National and international efforts to spur Asian agricultural progress have left most ordinary farmers still to participate in the “green revolution.” Their reluctance to do so often does not result from ignorance or time-honored habits. Rather, they are unable to see the new technology as within their reach and compatible with their families economic survival.

Indonesia illustrates the small cultivators’ dilemma. Farm families cultivating one-fourth to two hectares grow more than nine-tenths of all agricultural produce. Yet research, marketing facilities and frequently official priorities emphasize the needs of large commercial estates with more modern management. Bankers also find them a better risk.

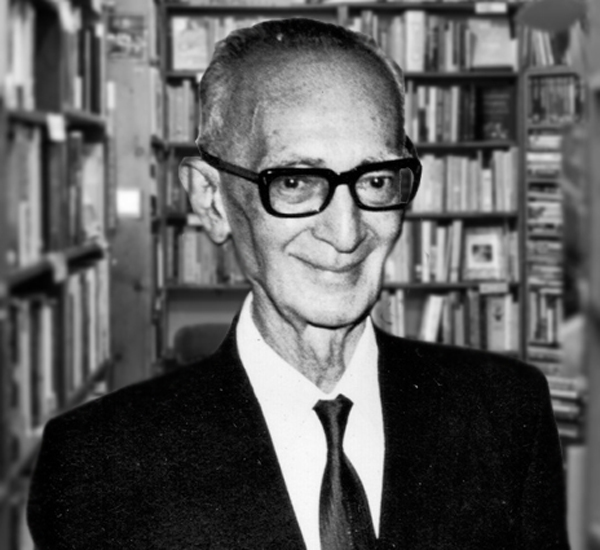

It is to this practical problem that 74-year-old HANS WESTENBERG actively applies himself at Kebun Djeruk—or Orange Plantation—as his 54-hectare farm is known at Tebing Tinggi, some 50 miles southeast of Medan, North Sumatra. Born in this province to a Dutch father and an Indonesian mother of the Karo Batak people, in the family tradition he studied in the Netherlands for the colonial civil service. Attracted instead to agriculture, he returned to Sumatra and in 1919 became a plantation manager. Although concerned chiefly with growing natural rubber, his early success with experimental intercropping on young plantations led him to encourage neighboring small farmers to adopt this practice.

Two decades ago WESTENBERG bought Kebun Djeruk and in 1960 he “retired” there from the state-owned plantation company, Perusahan Negara Penerenpan where he had been employed. Half a century of experience has gone into his experiments since then, nearly all financed with income from the farm.

Convinced that higher-yielding varieties are a “first key” to enhancing farmers’ income, WESTENBERG and cooperating farmers multiplied two and one-half kilograms of the International Rice Research Institute’s first new varieties, IR-8 and IR-5, to produce 800 tons of rice seed which was subsequently introduced by the military throughout Sumatra. Within two years this led to the planting on rainfed fields of a second rice crop worth now some US$10 million annually. He tested 500 types of sorghum and found one from Indiana suitable for Sumatra. Soya bean varieties from Australia, peanuts from Taiwan, corn varieties from Texas and the Super Mungo bean from the Philippines are among his introductions. In fishponds covering six hectares are grown Chinese carp which he sells to restaurants in Medan, while yield records from his fertilized dwarf coconuts promise seedlings for restoring the Indonesian copra industry.

Sumatran farmers who come to learn by seeing the crops that grow best, buy seeds and pamphlets, and students, who live in the Kebun Djeruk ashrama while studying good farming techniques attest to WESTENBERG’s creative influence. Significant is the refusal of this pioneering Indonesian farmer to let fellow farmers buy seeds for a crop unless he has proven it can make money for them. WESTENBERG’s work is a heartening demonstration that private initiative can consequentially increase agricultural production when guided by a deep knowledge of all aspects of farming, a second sense of human nature and sustained personal effort.

In electing HANS WESTENBERG to receive the 1972 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Community Leadership, the Board of Trustees recognizes his practical propagation of new crops and promotion of better methods among Sumatra’s small farmers who have learned to trust and profit from his ideas.

Standing before you as a recipient of the Ramon Magsaysay Award, I am intensely aware of the fact that this is the greatest Award and honor that can be given to a person in Asia. That this Award should be bestowed on me came as one of the biggest surprises of my life. I am overwhelmed with feelings of pride and gratitude.

The question may be asked, and I asked myself many times, what have I done to deserve such a great honor? My personal opinion in this case is that throughout my life circumstances have been very much in my favor and have contributed substantially to the results that have followed from my work. It is thus not that in any way I am worthy of this Award, but rather that circumstances have prospered my activities and focused the attention of many people on the results.

At my birth I inherited a great interest in agriculture from my mother. Then, from the moment I started work on rubber estates in November 1919, I have tried to solve the problems of increasing yields by introducing new varieties and methods of cultivation. This kind of work became my hobby and when one follows his hobby he is in truth simply doing what interests and satisfies him personally; this work, in fact, has proved of no great burden to me.

What one person can do, however, is very limited and it has been my great fortune always to find others who had the same interest or who held important positions in society, willing to cooperate and assist me in the work of introducing new varieties and more advanced methods of cultivation into Indonesian agriculture. In most cases the new varieties and methods we have introduced have been based on the results of recent research carried out by agricultural scientists working in many countries.

By applying the results of basic research, and with the assistance of those in influential positions and others in organizations interested in raising the standard of living of poor farmers, some worthwhile in certain instances substantial results have been obtained through our combined efforts.

Thus, in receiving the Award I feel somewhat guilty, knowing that the Award should have been shared by many others who have assisted my work. I should like to mention a few of these people at this point in recognition of their efforts in supporting my activities:

Our former Indonesian Ambassador to the Philippines, Major General Kusno Utomo, at that time Commander in Chief of the Indonesian Army in Sumatra, provided unstinting support and his Chief of Staff, Major General Josef Muskita, became the head of the project on our experimental farm for the multiplication of the new rice varieties developed in your country. For this operation I was appointed project manager.

Professor Tan Hong Tong, at that time Director of the Research Institute of the Sumatra Planters Association; and R. C. Pickett of Purdue University, who helped me find a suitable variety of sorghum for our region.

The staff of the Rockefeller Foundation and other research institutes who have helped me find high-yielding varieties of corn, soybeans, groundnuts, mungo beans and other crops.

And last but not least, Rudy Ramp, formerly Deputy Director of CARE Indonesia, who played an important role in helping me establish a “Foundation for Indonesian Farming Development.” This Foundation, with the support of influential persons in various ministries of the Indonesian Government and in the business world, will, I hope and trust, continue to improve and extend our work in helping thousands of small farmers improve their economic circumstances.

Perhaps you would like to know what use has been made of the Award money granted me. The money has been fully invested in a project to introduce sorghum into Indonesian agriculture. We have established drying, threshing and marketing facilities to service the small farmers and estates growing sorghum for the first time in our area, and are providing information and supervision, together with credits for fertilizer and seed, to the small farmers involved.

Grain sorghum will surely become a new export crop and an important new basic food grain for domestic consumption because of its high protein content, high yield potential and drought resistance. I believe that it will become one of the most important crops planted by farmers cultivating dryland who have previously had to depend on less reliable crops for their existence.

In conclusion I would like once again to express my gratitude for the honor bestowed on me as recipient of the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Community Leadership and to convey my humble thanks to the Board of Trustees and Members of the Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation for their generosity and hospitality.