- MEHTA was drawn to environmental issues in 1984, when someone called his attention to the corrosive impact of air pollution upon India’s architectural masterpiece, the Taj Mahal.

- Meanwhile, when a gas leak at a fertilizer factory in 1985 killed several people and made nearly five thousand others sick, MEHTA won a landmark decision for damages.

- In similar MEHTA cases, the Supreme Court has ordered the Delhi Administration to relocate nine thousand dirty industries safely away from the crowded capital, to protect the city’s one remaining forest from illegal encroachments, and to build sixteen new sewerage treatment plants.

- The RMAF board of trustees recognizes his claiming for India’s present and future citizens their constitutional right to a clean and healthy environment.

In India, as elsewhere in Asia, laws to protect the environment have long been in place. Yet in India, as elsewhere, such laws are often honored in the breach, and flagrantly so. As a result, there is little to prevent the malignant discharges of the subcontinent’s polluting industries, its sewers, and its trucks and cars from fouling the air and water and earth—with crippling consequences for India’s crowded millions. India’s environmental agencies do have teeth, says crusading public interest lawyer M. C. MEHTA, “but they refuse to bite.â€

MEHTA was drawn to environmental issues in 1984, when someone called his attention to the corrosive impact of air pollution upon India’s architectural masterpiece, the Taj Mahal. He studied how effluents from nearby industries were eating into the soft marble of the shrine and filed a writ petition against the polluters with India’s Supreme Court. For more than ten years he pursued the case, marshaling mountains of facts. In a series of staggered directives, the Court responded by banning coal-based industries in the Taj’s immediate vicinity, by closing 230 other factories and requiring three hundred more to install pollution control devices, and by ordering the creation of a traffic bypass and a tree belt to insulate the unique monument.

Meanwhile, when a gas leak at a fertilizer factory in 1985 killed several people and made nearly five thousand others sick, MEHTA won a landmark decision for damages. And when someone inadvertently ignited the Ganges with a lighted match that same year, he filed petitions that led to orders against five thousand polluting industries along the holy river. At his insistence, 250 towns and cities in the Ganges Basin have been required to install sewerage plants. MEHTA vigilantly monitors compliance with all such orders.

In similar MEHTA cases, the Supreme Court has ordered the Delhi Administration to relocate nine thousand dirty industries safely away from the crowded capital, to protect the city’s one remaining forest from illegal encroachments, and to build sixteen new sewerage treatment plants. Other MEHTA campaigns have resulted in the compulsory introduction of lead-free gasoline in India’s four largest cities and the prohibition of commercial prawn farms within five hundred meters of the national coastline. In a 1991 ruling, moreover, the Court compelled India’s radio and television stations and movie theaters to disseminate environmental messages daily.

These victories have required years of singleminded exertion. By working eighteen hours a day, MEHTA manages with a tiny staff and the fervent support of his wife and daughter. He work from a cramped office at home and subsidizes environmental cases with fees from his private practice. He faces constant harassment and even threats to his life.

MEHTA’s marathon effort is making legal history. In forty landmark judgments, the Indian Supreme Court has put the stamp of its authority upon his assertion that the “right to life,†as guaranteed in India’s constitution, includes the right to a clean and healthy environment. Furthermore, it has ruled that violators of this right are absolutely liable for the harm they cause. Indian courts may therefore grant compensation to victims of environmental abuse with the certain understanding that “the polluter pays.â€

Fifty-year-old MEHTA keeps his organizational affiliations to a minimum and is known as something of a lone crusader. Still, he devotes several weeks each year to Green Marches, during which he works with grassroots organizations around the country. The movement for a clean habitat must be a people’s movement, he says. “The future lies in the hands of a vigilant public.â€

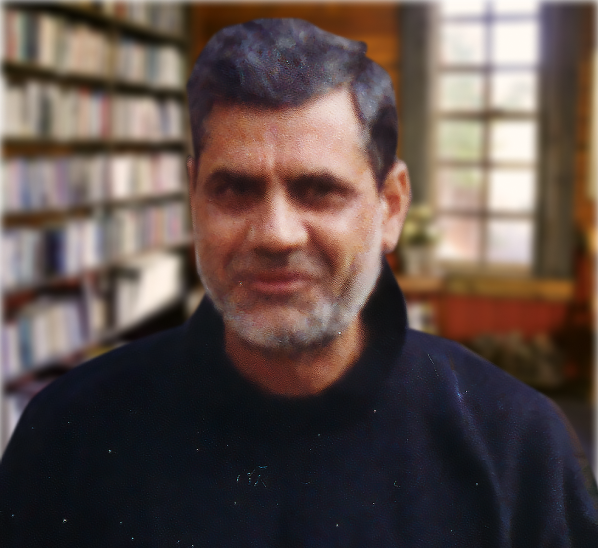

In electing MAHESH CHANDER MEHTA to receive the 1997 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Public Service, the board of trustees recognizes his claiming for India’s present and future citizens their constitutional right to a clean and healthy environment.

This is a moment of great honor for me to be with you today. I would like to share with you on this great occasion some of the thoughts and feelings that coursed through me when I received news of being conferred the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Public Service. One was a feeling of gratitude at the recognition of my struggle to work for the protection of the environment through the legal process. The other feeling that arose in me was of immense satisfaction that the environmental movement in Asia has received great impetus and encouragement.

The need to protect the environment is linked to the very survival of the human race as well as all the other forms of life that coexist with it. Today, the planet is under constant threat form pervasive pollution, pressures of population, poor planning and indiscriminate use of natural resources. Rivers, lakes, coastlines, forests, and the ozone layer have become victims of the depredations of the greedy few, resulting in grave danger to the life and health of a large population in the world.

In the name of development, many Asian countries have become vulnerable to exploitation by the so-called “developed†part of the world. It has been fallacious solution or them to blindly follow the Western model which has overtaxed their natural resources leading to serious socio-economic and environmental consequences. We should not forget that the purpose of development is not to develop material things but develop humankind. Until now, the industrial growth at any cost has been an unchallenged and unquestioned placebo for human welfare. The time has come to do some stock-taking, to look around and see what the consequences of a reckless development are.

There is no other option before us but to seek innovative ways to alleviate our problems without negating the greatness in our cultures and depleting our natural resources. Our traditional wisdom and ways of life provide many viable solutions and alternatives. These need to be examined, revitalized, and incorporated into our planning process.

We must all arise in unison to ace the challenges before us to seek redressal of the present situation. A different mind-set and approach are required to creatively deal with the problems facing Asian nations. The struggle will be a long and hard one, but it promises to bear rich fruit for the future.

Friends, the award, I am sure will go a long way in encouraging and strengthening the environmental movement. I am grateful to the Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation for acknowledging my humble contribution to this cause.