- During China’s Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), YING was jailed for three years and then sent to the countryside to plant rice with other artists and intellectuals. His re-education lasted ten years; thereafter, he returned to the People’s Art Theater and reestablished his career.

- He translated into Mandarin Shakespeare’s “Measure for Measure†and other Western works for Chinese audiences. In turn, as a visiting professor at the University of Missouri in the U.S., he staged Chinese plays for American audiences, including his own translation of Ba Jin’s modern classic, “The Family.â€

- 1983 was the production in Beijing of YING RUOCHENG’s acclaimed translation of Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman,†with YING playing the lead role and Miller himself directing.

- As chair and president of the China Arts Festival Foundation, YING carries on his work nurturing China’s theater arts exposing Chinese audiences to plays and performances from abroad.

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes his enhancing China’s cultural dialogue with the world-at-large and with its own rich heritage through a brilliant and persevering life in the theater.

YING RUOCHENG’s childhood home near the Forbidden City in Beijing stood next door to the city’s Roman Catholic Cathedral—a fitting location since the family was both Manchu and Christian. It was also an intellectual family. YING’s reform-minded grandfather founded Beijing’s Catholic Furen University; his father, who was English-educated and went by the name of Ignatius, later lectured there. YING Ruocheng himself was born in 1929. China’s struggle with Japan and its great civil war framed his entire youth. By the time he completed a degree in Western Literature at Qinghua University in 1950, communism had triumphed. YING was hopeful. At the time, he wrote years later, “China was full of dreams.â€

Theater was his love. In 1952, he and other young artists founded the Beijing People’s Art Theater to transform drama in light of the country’s bright hopes. In heady years of experimentation, YING mastered his craft in Chinese and Western plays. The Cultural Revolution caught the People’s Art Theater in a dangerous power struggle. YING was jailed for three years and then sent to the countryside to plant rice with other artists and intellectuals. His re-education lasted ten years. When the mayhem subsided, he returned to the People’s Art Theater and reestablished his career.

A period of remarkable productivity followed. YING appeared in play after play and explored anew the East-West dialogue that had engaged him since his youth. He translated into Mandarin Shakespeare’s “Measure for Measure†and other Western works. As a visiting professor at the University of Missouri, he staged Chinese plays for American audiences, including his own translation of Ba Jin’s modern classic, “The Family.†He also appeared as Kublai Khan in an English-language television series. Then, in 1983, a seminal event: the production in Beijing of YING RUOCHENG’s acclaimed translation of Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman,†with YING playing the lead role and Miller himself directing. The play’s flawed hero and moral ambiguities stood in sharp contrast to the morality tales typical of China’s official theater at the time. Yet YING knew that the story of a family in crisis would speak to Chinese audiences. Moreover, a play about the failure of the American Dream also spoke to the dreams of his own generation in China. These, he said, had disintegrated in the Cultural Revolution.

Between 1986 and 1990, YING served as vice minister of culture. His office embraced three thousand government-supported arts troupes. Striking a blow against bureaucratization, YING reduced or ended many government subsidies and initiated other reforms to promote independence and artistic freedom. The effect was bracing. Standing on their own, theater companies were free to make money or go bankrupt. Although YING made enemies in the post, China is now reaping the rewards of his bold reforms.

YING’s ability to work in both the Chinese and Western mediums has made him something of a cultural ambassador. And of course he is famous now, having appeared prominently in films such as Bernardo Bertolucci’s “The Last Emperor†and “The Little Buddha†and in other English-language movies and television programs.

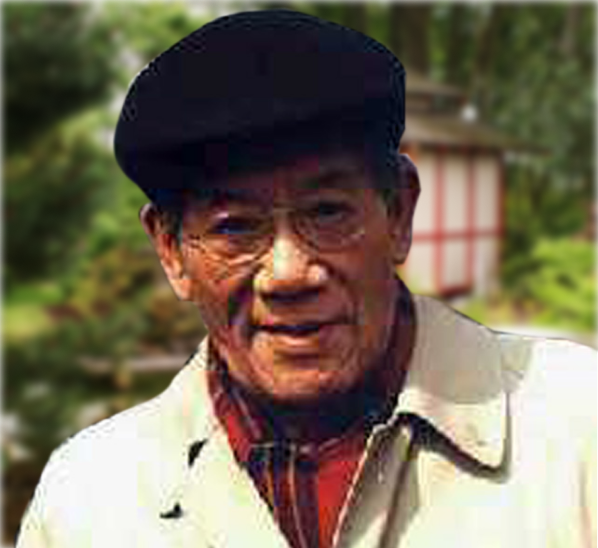

Today, as chair and president of the China Arts Festival Foundation, the tall, urbane YING carries on his work nurturing China’s theater arts and exposing Chinese audiences to plays and performances from abroad. There are still a lot of stereotypes to break down, he says. Yet the key to a successful inter-cultural exchange is simple. It is treating the work of others “with respect, with understanding, and with commitment.â€

In electing YING RUOCHENG to receive the 1998 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Journalism, Literature and Creative Communication Arts, the board of trustees recognizes his enhancing China’s cultural dialogue with the world-at-large and with its own rich heritage through a brilliant and persevering life in the theater.

On this auspicious occasion I wish to thank the trustees of the Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation for choosing me as one of the recipients of this prestigious honor. It is especially gratifying for me and my colleagues as the award is a tangible justification for our efforts at enhancing creative communication among the peoples of the world. In such a context I would like to consider the award not just as my personal accomplishment but a token of esteem for all my colleagues and co-workers who made this possible.

China, in her long and continuous history, has always been self-contained and used to consider herself the center of the world. As a result, she had a reputation of inscrutability. Attempts to open her up by force in the past have failed, leaving regrettable casualties and bad feelings. One of the most important factors in present day international relations is the end of isolation for nearly one-quarter of mankind. China’s doors are now open. The significance of such an epochal event is that her doors were not opened by force, but by a consensus of the Chinese people themselves who have summed up their historical experiences and come to the conclusion that China should open her doors to the rest of the world. Because this is a consensus, arrived at by the highest leaders of the country as well as the man in the street, there is no going back. To reform the system and open up the country have become the basic policies of the PRC. China not only opens her doors, but her arms as well.

It is with such a background in mind that I am here to receive this honor. My greatest wish is it may help consolidate the friendship between China and the Philippines.