and knowledge in order to uplift their country.

Without Mr. Huong, I would not have the chance of turning into reality a long-cherished dream: that of contributing actively and effectively to the enlargement of freedom in Vietnam and in Asia, and of adding my share to the fight for freedom being waged everywhere in the world. Today, freedom, like prosperity and happiness, is indivisible. The Magsaysay Award Foundation should remind us all of that truth.