- JEI, after readmission to the university, was soon jailed for 11 months for antigovernment activities. Not long after he was released he and DALY decided to open a community center in two rented rooms in Yahng Pyeong Dong slum.

- With US$100,000 from MISEREOR, the German Catholic Social Aid Fund, and other monies from abroad, the two were able to purchase a small plot of land 12 kilometers southeast of Seoul only days before the eviction was to be carried out.

- The Board of Trustees recognizes their education and guidance of the urban poor to create vigorous, humanly sound satellite communities.

When South Korea’s effective modernization began a quarter of a century ago, it was geared to a manufacturing for export drive that stunned the trading world with efficient production of low cost goods. Disciplined laborers working harder, often for less, than anyone else in East Asia, were a key to this success. Unlike in Japan and Taiwan, where after World War II rural progress came first, in Korea villages felt the sweeping winds of change only a decade later. Hence seekers for employment and opportunity flocked to the cities, making Seoul one of Asia’s dozen largest cities and inevitably creating massive slums where social services lagged behind the need.

Life in a slum, though devoid of most amenities, still allows a sense of family warmth and home. Networks of relatives and co-workers cushion harsh outer realities. Now even this make-do haven is threatened by booming urban land values and both public and private redevelopment schemes that mean misery to evicted slum dwellers.

Thirteen years ago, Jesuit JOHN VINCENT DALY, a Sogang University philosophy professor, decided to learn how the poor viewed life by moving into Cheong Kyei Cheon, a Seoul slum. There he met PAUL JEONG-GU JEI, recently expelled from Seoul National University for leading demonstrations. Their first partnership in community concern lasted less than a year. JEI, after readmission to the university, was soon jailed for 11 months for antigovernment activities. Not long after he was released he and DALY decided to open a community center in two rented rooms in Yahng Pyeong Dong slum. Convinced that outside problem solvers tend to impose their perceptions, the two sought to be catalysts fostering community-determined change.

Three years later Yahng Pyeong Dong was classified for redevelopment. Little compensation or concern for their rehousing was vouchsafed the residents. Fifteen families approached DALY and JEI for help.

With US$100,000 from MISEREOR, the German Catholic Social Aid Fund, and other monies from abroad, the two were able to purchase a small plot of land 12 kilometers southeast of Seoul only days before the eviction was to be carried out. DALY, JEI, and the committee of slumdwellers which they had helped create, expected fewer but finally accepted 170 families. In May 1977 all but 20 of the families moved into tents on the new site and joined in building the village of Bogum Jahri, the Place of Happiness. With three skilled members as construction supervisors, and enthused by interdenominational prayer, the newcomers completed construction of the buildings by November 1977, and the sewage system for the 170 houses was finished by the onset of winter cold in December.

From such beginnings emerged a practical system for building housing at the equivalent of US$166 per pysong, or 3.3 square meters, largely with self-made construction materials which are one-third the cost of commercial materials. The second village was Han Dok and the third MokWha. A community center was constructed within walking distance of all three.

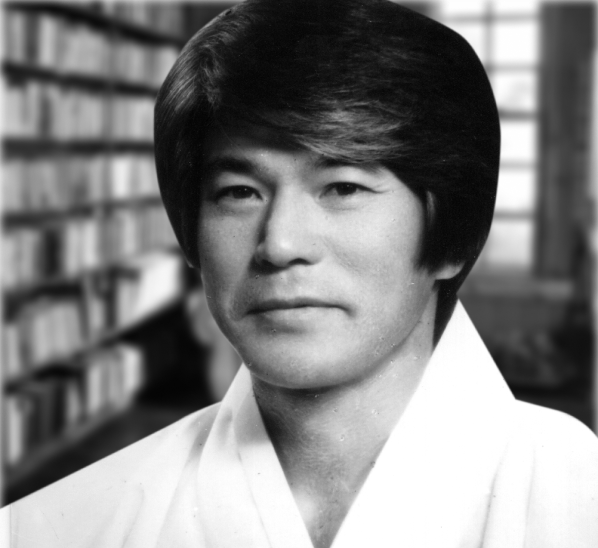

DALY, who was born in Philo, Illinois 51 years ago, has made South Korea his home for 26 years. Both he and his partner,JEI, who was born in 1944 in South Kyong-sang province, have become participants in the daily struggles of the homeless poor. They have established the Korean Catholic Research Institute of the Urban Poor to aid slum dwellers in learning their legal rights and correcting injustices such as unwarranted or unrecompensed evictions. The two are also attempting to prove that a rich cultural heritage can be retained and enhanced by the most disadvantaged, provided there is effective community organization and local leadership.

In electing Father JOHN VINCENT DALY and PAUL JEONG-GU JEI to receive the 1986 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Community Leadership, the Board of Trustees recognizes their education and guidance of the urban poor to create vigorous, humanly sound satellite communities.

After learning that I was recipient of the 1986 Ramon Magsaysay Award I was, for a few days, in a state of confusion. I thought to myself, I have already received my reward; how is it the Lord is giving me another? The reward I had already received was the ability to live as a poor man, not out of some kind of moral imperative or Christian sense of drag, but happy and content as a human being with other poor people; and I was also given the power to confront and challenge no matter what kind of suffering or persecution should follow—the powers of injustice which dehumanize the poor.

Since I considered these things my reward, I couldn’t see how or why the Lord would be giving me some other award. And I even began to worry a bit, wondering, what has been wrong in my life that He is giving me this very big and very prestigious Award.

But two days later I went to visit an area where people have been struggling and fighting against inhuman eviction, and as soon as I saw their ecstatic welcome and joy, at that moment I began to realize the meaning of this Award.

That is, before I saw this as an honor to me personally; now I saw it as a recognition of all poor people who long to be really human and who fight against violence and injustice. The absence of justice and the presence of structural and organized violence in the world is whet makes and keeps people poor, but even in their poverty, they do not forget, but rather cling to the value of the truly human.

And so, this Award is being given to me, not for some insignificant work or achievement, rather it is given because of a way of living.

Thus, I came to realize that this Award is not so much an award, but rather a ray of light to the countless numbers of anonymous companions who commit themselves to a similar way of living—accepting with joy and gratitude all kinds of pain and difficulties, being isolated and lonely, and receiving no recognition or acceptance from the world.

I am especially happy and grateful to receive this Award in 1986, the year in which the remarkable spirit and burning zeal of the late President Ramon Magsaysay blossomed, bore fruit, and empowered the Philippine people to attain democracy. Not “three cheers,” but ten thousand cheers for the Philippine people, and ten thousand “hoorays” for the fullness of humanity and for a more just and righteous world.