- He discovered a wild-rice variety in 1970 which led to a breakthrough research in hybridization of rice, and with the robust support of the Chinese government, YUAN now led a nationwide team of researchers to develop in 1974 the “three-line hybridization system,” capable of producing high-yield hybrid seeds on a commercial scale.

- YUAN’s research center has already trained 350 scientists from twenty-five countries. His hybrid rice technology is raising hopes for food self-sufficiency in Vietnam, India, the Philippines, Myanmar, Bangladesh, and other Asian countries.

- His continuing research offers even more promise for world food security and adequate nutrition for the world’s poor.

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes the unique contribution of his research in rice hybridization to food security in Asia.

Rice is Asia’s staple food, the delicious grain upon which its civilizations have grown and flourished since earliest times. Over centuries, Asia’s farmers toiled to render forests into rice fields and tinkered endlessly to garner from each paddy and stalk just a little more rice. Rising populations in modern times have meant that more rice must be grown on less land, especially in China where people now number over a billion. YUAN LONGPIN, director general of the China National Hybrid Rice Research and Development Center, has confronted this urgent need. His brilliant innovations in hybridization offer hope that, in the years to come, there will always be enough rice.

As a boy during the Japanese War, YUAN followed his father across China to Chongqing, attending one school after another. An eager learner, he earned the nickname “Questioning student.” A visit to a horticultural garden awakened in him a love for plants. He studied agriculture in college and, as a young teacher at Anjiang School of Agriculture in Hunan, began his own experiments in crop breeding. Shocked by China’s great famine of 1958-1961 and by the impoverished life of rural villagers, YUAN devoted himself to developing higher-yielding rice plants. Thwarted by flawed Soviet theories and by the Cultural Revolution, he persisted despite disappointments and risks. Quietly shifting to sounder genetic models, he began to succeed.

Hybridization held the key to unleashing the power of heterosis-the dramatic growth spurt that follows the crossing of genetically distant parent plants. Yet hybridization on a large scale seemed beyond the reach of plant scientists. By the early 1960s, many had abandoned the search. YUAN carried on, publishing a key scientific paper in 1966. The discovery of a naturally sterile male wild-rice variety in 1970 led to a breakthrough. With the robust support of the Chinese government, YUAN now led a nationwide team of researchers to develop in 1974 the “three-line hybridization system,” capable of producing high-yield hybrid seeds on a commercial scale. Able to yield 15-20 percent more rice per hectare than the best non-hybrid varieties of the time, YUAN’s new seeds spread rapidly in China.

As a consequence, China’s rice production rose by 47.5 percent by the 1990s, even as some five million hectares of erstwhile paddy land was shifted to cash crops such as vegetables, fruits, cotton, and rapeseed. Meanwhile, at his research center in Changsha, YUAN raced to simplify and improve his technique, achieving a higher-yielding two-line system in 1996. Today, half of China’s rice land is planted to YUAN’s hybrids. At the same time, the business of hybrid seed production is raising incomes across the countryside.

These days YUAN is perfecting what he calls super-hybrid rice, to yield 25-30 percent more than current hybrids. “If this materializes,” he says, “we can feed 100 million more people.”

YUAN’s research center has already trained 350 scientists from twenty-five countries. His hybrid rice technology is raising hopes for food self-sufficiency in Vietnam, India, the Philippines, Myanmar, Bangladesh, and other Asian countries. All of this delights YUAN, who says, “One of my dreams is to make hybrid rice help more people in the world.”

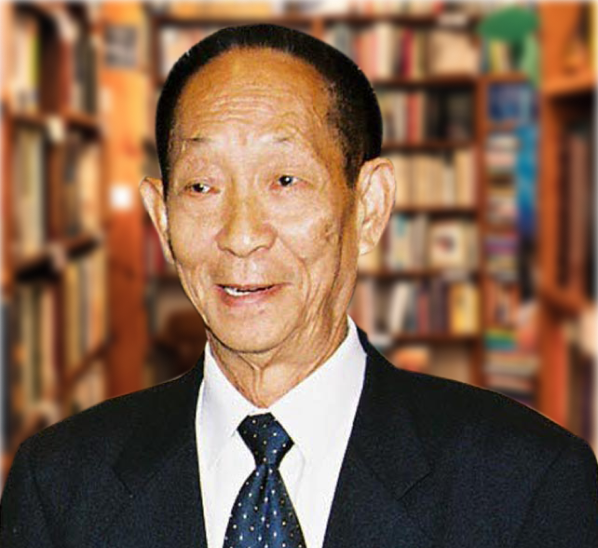

Lean and wiry at seventy years and still hard at work, Yuan is a man of simple ways who rides a motorcycle to the fields daily and dresses like a farmer. He has enriched the lives of millions of Chinese villagers, who revere him and call him the Father of Rice. YUAN returns the compliment. “The peasants in our country have a very rich experience in how to grow rice,” he says. “I have a lot to learn from them.”

In electing YUAN LONGPIN to receive the 2001 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Government Service, the board of trustees recognizes the unique contribution of his research in rice hybridization to food security in Asia.

Your Excellency President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, members of the Magsaysay Family, distinguished guests, trustees, fellow awardees, ladies and gentlemen:

It is my great honor and pleasure to attend this glorious ceremony to accept the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award.

First, I would like to express my hearty thanks to the Board of Trustees of the Foundation for recognizing the important role of hybrid rice in raising food yield and for setting a high value on my work in this research field.

The success in the development of hybrid rice is a major breakthrough in rice breeding, providing an effective approach to increase rice yield by a big margin. In recent years, about 16 million hectares of paddy field are cultivated with hybrid rice each year in China. The average yield of hybrid rice is 7 tons per hectare which outyields the conventional pure line varieties by more than 1.5 tons per hectare.

Our experiences showed that expansion of hybrid rice area is a most efficient and economic way to increase grain yield. At present, there are some 150 million hectares of rice in the world and the average yield is only 3 tons per hectare. According to FAO’S data, the acreage under hybrid rice in 1990 was 10% of the world’s rice area, but it produced 20% of total rice production. From this we can roughly calculate that if conventional rice were completely replaced by hybrid rice, total rice production in the world would be doubled, and this could meet one billion more people’s food requirements. Therefore, speeding up the development of hybrid rice in the world will be helpful to solve the starvation problems facing mankind.

There is no national boundary in science. Hybrid rice technology belongs not only to China but also to the whole world. For the welfare of people all over the world, I will continue to do my best to promote the development of hybrid rice in and outside China, especially in developing countries. Let hybrid rice make greater contributions to the whole world.

Thank you.