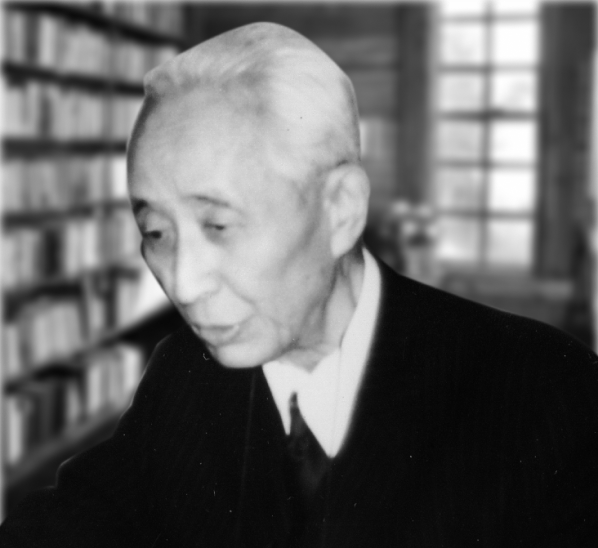

- More than 30 years ago JIRO KAWAKITA began studying the disintegrating environmental equilibrium of Nepal?s Sikha Valley, located west of Pokhara below the snow-clad peaks of the Himalayas.

- Discovering that government funds were not readily available, KAWAKITA and his associates established the Association for Technical Cooperation to the Himalayan Areas.

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes his winning the participation of remote Nepalese villagers in researching their problems, resulting in practical benefits of potable water supplies and rapid ropeway transport across mountain gorges.

Foreign scholars studying village life throughout Asia learn much of value which is shared, particularly with their peers. Frequently they also develop enduring personal relations among families with whom they live and learn. These cultural anthropologists, sociologists, economists and others contribute to the growing intellectual milieu of one world.

With only rare exceptions, however, the villagers who have hosted research scholars and offered insights into their cultures receive little or nothing in return. After the dissection of their life-styles, problems and aspirations, these usually friendly folk may be left even more discontented by an awakened awareness of unattainable possibilities.

More than 30 years ago JIRO KAWAKITA began studying the disintegrating environmental equilibrium of Nepal’s Sikha Valley, located west of Pokhara below the snow-clad peaks of the Himalayas. Population pressure upon scarce land was compounded by modernizing demands of retired veterans of Gurkha regiments and seasonal laborers who worked abroad. Forests were being destroyed as need for livestock forage and human food compelled enlargement of ever-higher hillside fields. Focusing upon high-elevation terraced culture of barley, wheat, maize and African millet, KAWAKITA complemented his ethnogeographic research with mountain climbing. Crossing over mountain crests and through gorges gave him a vivid appreciation of villagers’ hardships. He also designed an information analysis system which he used to help villagers identify their most urgent problems. This system he patented and it is used today by Japanese corporations for business planning.

Impelled by the plight of these some 5,000 Sikha Valley villagers, KAWAKITA in 1963 decided to find technological answers to their two priority needs: transporting fuel and forage down steep slopes to their homes, and securing drinking water without carrying it many kilometers across rugged mountain terrain. Extended discussions with Japanese technicians led to the choice of two simple technologies. The first was a wire ropeway similar to that used by tangerine growers in Japan to move harvests from hillside orchards. In Nepal it would need to be much longer, lighter, of greater tensile strength and highly durable to cross deep chasms and withstand harsh weather. The second was a hard polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipeline to carry water to villages without cutting into the fragile schist structure of the mountainsides.

Discovering that government funds were not readily available, KAWAKITA and his associates established the Association for Technical Cooperation to the Himalayan Areas. After soliciting contributions from individuals and corporations — sometimes in kind — and enlisting volunteers, they flew their wire rope, plastic pipe and supplies to Pokhara. With the help of the villagers who had participated in all the decisions, these eight tons of materials were carried four walking days over an arduous mountain trail to the Sikha Valley. The villagers helped install, and quickly learned to operate, the ropeways which greatly eased transport of fuel and forage from distant slopes. The pipeline has become a model for programs of the Royal Government of Nepal and UNICEF. A superhydro pump, whereby a stream fall of four meters lifts water from 120 to a maximum of 200 meters, did not prove durable in the Sikha Valley. At Nepalese government request this hydraulic ram that worked well for five years is being further tested in a village near Kathmandu to determine the required technological improvements and maintenance system.

As vital as easing the daily lot of the five Sikha Valley villages, is the development of binational relations between Japan and Nepal, and the new awareness of villagers that beneficial technologies are attainable without endangering their cultural environment. KAWAKITA has shown that the skills of human perception of ethnogeographers and other research scholars can be used to bring technology appropriate to their needs to the villagers they study.

In electing JIRO KAWAKITA to receive the 1984 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Peace and International Understanding, the Board of Trustees recognizes his winning the participation of remote Nepalese villagers in researching their problems, resulting in practical benefits of potable water supplies and rapid ropeway transport across mountain gorges.

It is my great honor to be given this noted Award which commemorates such an esteemed man as the late President Ramon Magsaysay. I am told he loved the common people and served them with the full strength of his energetic personality. My challenge in the Himalayas was also directed to the welfare of the common people, those who live in a remote area of those mountains; naturally I sympathize with his way of thinking. The honor of this Award, however, extends not only to me, but also to every participant who joined my project. Without their efforts, surely I would have accomplished nothing.

The aim of our project was to develop a concept of international technological cooperation, in particular directed to the revitalization of rural areas and based on self-reliance. Our motivation was not one of charity, but more that of a cheerful venture based on the spirit of mutual participation between the villagers concerned and my colleagues. The villagers gave their best willingly; consequently I learned many things through this experience. From this platform here tonight I want to say to them: “Thank you very much.” Their efforts moved us close to tears.

The mutual participation came from a common understanding of the total ecological and cultural environment. In other words, the participation was based on the holistic integration of qualitative data to achieve a scientific recognition of reality. In this sense, I believe, the way of true science coincides with the way of humanism. If this were not so, this so-called true science must be fundamentally reformed in the future.