- SINGH led Tarun Bharat Sangh (TBS, Young India Association), and organized villagers to repair and deepen old johads.

- He recruited a small staff of social workers and hundreds of volunteers and expanded his work village by village — to 750 villages today.

- He has introduced community-led institutions to each village where it manages water conservation structures and sets the rules for livestock grazing and forest use.

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes his leading Rajasthani villagers in the steps of their ancestors to rehabilitate their degraded habitat and bring its dormant rivers back to life.

Even in the best of times, it is arid in the Alwar district of Rajasthan, India. Yet not so long ago, streams and rivers in Alwar’s forest-covered foothills watered its villages and farms dependably and created there a generous if fragile human habitat. People lived prudently within this habitat, capturing precious monsoon rainwater in small earthen reservoirs called johads and revering the forest, from which they took sparingly.

The twentieth century opened Alwar to miners and loggers who decimated its forests and damaged its watershed. Its streams and rivers dried up, then its farms. Dangerous floods now accompanied the monsoon rains. Overwhelmed by these calamities, villagers abandoned their johads. As men shifted to the cities for work, women spirited frail crops from dry ground and walked several kilometers a day to find water. Thus was Alwar when RAJENDRA SINGH first arrived in 1985.

That was the year twenty-eight-year-old SINGH left his job in Jaipur and committed himself to rural development. With four companions from the small organization he led, Tarun Bharat Sangh (TBS, Young India Association), he boarded a bus and traveled to a desolate village at the end of the line. Upon advice of a local sage, he began organizing villagers to repair and deepen old johads.

When the refurbished ponds filled high with water after the monsoon rains, villagers were joyous and SINGH realized that the derelict johads offered a key to restoring Alwar’s degraded habitat. Once repaired, they not only stored precious rainwater but also replenished moisture in the soil and recharged village wells and streams. Moreover, villagers could make johads themselves using local skills and traditional technology.

As TBS went to work, SINGH recruited a small staff of social workers and hundreds of volunteers. Expanding village by village — to 750 villages today — he and his team helped people identify their water-harvesting needs and assisted them with projects, but only when the entire village committed itself and pledged to meet half the costs. Aside from johads, TBS helped villagers repair wells and other old structures and mobilized them to plant trees on the hillsides to prevent erosion and restore the watershed. SINGH coordinated all these activities to mesh with the villagers’ traditional cycle of rituals. Meanwhile, with others, TBS waged a long and ultimately successful campaign to persuade India?s Supreme Court to close hundreds of mines and quarries that were despoiling Sariska National Park.

Guided by Gandhi’s teachings of local autonomy and self-reliance, SINGH has introduced community-led institutions to each village. The Gram Sabha manages water conservation structures and sets the rules for livestock grazing and forest use. The Mahila Mandal organizes the local women’s savings and credit society. And the River Parliament, representing ninety villages, determines the allocation and price of water along the Arvari River.

Now, 4,500 working johads dot Alwar and ten adjacent districts. Fed by a protected watershed and the revitalizing impact of the village reservoirs, five once-dormant rivers now flow year round. Land under cultivation has grown by five times and farm incomes are rising. For work, men no longer need to leave home. And for water, these days women need walk no farther than the village well.

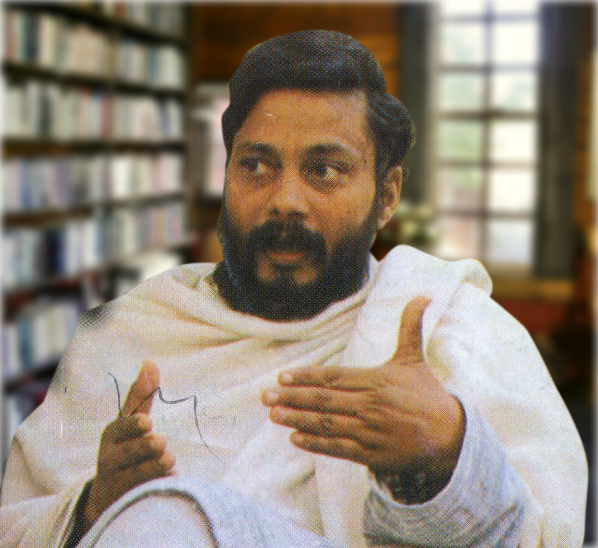

RAJENDRA SINGH is TBS’s charismatic motivator. Villagers call him Bai Sahab, Elder Brother, and listen to his every word. People have become greedy, he tells them. They should learn again to be grateful to nature. That is why, he says, in Alwar, “the first thing we do in the morning is touch the earth with reverence.”

In electing RAJENDRA SINGH to receive the 2001 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Community Leadership, the board of trustees recognizes his leading Rajasthani villagers in the steps of their ancestors to rehabilitate their degraded habitat and bring its dormant rivers back to life.

Your Excellency President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, trustees of the Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation, brothers and sisters, distinguished guests.

It is with great humility that I accept the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Community Leadership. This Award really belongs to those communities in Rajasthan in northern India, who have worked against tremendous odds to bring life back to their lands. They share this achievement with the men and women of the Tarun Bharat Sangh who have shown courage and determination.

Some 16 years ago when I arrived in Bheekampura village in Alwar District, we found that lack of water was driving young people away from theirhomes. Forced to abandon their families and the village, people had lost hope of seeing better days. The government had declared Alwar a ?dark? zone, meaning an area suffering from severe water shortage.

However, the elders in the villages still had among them the wisdom of their ancestors. Working side by side with TBS, they built traditional earthen dams known as johads. These small-scale, low-cost structures do not look like very much but taken together in hundreds and thousands, they have changed the face of this part of India. With water has come productivity, more income, a sense of community and a real feeling of self-reliance.

In 1996, we were amazed to find Arvari River flowing even at the peak of summer. We had been building water harvesting structures in the catchment area of Arvari over the years without realizing that we were in fact recharging the river through underground percolation. Since then 4 more rivers have become perennial.

With the arrival of water, problems of sharing arose. As a result Arvari Sansad (or River Parliament) came into existence representing 72 villages. This Parliament meets four times a year.

On another front, TBS had to wage a difficult battle against powerful marble mine owners who were destroying the ecology of the Sariska Tiger Sanctuary. Being located in the periphery of this Sanctuary, we filed a petition in the Supreme Court of India. While the case was on, I and my colleagues had to face continuous harassment and character assassination. The Supreme Court in its judgment vindicated our stand and over 450 marble mines were closed down in 1992.

I may mention that Mahatma Gandhi has a special place in my perception and ideas. He wanted every village to be self-reliant. Our efforts culminating in this Award are a small tribute to Mahatma’s vision and thinking.

Since being named a Ramon Magsaysay laureate, I have told my brothers and sisters back in India that this Award is a recognition of their untiring efforts. I have told them that the decision-making process leading to the building of johads can be replicated in other parts of India and in Asian countries where communities face similar challenges.

This Award will inspire communities of Alwar and other parts of Rajasthan where we work.

On their behalf, I am proud to thank you from the bottom of my heart. Thank you.