Farmers the world over have much in common that knows no national boundaries. Everywhere they work hard, coaxing the soil to produce, watching the weather and battling a host of enemies from weeds to blight and insects. While officials and technicians meet often in scientific and other gatherings, farmers rarely have the opportunity to trade foreign insight; although their tilling of the land is “first among the arts” it is essentially non-verbal. Dr. NASU recognized this need and acted effectively.

His mother’s love of nature and Tolstoy’s philosophy emphasizing equality of man shaped NASU’s early values. Professor Inazo Nitobe’s commitment to internationalism and better agriculture led his student, born into a Samurai family, to make these his life concerns. Graduated with honors in agriculture from Tokyo Imperial University, in 1914 he joined its faculty. But academic pursuits did not blunt his concern for the feudal inequalities that then stifled Japanese peasantry.

Surveying the plight of islanders in the Marshalls, Carolines and Marianas, NASU recommended policies that helped improve their lot. In the 1920?s, as advisor to the Japanese labor delegation to the League of Nations, he championed the right of tenant farmers to organize. Recognizing early the population and social problems on the land and the need for fair prices for farm products, he became a pioneer in these fields at home and abroad.

After Japan’s defeat in 1945, NASU’s wartime role in establishing a School of Agriculture at Peking University, guiding emigrant settlement in Manchuria and advising the Nanking puppet administration led to his exclusion from government for five years. As a private citizen observing the land reform being engineered by the Allied Occupation, he became concerned that farmers using antiquated methods might still fail to improve their living. Kokusai Noyukai, or the Association for International Collaboration of Farmers, was the solution NASU devised. An agreement signed in 1951 with the Governor of California set the pattern.

At first 30 to 40 young men went annually to California to work for one year with host farmers, learning latest methods for raising rice, fruit, vegetables, flowers, poultry and dairy animals. Others later were sent to Denmark, Holland, Switzerland, West Germany, Canada, Brazil and New Zealand to learn by working and to build enduring ties of friendship. By now some 1,600 trainees have returned to apply their new knowledge of farming, marketing of produce and building cooperatives. On the average, they have almost doubled their family income at home while leading in community betterment. They and their former hosts in Europe and America exchange seeds, fruit trees and even breeding animals. Recently, returned trainees themselves became hosts to a first contingent of young farmers from Korea, Taiwan and Brazil.

When Dr. NASU was appointed Ambassador to India in 1959, he thought again of sharing knowledge. Young Japanese who have established demonstration farms in eight India states include nine trained abroad; the remainder are drawn from the two agricultural training centers for middle and high school graduates established by NASU in 1929 and 1938. In Pakistan, and elsewhere in Asia and Africa, other teams are following this example. Near Agra, Dr. NASU similarly involved his country’s medical profession in creating the India Center of the Japan Leprosy Mission for Asia. At the inauguration he said this effort represented an expression of gratitude for early English and French missionaries who had labored to eradicate leprosy in Japan.

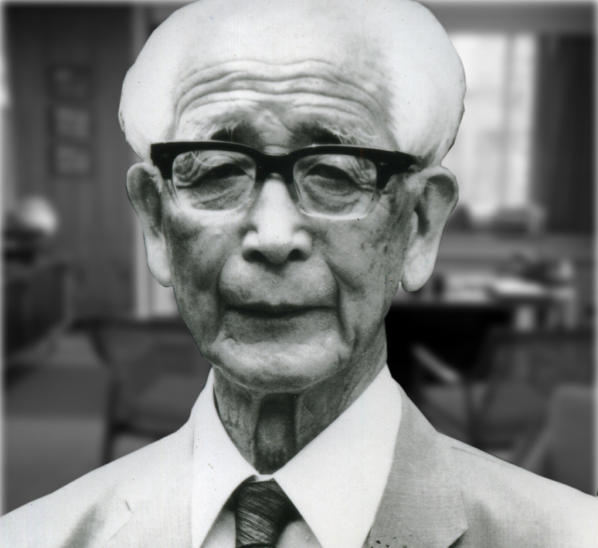

Now 79 years old, Dr. NASU has lived true to his youthful vow: rather than seek personal gain he would devote himself to larger goals benefiting farmers, particularly the least fortunate.

By this election the Board of Trustees recognizes SHIROSHI NASU’s practical humanitarianism, enhancing cooperation in agriculture by learning through multinational experience.

Before expressing my heartfelt thanks for the great honor juts conferred upon me, allow me to make a brief remark in connection with the aim of my humble work, for which the foundation has generously awarded me.

In this troubled world of ours, full of so many grave problems, there loom two towering issues which threaten to bring about terrible calamities, such as the downfall of present civilization or even total extinction of the human race on this planet. One is misuse of nuclear power for destructive purposes; the other is widening disparity between the explosive expansion of world population and the faltering increase of food supply. Here I shall refer to the latter.

The changed world situation revived anew the food and population problem once supposed to have been buried together with the Malthusian Principles. At the World Food Congress held in Washington D.C. three years ago, Professor Arnold Toynbee warned us of the catastrophe which might occur if this problem be not properly met. Today, the Freedom from Hunger Campaign started by FAO (UN Food and Agriculture Organization) is afoot in many parts of the world; but so far, it can not command the sufficient support it deserves.

The satisfactory solution of the problem must come through the full coordination of all concerned: politicians, economic planners, producers as well as consumers of food, medical and social welfare workers, technical experts, educationists, and so forth. When and where national interests collide with international aims, proper adjustment must be made. It is a gigantic work requiring a well-oriented international scheme and tremendous effort.

The significant function of agriculture for increasing food production in this connection can never be overestimated. But, if the regional effort for increased production be carried out without any consideration of similar activities in other parts of the world, the aggregate result can sometimes be quite disastrous. Thus, the so-called “Selected Expansion of Agricultural Produce” was suggested by FAO as a partial remedy some years ago but its actual application up to this day has fallen short of the target.

Perhaps, even a rough sketch of a world agricultural scheme which would meet requirements to solve the food and population problem has not yet been drawn; and even when a scheme emerges, it will be a fluid one ever undergoing changes and modifications. The details of the whole picture are at present very vague. Yet, one thing is clear. That is, in this democratic age the farmers must have their own say in framing the shape and in defining the details of world agriculture in the years to come. They must be allowed to act on their own initiatives. Lacking the full understanding and cooperation of the farming population, no governmental or intra-governmental agricultural policy can hold promise of success.

Farmers all over the world tend to be conservative and their vision is usually limited within their nearest environments. But they cannot remain so in the future. They have to share the burden of creating a new world civilization.

Fortunately, there is no national boundary dividing the mentality and way of thinking of world farmers. In agriculture there is no national trade or technical secret to be hidden from foreign farmers. It is true that there has been international competition in some agricultural products in the past, and this exists more or less even today. But the order of the day is to do away reasonably and fairly with such situations as soon as possible.

Let me add here my humble remark that agriculture is not a mere business, but also a way of life storing much of traditional culture in any nation. The cultural heritage, which encompasses moral and spiritual values of our family or community life, should not be thrown overboard, good and bad alike, without discrimination, even in this fast changing cosmic age. But, in our too much mechanized urban living, we come across such deplorable cases very often. Are not juvenile delinquencies and moral anarchy which haunt so many advanced industrial nations today the sure signs of diseases belonging to the realm of social pathology? Healthy rural civilization can be a sort of cure for these cultural aberrations. John Ruskin once said, “There is no wealth but life.” Enlightened tillers of the soil are called to be internationally united and to march on a cultural crusade of the coming age.

With this and other dreams in mind, I started some 16 years ago a movement in Japan to send her qualified farm youths to the United States and later to some European countries. They lived and worked together with farmers in respective countries. Aside from exchange of technical know-how, it gave them rare opportunities for international understanding and cooperation. When they came back home, some became champions introducing new outlooks and fresh ideas to their own villages. The results were quite remarkable. Others of them went abroad again to help their brethren in developing countries to build up agriculture and to foster food production. Here, the results were also noteworthy. A real beginning was thus made, though much limited as yet in scope. We are looking forward to seeing the emergence of new farmers of the new age, who are competent enough to tackle the difficult food and population problem.

The Ramon Magsaysay Award was set up in memory of your great President whose wonderful character and shining achievements will ever be the source of inspiration for thousands of millions of Asian people.

It is a great honor and privilege for me to have been elected as one of the Awardees this year. Here I must express my most sincere appreciation and gratitude. At the same time, however, I feel that the honor is not exclusively mine. I am receiving the honor because of the admirable efforts of those thousands of young Japanese farmers, and because of the warmest cooperation extended to me by so many good friends at home and abroad. With the fullest appreciation and gratitude to all of them, I receive this wonderful Award in all humility of heart.